From Veronica Mars to Pretty Little Liars

So, Pretty Little Liars has become my most recent obsession. It’s partly that combination of recognition and nostalgia that makes me proclaim “It’s like Roswell’s spirit infused into Veronica Mars’ driving serial storyline, dressed up in Gossip Girl’s clothes.” Indeed, crucial to my experience of a show like Pretty Little Liars is the running comparative commentary in my head, based on my personal preferences and viewing history of teen-now-millennial television.

So, Pretty Little Liars has become my most recent obsession. It’s partly that combination of recognition and nostalgia that makes me proclaim “It’s like Roswell’s spirit infused into Veronica Mars’ driving serial storyline, dressed up in Gossip Girl’s clothes.” Indeed, crucial to my experience of a show like Pretty Little Liars is the running comparative commentary in my head, based on my personal preferences and viewing history of teen-now-millennial television.

Today, I’d like to consider the way in which the series revisits and revises some of the key themes that made Veronica Mars so compelling, and merges them with Gossip Girl’s vision of the power of the socially-networked millennial generation. Channeling Veronica Mars we have the themes of male power and female vulnerability; female strength and male disconnectedness; the strength of millennial networks (in this case—and in contrast to Veronica Mars—mostly female networks); and the fascinatingly repeated trope of the dead, sexually-promiscuous girl at the center of the mystery, who haunts the narrative in potent flashback.

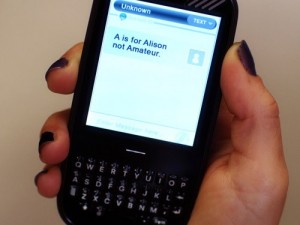

In Pretty Little Liars, this dead-but-still-powerful girl is Alison, the ruler of the main characters’ social clique, who was found dead after an outdoor sleepover with her friends. In the series’ opening episode, the main characters (Aria, Spencer, Hanna, and Emily) begin to receive terrorizing texts from a mysterious “A” who seems to somehow possess Alison’s intimate knowledge of their secret lives. Alison thus doubly permeates the narrative, both in color-saturated flashback a la Veronica Mars and in disembodied text message, email, etc.

Where have we come from Veronica Mars’ Lily to Pretty Little Liars’ Alison? In Veronica Mars there was a sense that Lily had power beyond the grave to draw everyone into her mystery, culminating in Veronica locked in a fridge begging to be saved (one of the most disappointing moments of TV I can recall), rescued from death only by her father. Lily even in death was still a deeply powerful character, and revealed to be even more so with each twist to the mystery. In Pretty Little Liars we have Alison, similarly a sexually direct teenage girl, and a social power player when she was alive. Now dead, her digital extension “A” seemingly rules the characters from beyond the grave, through the millennial tools of social networking and mobile technology. She commands her once peers via text command, email, and video attachment.

Alison’s digital manifestation is reinforced by her fluid and inexplicable power-through-knowledge; she seems to somehow see everything, know all, and could potentially be anyone. Indeed, if A/Alison has a counterpart in currently airing teen TV programming, it would be the anonymous and all-seeing Gossip Girl. Like Gossip Girl, A could be old or young, male or female, one or many. However, the difference in the characters’ assumptions about A vs. Gossip Girl are worth noting: the teens of Gossip Girl assume their anonymous blogger to be young and female, the teens of Pretty Little Liars assume A to be older and male. In a sense, A merges the power wielded in Veronica Mars (of those already in power—older, male, wealthy, white) with the power wielded in Gossip Girl (decentered, anonymous, socially-networked).

Veronica Mars offered a targeted attack against the systems of power, with millennial social networks used as grass roots organizing to take down those in power. In contrast, in Pretty Little Liars power threats potentially come from within, and even if the murderer turns out to be the older male Ian (more likely he’s a red herring), he’s a) not that much older, still quite arguably a millennial and b) essentially part of one of the main character’s family. But it seems more likely that A will turn out to be, if not Alison herself, one of the seemingly side-lined teen or post-teen characters who populate the margins and sometimes center of the text. Another way of thinking of this, in terms of Veronica Mars, is that Lily’s murderer and Veronica’s rapist become one; those in power are no longer pulling strings from behind the walls of corporate business, but rather reside in the family, in the network, using the same millennial tools as the main characters to punish and control.

A recent episode included a shout out to Veronica Mars that at first seems almost trite but actually I find quite fascinating. When Spencer indicates that they “need to find some kind of proof” to implicate the older male A suspect, Hanna replies sarcastically, “Thank you, Veronica Mars.” An homage, yes, but the sarcasm suggests that the impetus laid on Veronica to fight the system is somehow already assumed, doesn’t need to be spelled out, and has been dispersed among all of the young female characters rather than residing primarily in one heroic figure. I’m torn about this, because on the one hand I am coming to appreciate the way in which Pretty Little Liars offers a robust sense of the multiplicity of young female experience, empowering without idealizing multiple young women who face different challenges. On the other hand, I worry for the series’ depoliticization of gendered violence as the show’s narrative obscures systemic inequities. But most of all, I hope that Pretty Little Liars won’t resort to that single, intensely disappointing moment where our young female heroes need to be saved rather than figuring out how to save each other.

Great post, Louisa — and I have little to add save you’ve definitely convinced me to watch (and compare)…..

