The GSU Copyright Case: Lessons Learned [Part One]

Some of you may have heard that this week a Georgia judge issued a long-awaited legal decision in a case entitled Cambridge University Press v Mark P. Becker. If you haven’t paid attention to it before, it is important to read up on it now, as the ruling impacts each and every academic and student.

In case you haven’t been following the suit, here’s a quick summary: In 2008, three academic publishers (Oxford, Cambridge, and Sage) filed suit against Georgia State University [GSU] for copyright infringement. At issue was how instructors were using the library’s E-Reserve system—a password-protected site that offered for students scanned copies of chapters from books and journal articles from reading lists for individual courses. After a three-week trial in May 2011 and one year of deliberation, Judge Orinda Evans found GSU guilty of five cases of copyright infringement. That may sound like a loss but in fact GSU was not considered liable or viewed as acting within the bounds of Fair Use for 94 other alleged infringements.[1] You can read the decision here and there are already a few legal interpretations of the decision offered online here and here. There is certain to be more legal analyses of this decision because its implications for broader academic and pedagogical practices may be significant.

In general, there seems to be reason for GSU and other universities to pop the cork on some champagne—the limited “wins” for the plaintiff have likely made future cases of this type more trouble than they are worth. The wider implications of the case, however, are more concerning.

I should note up front that I am not a law student. I’m a media studies doctoral candidate with an interest in policy. Nothing I write here carries with it the authority of a legal degree. Instead, I offer an experiential discourse because I provided a deposition for this trial. I’d really love this post to be a detailed discussion of the deposition process, because I found it fascinating, but as this case will likely continue on appeal, I don’t want to implicate myself further. This concern—my worry of implicating myself—is what I’d like to focus on for the rest of this piece, offered in two parts, sharing a few lessons learned.

Lesson 1: Universities and departments have a responsibility to educate faculty and student teachers about Fair Use and official policy regarding copyright.

Even as we worry that libraries are losing their role as community centers of learning and gathering, Fair Use has infused many of these sites with a new mission. The GSU legal team advanced an argument that our use of digital materials on E-Reserve equaled the placing of hard copies of a book chapter owned by the library on a tangible reserve list. This argument seems persuasive to me, but it demonstrates the thorny issues involved in digitally reproducing materials for instructional purposes. The fact that faculty use of library resources formed the heart of this case should not be read as a validation of similar use of uLearn (formerly Blackboard) and personal faculty websites. Any time teachers upload copyrighted material to a website without adequate attention to Fair Use, they are potentially liable for copyright infringement.[2]

My favorite tidbit about this case is that one dispute between the plaintiff and the defendant centered on the question of what qualifies as a book or work in a Fair Use claim. The plaintiff argued that any numerical interpretation of Fair Use should not include in the page count the table of contents, figures, index, or footnotes. For example, a common perception of Fair Use posits that use of 10% of a book, when that 10% does not constitute the “heart of the work,” may be Fair Use. The 10% here must be calculated against the page total of the chapters only. This struggle over semantics indicates the intricacies involved in understanding the constantly evolving case law of copyright and Fair Use, underscoring the urgent need for a common set of practices across academia, or at least within disciplines.[3] As the GSU case documents, many professors do not share a common understanding of how our university defines Fair Use. Education of our educators is essential.

In the comments, please feel free to offer ideas for how universities can better address the challenges of copyright and Fair Use. Did your pedagogy course address these topics? Does your university host mandatory continuing learning sessions about Fair Use and university policy? Do you partner with an organization that advocates for Fair Use?

In part two of this post, I will address lessons for individual scholars and teachers.

[1] Only 79 of the original 99 alleged instances of copyright infringement went to trial. For example, my own case seems to have been eliminated due to confusion about rights ownership.

[2] The judge’s decision took some time because she reviewed each individual instance of alleged infringement, assessing each one in turn in the decision. Consider reviewing these instances in the decision to compare their use of E-Reserves to your own use of web-based course materials.

That 10% question is the worst thing to come out of this case. Previously, 10% was a rough guideline that the Copyright Office suggested, but I could still argue with my library that, say, 12% of the book (e.g. a 24-page chapter in a 200-page book) was still reasonable and fair. Fair use should flexibly accommodate the sensible subdivision of a larger work.

