The Real Housewives of (the “New”) Miami

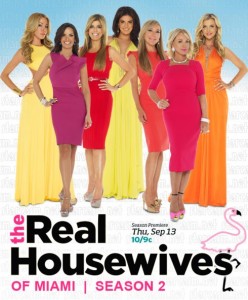

After a truncated first season, and an unofficial cancellation, the Real Housewives of Miami (RHOM) returned last week to “spice up” the Bravo network. Unsurprisingly deploying the ethnicized rhetoric of Latina/o sexiness, the show was resurrected with a seemingly explicit intention of introducing a new “flavor” to the network’s exceedingly successful, yet utterly formulaic, Real Housewives franchise. However, while clearly trading on the legacy of representation that frames Latina/os as “spicy” (a marketing strategy that has been extensively discussed by scholars such as Angharad Valdivia, Arlene Dávila, Mary Beltrán, and Isabel Molina-Guzmán) the RHOM simultaneously constructs a shift in the racialized character of the city itself.

After a truncated first season, and an unofficial cancellation, the Real Housewives of Miami (RHOM) returned last week to “spice up” the Bravo network. Unsurprisingly deploying the ethnicized rhetoric of Latina/o sexiness, the show was resurrected with a seemingly explicit intention of introducing a new “flavor” to the network’s exceedingly successful, yet utterly formulaic, Real Housewives franchise. However, while clearly trading on the legacy of representation that frames Latina/os as “spicy” (a marketing strategy that has been extensively discussed by scholars such as Angharad Valdivia, Arlene Dávila, Mary Beltrán, and Isabel Molina-Guzmán) the RHOM simultaneously constructs a shift in the racialized character of the city itself.

Replacing over half of the original cast, the second season seems to be attempting to reflect a more diverse sampling of the city’s residents. Situated within the discourses of class and excessive wealth, the show’s new cast members claim that Miami is changing. What is not said, but clearly implied, is that Miami’s transition from “Old” to “New” is one not necessarily marked by wealth—new versus old money—as the cast members might suggest, but one that is instead marked by a process of whitening. The “New” Miami is a white Miami, one that can capitalize on the extracted elements of Cuban culture when it so desires, but one that is ultimately laboring to disassociate itself from the racialized baggage of the “Old” Miami.

I am not denying the association of Cubanness with notions of whiteness that played a critical role in the form and fashion of representational Cuban latinidad—a reality reflected in Mary Beltrán’s analysis of Desi Arnaz as ethnically Latino but racially white (Latina/o Stars in U.S. Eyes 2009). What I am suggesting, is that even though the usage of racialized or ethnicized signifiers is abundant in RHOM—much in the same way the franchise’s Atlanta cast is racially marked (see Kristen Warner)—it nevertheless uses those signifiers to assert the city’s movement away from its Cuban heritage. Best represented in the image and rhetoric of the show’s most famous new cast member, supermodel Joanna Krupa, the beautiful people of Miami are being replaced not by a new generation of Latina/os, but by those who better adhere to normative white standards of beauty and don’t stand for, what Krupa called in her Bravo blog, any of Miami’s “nonsense.”

I would argue that the articulation of a “New” Miami by the new cast members of RHOM is an effort to normalize and racially separate themselves from the eccentric latinidad of “Old” Miami, one that is epitomized by the show’s breakout figure: Mama Elsa. The mother of one of the show’s three remaining original cast members and one of the most talked about secondary figures from the entire franchise, Mama Elsa is a woman from the “Old” Miami. She is not only disfigured by extensive plastic surgery, but is positioned within the representation of the Latina witch (a figure that might be lesser known than other Latina representations, but one that nonetheless has a long history in U.S.-based mediated constructions of latinidad that often manifests in the “superstitious” abuela, or the Caribbean santera, or the elderly woman in the village who has held onto the old indigenous ways). At the end of the first episode, Mama Elsa, in describing Miami, suggests that people like Miami not because it is a great place, but because it is an odd place. And it would seem that no one knows that more intimately than the psychic, dramatic, and overly expressive Mama Elsa.

I would argue that the articulation of a “New” Miami by the new cast members of RHOM is an effort to normalize and racially separate themselves from the eccentric latinidad of “Old” Miami, one that is epitomized by the show’s breakout figure: Mama Elsa. The mother of one of the show’s three remaining original cast members and one of the most talked about secondary figures from the entire franchise, Mama Elsa is a woman from the “Old” Miami. She is not only disfigured by extensive plastic surgery, but is positioned within the representation of the Latina witch (a figure that might be lesser known than other Latina representations, but one that nonetheless has a long history in U.S.-based mediated constructions of latinidad that often manifests in the “superstitious” abuela, or the Caribbean santera, or the elderly woman in the village who has held onto the old indigenous ways). At the end of the first episode, Mama Elsa, in describing Miami, suggests that people like Miami not because it is a great place, but because it is an odd place. And it would seem that no one knows that more intimately than the psychic, dramatic, and overly expressive Mama Elsa.

Diane Negra’s scholarship on ethnicity and female stardom provides an approach to a concurrent and contradictory distancing and appropriation of Cubanness in RHOM. Negra contends that “In a large part, the ethnic female body serves as a repository for fears of difference that play out across several registers, activating anxieties pertaining to femininity, to ‘foreign’ ethnicities, even to the uncontrollable, lower-class body” (Off-White Hollywood, 2001: 19). What is important here is that ethnic female stars, as both personae and texts, reflect and contribute to the labor of articulating and maintaining the boundaries of American whiteness. The ethnic female star, as one that transgresses many of the normative boundaries of whiteness, threatens to reveal the “fragile construction” of white, American patriarchy and therefore it must be neutralized. Furthermore, Negra contends that intimately tied to such processes are the discourses that construct ethnic femininity as excessive and exaggerated—in a very embodied way. By offering figures seen as clearly binary oppositional (Mama Elsa and Joanna Krupa) and deploying a ubiquitous framework of “New” versus “Old,” RHOM demonstrates the excessive ethnicity of the “Old” Miami and subsequently reinforces boundaries of whiteness.

Latina bodies are explicitly both ethnically/racially and sexually marked in such a way that they can be consumed, commodified, and exploited, and the RHOM is in many ways no different from the litany of media texts that exhibit this practice. Yet this is a shallow assessment of what is actually unfolding in the show’s representation of a transforming Miami identity. When one delves deeper, what is revealed is how ethnicized Latina bodies are participating in the “processes of ethnic retention, invention and resuscitation” that contribute to both the maintenance and assault on normative boundaries of U.S. whiteness (Negra 2001: 24). I am in no way suggesting that the show’s intention is to reflect the hegemonic struggle over constructions of whiteness, however, that seems to be the result of Bravo’s re-casting of the initially abandoned Real Housewives of Miami.

Keara,

This article abounds with insight. Thank you for sharing such deep analysis of a complex subject matter. What do you make of Leah’s relationship and interaction with the Afro-Latina Freda (“Fredita”), her maid? According to Leah, Freda “cleans when she wants to, answers the phone when she wants to, speaks English when she wants to, and listens to Spanish talk radio 24/7 until I unplug the radio.” But she’s “loyal”.

I’d also like to know what you think of the placement of the “Latin Lover” soap star boyfriend who is at the center of the drama between two professionally successful (and seemingly independent) women this season.