Glad to hear I’ve inspired you to give it a try! I would say that if it doesn’t grab you at first, do keep watching. It took me a couple of tries to realize that it was worth sticking with. And I’d love to hear your comparisons once you’ve dug in!

Interesting post Louisa, though I do shudder at the aligning of the show with my beloved VM. I tried hard with PLL, but due to a lack of time it ultimately lost out in my affections to Make It or Break It, (the battle of the UK imports of ABC Family shows!) which I preferred for its female representations. I love a bit of teen camp – and i’d enjoyed the lead actress in Privileged – and i’d originally positioned PLL as my replacement for One Tree Hill (which lost steam in last season for me), but I think that my ultimate problem with it came down to both production factors. The actresses playing high school friends had such an obvious range of ages it just got in the way of my submitting to its world, with at least one looking mid-20s (plus, Kendra from Buffy still playing a high school student many many years later). Additionally, I got a bit squicked out by the teacher/student romance. You present an interesting read of the networked world of the teen girl though – which at least in the UK is expanded out into the marketing and trailers of PLL.

Hi Faye–Thanks very much for commenting! In full disclosure, I actually gave up on PLL during my first attempt, and only came back to it very recently, initially skipping a few and thus realizing that it is (thankfully) much more a serial mystery than an episodic teen show with a few serial tendencies. I’ve been thinking recently about how different viewers have their different litmus tests: for you it sounds like it’s about believability and tied to both production value and actor age, for me I’m perfectly happy to suspend disbelief re: character ages (actually, I’m pretty much primed to do so now!) if the plot has enough serial complexity & mystery.

I’m also quite fascinated by the trend toward teacher/student romance; there are currently three (count them, three!) currently-airing TV shows featuring teacher/student romance. Gossip Girl even went out of its way to retrofit a teacher/student romance into its primary mythos.

I’d love to hear about the UK marketing and trailers that are emphasizing the networked teen girl aspect!

Yes, the TV critic Dan Feinberg was pointing up the squicky statutory rape elements of PLL and Life Unexpected – with the showrunners of PLL i believe calling it a ‘statutory romance’ in response to questions at critics tour. Particularly when you link it in with the ‘teacher as rapist’ storyline of 90210. I’m normally fine with older actor ages (we discussed this in my teaching the other day actually), but its when it’s such an outlier in relation to the ensemble – say Teddy in 90210 – as in PLL that it pushes me out.

The trailers that run on Viva (our free-to-air MTV spin off station) for PLL are a bit confusing to me in their context – they are in the pink and green/yello branding of VIva – and are a series of whispered read outs of onscreen status messages in US accents in the vein of ‘OMG, can you believe what’s happening’. I’ve always assumed these were US ones grafted in, as the dates of the status don’t match the UK airings and its general promos are -as a sexy older lady – a rare US ‘voice’ on Viva, which usually goes for E4 rip-off blustery male style VOs.

It seems to me like you resolve your disappointment with VM in your final sentence here: the crucial difference between the two shows, as you note, is that PLL doesn’t concentrate all of its heroism into a single character. The various female leads can save each other and it remains empowering, while still narratively realistic. Conversely, on VM, Veronica was resourceful and saved herself regularly — to think that she’d be able to it time after time is implausible and narratively unsatisfying (honestly, would Veronica finding a way out of the fridge on her own have been any *less* disappointing?). The only difference is that, because Veronica was the only female protagonist (until Mac became a regular, at least), her rescue had to be effected by a man. On PLL, the reality of occasionally needing help — as any human being does — can be balanced with the political ideal of female empowerment simply because there are more women participating in the narrative.

As wonderful a show as VM was, there was a lot of exceptionalism built into the strong female role at its center. Although PLL is wrapped in more conventional trappings, it’s arguably more subversive in presenting multiple female protagonists, such that female agency can be more broadly asserted. (If we’re comparing seminal female-centered teen shows, it’s kind of like how Buffy shared her power with all the potential Slayers! That was awesome.)

You get right to the heart of it here!:

Although PLL is wrapped in more conventional trappings, it’s arguably more subversive in presenting multiple female protagonists, such that female agency can be more broadly asserted.

That’s absolutely what I think is going on, and I’m fascinated by how PLL is wrapped in these conventional trappings (although still connected to a noir-like mystery about sexual violence…) and yet still potentially quite subversive, arguably (dare I say it?) more so than Buffy and VM. Buffy shared her power with the potential slayers only at the very end of the series, as an act of closure, shifting the series from its predominant focus on female empowerment as exceptionalism to a more collective sense of female power that the series could imagine but not depict long term–PLL uses that female network as its starting point.

I don’t mean at all to undermine or oversimplify VM and Buffy, two shows that I love dearly. But I do feel that because of PLL’s conventional trappings (as you so rightly put it) the series’ place in this trajectory of 3rd wave feminist shows could be overlooked.

Thanks for commenting!

I actually never thought of the refrigerator as a thing where she “has to be saved by a man”. I always read that scene as a harsh reminder that, despite all the awesome that Veronica possesses, she’s still just a tiny little teenager. I always loved that scene because she seems truly vulnerable and even though it is television, there is a real sense of danger and potential death. Kristin Bell sells it hardcore.

I can see your point, but I didn’t interpret it as a man/woman thing. I saw it as a child/adult thing.