Now, thanks to the judge’s attention to and emphasis on that 10% figure, universities around the country are going to dogmatically adopt that as THE LIMIT beyond which they can’t go without risking a lawsuit, meaning that a lot of work is going to be licensed just because it is a couple of pages over some arbitrary (and frankly stupid) mathematical limit.

The judge also all but begged the copyright holders to establish a thriving market in licenses so that the fourth fair use test (effect on the market) will work in their favor.

That makes the winner here CCC, the organization that purports to represent copyright holders and that runs something of a licensing racket against universities. Between this ruling and the Access Copyright deals in Canada, the pressure is on universities to play it safe within rules that favor the increasing corporatization and monetization of the education system.

In other words, only the copyright holders most egregious overreaching was refuted here. That makes this case a fair-use “victory” that, in practical consequence, will mostly prove worse for educators and further concretize the mindset of “permission must always be requested and everything must always be paid for” both in academe and in the culture at large.

Thanks for your post–I’m looking forward to part 2.

Chime!

What is particularly galling is that these academic publishers are trying to force educators to *pay* for using academic work that was produced by educators, edited by educators, and disseminated by educators (assigning a reading is a form of free marketing!), all without direct payment from the publishers.

Academic publishers have a market problem, no doubt (small markets for majority of academic work), but their business model is not only exploitative but reliant on taxpayer-subsidized educational institutions to pay outrageous access fees for material those institutions’ employees have produced.

Relying on copyright law to forcibly create a market may prove, in the long run, to undermine the very market for academic work that these publishers think they are protecting. I, for one, no longer use services like E-reserve, and I’m sure I won’t be the only one looking for work arounds.

Cynthia, I touch the issue of labor exploitation in the next post, so thank you for bringing it up here. There are all sorts of strange ironies with this very small community. The instance of alleged copyright infringement for my own circumstance involved one essay from an anthology edited by a member of my dissertation committee. Often when we use work in a class, we have met the authors and talked with the press representative in the very friendly setting of the conference exhibition hall. Having this matter settled in a court room obscures all of those connections and relationships.

What are the reasonable digital alternatives to E-reserves for course materials? The fact that the library played a prominent role in this case provided professors with some protection, in my view. Use of a personal website would provide none of that. Are you referring to sites like Critical Commons–have you used them to build a reading list for a course?

Look forward to post #2!

Confession: I use fewer academic articles in my undergrad classes, mostly because my students’ reading comprehension is so poor. More and more I use links to quality journalism and media artifacts and trade sites as course materials students must analyze and write about. But that begs your question. Graduate courses need vast amounts of academic articles.

I wonder if instead of posting things through the university library, posting things on independent sites might actually be safer? Publishers can target universities, but how many of them pursue individual infringement cases for PDFs posted on a password-protected Google Site page, for instance? Does anybody know of cases?

No, there is no guaranteed work around. Whether I hand out hard copies, individually copied to avoid fees at the copy shop, or post PDFs I’ve scanned on password protected sites, or just link to other material, I am going to continue to try to avoid playing by these rules.

Thanks for the comment, Bill. One of the things I’ve been pondering is whether this will influence the popularity of anthology publications. The point of an anthology is to offer a variety of perspectives on a topic, which often makes them ideal for classroom use. But with a 10% limitation on Fair Use, the anthology may provide one essay only for classroom use–hardly the intended multiplicity.

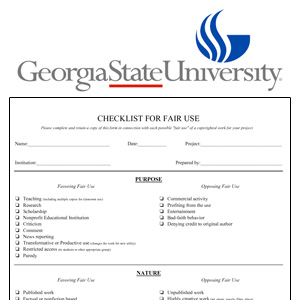

I agree with you that any hardening of the terms of Fair Use may prove problematic. Checklists like the one shown here intend to simplify, but the binaries offered are rarely clear cut. It works to the advantage of publishers to establish hard lines, regardless of context or intent.

[…] Part One is here. […]

[…] The GSU Copyright Case: Lessons Learned [Part One], Karen Petruska, Antenna. [Petruska is a GSU graduate student who was deposed] […]