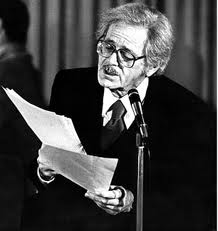

On Norman Corwin, Poet Laureate of American Radio

Norman Corwin passed away last month, at the ripe age of 101. Though his death prompted praise-filled obituaries in prominent places, one suspects that the number of people younger than 60 whose eyes were caught by the headlines was miniscule. I happen to be teaching a course in Radio and the Art of Sound this semester, in which Corwin’s work has figured large, and I was glad to have added 25 people under the age of 30 to the ranks of those who noticed. This is not to belittle Corwin’s towering accomplishments in the early period of radio sound experimentation: for two decades, he was indeed American radio’s poet laureate. So why does his name evoke so little recognition these days, even from people interested in broadcasting history?

Norman Corwin passed away last month, at the ripe age of 101. Though his death prompted praise-filled obituaries in prominent places, one suspects that the number of people younger than 60 whose eyes were caught by the headlines was miniscule. I happen to be teaching a course in Radio and the Art of Sound this semester, in which Corwin’s work has figured large, and I was glad to have added 25 people under the age of 30 to the ranks of those who noticed. This is not to belittle Corwin’s towering accomplishments in the early period of radio sound experimentation: for two decades, he was indeed American radio’s poet laureate. So why does his name evoke so little recognition these days, even from people interested in broadcasting history?

The answer, I believe, lies partly in the qualities of Corwin’s work, partly in the vagaries of broadcast history. As with many other innovators in the field of radio production, as well as in radio research, the propagandistic fervor of World War II swept Corwin up into its too-hot embrace (to reference Mr. McLuhan) and led the emerging art of radio feature production into a too-close alliance with god and country and self-righteous patriotism. Corwin’s two best-remembered works are We Hold These Truths, the nation-wide broadcast carried by all three networks on the brink of war (December 15, 1941), and On a Note of Triumph, his 1945 paen to Allied victory. Both are virtuoso examples of Corwin’s “kaleidosonic” technique (thank you Neil Verma), swooping from omniscent narrator to scenes of battle to church choirs to folksongs to dramatic dialogues to set speeches, underscored with bombastic music and pushing us to ever greater heights of patriotic self-congratulation with a now embarrassing lack of irony or restraint. Corwin was anything but cool.

Another problem is that Corwin’s reputation, boosted by government-sponsored programs during the war, has eclipsed the larger tradition of US feature production, much better understood and perpetuated in Britain and Europe. The radio feature represented the most creative aspect of sonic innovation in radio for decades, firmly established in the BBC where a Features Department nurtured the careers of producers like D. G. Bridson, Marjorie Banks, Nesta Pain, Charles Parker, and Ewan McCall. Corwin worked with some of these artists during the war, and his series An American in England, produced with the help of Edward R. Murrow and his CBS news team, with original scores by Benjamin Britten, remains among his best work, in my opinion.

Another problem is that Corwin’s reputation, boosted by government-sponsored programs during the war, has eclipsed the larger tradition of US feature production, much better understood and perpetuated in Britain and Europe. The radio feature represented the most creative aspect of sonic innovation in radio for decades, firmly established in the BBC where a Features Department nurtured the careers of producers like D. G. Bridson, Marjorie Banks, Nesta Pain, Charles Parker, and Ewan McCall. Corwin worked with some of these artists during the war, and his series An American in England, produced with the help of Edward R. Murrow and his CBS news team, with original scores by Benjamin Britten, remains among his best work, in my opinion.

Now that we have entered a “second golden age” of the radio feature, with work such as Ira Glass’s This American Life, the sound experiments of Jad Adumrad and Robert Krulwich’s Radiolab, and organizations like the Third Coast International Audio Festival bringing it all together, perhaps Corwin can be remembered again for what he contributed to sound form and style. A few new books seem to indicate this: Michael Keith and Mary Ann Watson’s publication of Corwin’s diary from his epic post-war work One World Flight, Matthew Ehrlich’s Radio Utopia on the post-war radio documentary, and Neil Verma’s forthcoming Theater of the Mind. Norman Corwin lived just long enough to see this period emerging. I hope it made up for the decades of neglect.

Thanks, Michele, for pointing this out. I just played a snippet of “We Hold These Truths” for a course on American Culture in the 1930s-40s. I must confess, with some shame, that I used it as an example of didactic radio propaganda in contrast to propaganda integrated into entertainment (as in the Gracie Allen bit in the NBC Mileage Rationing Special). My students preferred their war propaganda couched in comedy, of course. So your point that Corwin’s legacy is partly obscured because of that association with bombastic war propaganda is well taken! I plead guilty to perpetuating it–though I did tell my students that I was being unfair to Corwin by using that as the only example of his work!

Thanks for the mention, Michele! I’m delighted to hear that you’ve been teaching these plays. Even when they’re vastly embarrassing, they have a kind of richness. I agree completely with your thoughts above on why Corwin sounds so alien to us today, and with your praise for the American in England series. I’ve been rereading notes from my interviews with Norman since he passed. At one point he said that he thought the “Cromer” episode was one of his best works ever. Also that the This is War series (surely the “hottest”) were the worst. That sounds about right to me.

Best, nv