The Domestic Apolitics of 1600 Penn

1600 Penn is not The West Wing with yuks. In fact, considering that it takes place in the White House, the pilot (“Putting Out Fires“) is surprisingly devoid of conventional political engagement. Instead, it acts more as a traditional domestic comedy with the twist that its location contrasts the mundane familiar conflicts. But while this series seems to be an outgrowth of the triumph of style over substance in presidential politics, it holds the potential to highlight the way our current climate politicizes certain personal issues.

1600 Penn is not The West Wing with yuks. In fact, considering that it takes place in the White House, the pilot (“Putting Out Fires“) is surprisingly devoid of conventional political engagement. Instead, it acts more as a traditional domestic comedy with the twist that its location contrasts the mundane familiar conflicts. But while this series seems to be an outgrowth of the triumph of style over substance in presidential politics, it holds the potential to highlight the way our current climate politicizes certain personal issues.

By most accounts (conventional, moderate left) political comedy has flowered on American television in the last decade or two. And while scholarship on this phenomenon largely focuses on the more daring fare offered by late-night and cable programming, this trend is not foreign to primetime. In addition to the old stalwart Simpsons, the various Seth MacFarlane shows – especially American Dad – engage in national political issues on a near-weekly basis. Parks & Recreation offers another example, as Ron Swanson’s lovably misguided libertarianism contrasts with the lessons showing government efficacy – itself a political stance.

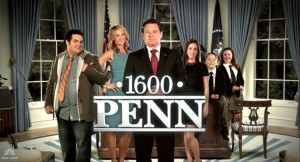

Judging by the pilot, NBC’s new 1600 Penn does not fit into this historical trajectory. Instead, it relies on traditional domestic comedy in the form of interpersonal conflict. Admittedly, the officious situation of this Bill Pullman and Jenna Elfman-starring situation comedy adds a level genre contrast. This amplifies the inherent humor in stock conflicts like those between a button-down father and mischievous child implicitly, and by the press secretary’s attempts to minimize the scandal. However, even in the one plot that is explicitly political – trade negotiations between the U.S. and Brazilian leaders – there are few points to be made about anything explicitly political except for throwaway asides (“Your trade deal will crumble like your nation’s aging infrastructure,” taunts the Brazilian president). Instead, the respective presidents’ machismo exacerbate tensions that are ultimately resolved more by personal appeals and pathos than economic reasoning. And while this resolution is ostensibly political, it serves the narrative more as a way to resolve personal conflict.

To this end, 1600 Penn invites comparisons to That’s My Bush, the short-lived 2001 Comedy Central sitcom parody by South Park‘s Trey Parker and Matt Stone. That’s My Bush operated on a similar conceit of contrasting the high seriousness of the presidency with idiotic sitcom plots, but did so with a sense of gleeful absurdism. Even so, Parker and Stone managed to insert trenchant political points about abortion and capital punishment into their show despite the fact that the primary target of its parodic satire was not politics, but rather the sitcom style itself.

But in its own way 1600 Penn serves as an interesting document regarding the presidential politics of the last fifty years. Historians like Mary Ann Watson and Barbie Zelizer point to Kennedy’s friendly relationship with television as foundational to the current familiarity we have with presidents. Indeed, the recent 2012 presidential election was at least the sixth in a row where discourses surrounding the losing major party candidate focused on his personal squareness and/or stiffness in contrast to the winning candidate’s relative personability and/or coolness. In a world where the personable has become political, we should not be terribly surprised that a television show taking place in the White House can act largely as an nonirionic dom-com.

But in its own way 1600 Penn serves as an interesting document regarding the presidential politics of the last fifty years. Historians like Mary Ann Watson and Barbie Zelizer point to Kennedy’s friendly relationship with television as foundational to the current familiarity we have with presidents. Indeed, the recent 2012 presidential election was at least the sixth in a row where discourses surrounding the losing major party candidate focused on his personal squareness and/or stiffness in contrast to the winning candidate’s relative personability and/or coolness. In a world where the personable has become political, we should not be terribly surprised that a television show taking place in the White House can act largely as an nonirionic dom-com.

On the other hand, elements from the pilot show promise to engage with significant political issues. Two seemingly burgeoning serial plots involve female sexuality in instances where the personal is explicitly political. As the first episode draws to a close, the thirteen-year-old daughter reveals that her crush is named Jessica. Will the first dad (Bill Pullman) be persuaded at the last minute to veto some piece of anti-gay legislation because he comes to understand the issue through the eyes of his daughter’s innocent and inherent love? Or will this become a comedy of hiding her scandalous sexuality? It is difficult to imagine this narrative element not becoming a more pointedly political issue as the series develops.

Similarly, we discover in the pilot that the elder teenage daughter is pregnant, and not by choice. Assuming it lasts long enough, the first season could also offer this plot up as a point for political discussion regarding reproductive rights and unplanned teenage pregnancy or it may become a comedy of bad excuses for morning sickness and loose-fitting blouses. If the latter, it will be obvious that 1600 Penn is explicitly avoiding political engagement of any depth. And if that is the case, why does this show exist?

An afterword:

In last night’s second episode, the daughter’s pregnancy indeed becomes a public issue after it is accidentally leaked to the press. The comedy of vulturous reporters attacking the celebrity family for information implicitly argued for privacy on this matter, suggesting that the show is edging towards more engaged stances. However, celebrity privacy is a different issue from the interpretation of the Constitution as granting privacy from the government in personal matters. At one point, Jenna Elfman’s first lady assures her child that this is a family issue rather than a political one. But that is not true on our side of the screen.