A Reflection on Rodney King and the Poignancy of Satire

“King was found dead in his swimming pool, and police say it appears to be a drowning with no signs of foul play,” reported Allison Keyes on June 17th, and I turned up my car stereo. I hadn’t thought about Rodney King in ages–probably not since the Los Angeles Uprising subsided twenty years ago. In 1992, King was brutally beaten at the hands of several L.A.P.D. officers, an incident that made national headlines thanks to George Holliday’s videotape of the altercation. When three of the officers were acquitted of brutality charges (the jury failed to reach a verdict on the fourth), L.A. erupted in a week-long race riot that resulted in 53 deaths, over 2,000 injuries, and $1 billion worth of damage to the city. And as the city burned around him, King earnestly uttered one of the most famous questions of the 1990s, “Can we–can we all get along?”

“King was found dead in his swimming pool, and police say it appears to be a drowning with no signs of foul play,” reported Allison Keyes on June 17th, and I turned up my car stereo. I hadn’t thought about Rodney King in ages–probably not since the Los Angeles Uprising subsided twenty years ago. In 1992, King was brutally beaten at the hands of several L.A.P.D. officers, an incident that made national headlines thanks to George Holliday’s videotape of the altercation. When three of the officers were acquitted of brutality charges (the jury failed to reach a verdict on the fourth), L.A. erupted in a week-long race riot that resulted in 53 deaths, over 2,000 injuries, and $1 billion worth of damage to the city. And as the city burned around him, King earnestly uttered one of the most famous questions of the 1990s, “Can we–can we all get along?”

More than the man himself, King’s plea for peace became a symbol of tense times, wrenched from the shaking man’s lips to frame him as an unwitting cultural icon. So I wasn’t surprised that this line, often misquoted “Can’t we all just get along,” sprung to my mind when I heard King’s NPR obituary. What did surprise me, though, was the image in my mind’s eye. It wasn’t King at all–it was David Alan Grier. And it wasn’t a news broadcast–it was In Living Color.

In Living Color, set to be “rebooted” next spring, was the comic brainchild of Keenan Ivory and Damon Wayans. In its heyday, the award-winning mixed-race sketch comedy series catapulted then-unknowns like Jamie Foxx and Jim Carrey to stardom, and its revolutionary take on 1990s culture earned the series TV Land’s Groundbreaking Award. The series’ knack for racial commentary and its Hollywood headquarters made it an obvious venue for a satirical take on the Los Angeles Uprising, and the show’s 1992 season overflowed with dancing looters, L.A.P.D. Sgt. Stacey Koon’s exaggerated lisp, and of course, David Alan Grier as Rodney King.

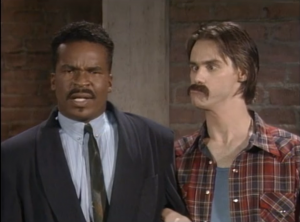

In a particularly memorable sketch, Grier’s Rodney King is joined by Jim Carrey’s Reginald Denny, the truck driver pulled from his cab and beaten nearly to death in the rioting. Grier’s dialogue, peppered with clichés like those in King’s famous address, urges viewers to “Stay in your car!” Grier’s face twitches uncomfortably and Carrey’s eyes look in opposite directions, dark reminders of the violence that left King with permanent brain damage and Denny with a dislocated eye socket, among numerous other injuries. The scene ends as the two shuffle anxiously over to a brown Hyundai, reminiscent of King’s vehicle on that fateful night. The sketch is the kind of funny that puts a knot in your stomach. In 1992, it provoked the kind of laugh that moved that lump out of your throat for just a minute–it was comic relief in every sense of the phrase.

Satire is an amazing thing. It has a way of softening and recasting difficult subjects; it makes the really tough cultural stuff palatable enough  to consume and digest. Rodney King’s face, twisted with pain and anxiety, was heart-breaking; David Alan Grier’s was poignant and irreverently reflective. It provided enough distance to allow for a thoughtful consideration of the moment’s haunting urgency. In Living Color was easier to watch than the surreal footage of people bleeding to death on the streets of a burning American city, and Grier’s comically twitching eye wasn’t as emotionally crushing as King’s plea for peace. America needed both. And for some of us distanced both proximally and culturally from the Uprising, the parody not only made sense through our understanding of the real–the real made sense through the lens of the parody. This complex interplay fused together my memory of the comic signifier and the tragic signified forever.

to consume and digest. Rodney King’s face, twisted with pain and anxiety, was heart-breaking; David Alan Grier’s was poignant and irreverently reflective. It provided enough distance to allow for a thoughtful consideration of the moment’s haunting urgency. In Living Color was easier to watch than the surreal footage of people bleeding to death on the streets of a burning American city, and Grier’s comically twitching eye wasn’t as emotionally crushing as King’s plea for peace. America needed both. And for some of us distanced both proximally and culturally from the Uprising, the parody not only made sense through our understanding of the real–the real made sense through the lens of the parody. This complex interplay fused together my memory of the comic signifier and the tragic signified forever.

The L.A.P.D. didn’t kill Rodney King on that fateful night. Instead, their TASERS and night sticks, aided by a camcorder and the American media, solidified his place in our cultural memory. And while that space may have been co-opted and renegotiated by comic satire, the cool thing about media is that it leaves all kinds of trails–nothing is ever really lost. So after I finished listening to the NPR story about King’s death, I Googled David Alan Grier’s impression, taking in two very different mediated projections of an icon unwittingly thrust into the heart of a war.

But to the real man, the late Rodney King, attention must be paid. So I pulled up a YouTube video of King’s famous statement, the original one, in all of its pained, horrified, prolific glory, and I did my best to pick apart the man from the parody. After all, the least I can do is accurately remember, in King’s own voice, the movingly genuine phrase he wanted to be remembered by: “Can we all just get along?”