The Power of Women’s Voices in The Great Gatsby

“[T]here was an excitement in her voice that men who had cared for her found difficult to forget: a singing compulsion, a whispered ‘Listen,’ a promise that she had done gay, exciting things just a while since and that there were gay, exciting things hovering in the next hour.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

“[T]here was an excitement in her voice that men who had cared for her found difficult to forget: a singing compulsion, a whispered ‘Listen,’ a promise that she had done gay, exciting things just a while since and that there were gay, exciting things hovering in the next hour.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

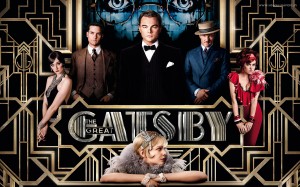

If his classic novel, The Great Gatsby, is any indication, F. Scott Fitzgerald loved the sound of a woman’s voice. The book, upon which Baz Luhrmann’s upcoming film adaptation is based, is like a textual serenade to a thrilling and unique feminine voice that rings out like “a wild tonic in the rain.” Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby will hit theaters this Friday, with Tobey Maguire voicing Fitzgerald’s masculine narrator and Leonardo DiCaprio portraying the mysterious Jay Gatsby. Fitzgerald’s intriguing feminine voice – which belongs to Daisy Buchanan – will be embodied by Carey Mulligan. Gatsby’s promotional materials indicate that Mulligan’s performance will offer the nuanced physical performance demanded by the role – but if Gatsby’s trailers are any indication, Daisy’s voice will have some impressive help from the film’s soundtrack. Her voice carried little influence or power in Fitzgerald’s day – in an age in which “the best thing a girl can be in this world [is] a beautiful little fool” – but Gatsby’s soundtrack artfully blends Fitzgerald’s 1920s female voices with a cast of contemporary female musical powerhouses, who insistently reclaim Daisy’s silenced perspective.

In an effort that delayed the film’s release substantially, Luhrmann recruited Jay-Z to compile an impressive array of top artists. The most impressive among them are women, performers who intimately express the timeless emotional appeal of Fitzgerald’s Daisy. Beyoncé’s collaboration with André 3000, an eerie rendition of Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black,” is an unsettling confession of compulsive loyalty to an unfaithful partner. The vulnerable honesty of Lana Del Rey’s “Young and Beautiful” begs for reassurance that love can outlast youth. And Florence + the Machine’s intensely powerful “Over the Love” nods to Daisy’s gendered social restrictions, channeling the frustration of a woman “borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

On the surface, these songs may not strike a feminist chord. In many ways, they speak to the powerlessness of Fitzgerald’s jazz age women. But while Lana Del Rey, Florence Welch, and Beyoncé, like Daisy, have incredibly memorable voices, their performances are also overflowing with generations of hard-won power. Welch’s voice has been called “hauntingly powerful” and “too loud for the room,” pointing to the brick wall of sound she pushes from her adept Lungs. She describes her music as “something overwhelming and all-encompassing that fills you up,” putting her right at home alongside female mogul Queen Beyoncé’s authoritative style. And while Lana Del Rey’s tender contribution to the musical compilation is more subdued, her industry prowess earned her featured billing. Setting her apart from other contributors, Warner Brothers’ “Soundtrack Sampler” features a still image of Del Rey’s name in the bold, graphic lettering of the film’s title screen.

Regardless of whether these musicians should be considered feminist or not, these songstresses’ massive voices bubble up under the story’s surface, threatening to overturn the masculine narrator’s perspective in favor of Daisy’s lilting voice. Some of the film’s trailers even seem to take on Daisy’s point of view, layering Carey Mulligan’s beautifully nuanced facial reactions to the violence she both witnesses and perpetrates over contemporary female performers’ driving vocals. Daisy’s voice may not have had much power in the jazz age, but with singers like Beyoncé, Welch, and Del Rey to offer their vocal prowess to the character, Daisy’s perspective takes on a whole new meaning for feminism. United with these musicians’ vocal power, Daisy becomes an illustration of where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going.

Fitzgerald describes Daisy’s as “the kind of voice that the ear follows up and down, as if each speech is an arrangement of notes that will never be played again.” I like to imagine the woman whose lilting speech compelled him to craft such a lovely phrase, but like so many women – both historical and contemporary – her voice has been silenced. In performances that truly speak to the power of a musical message, Florence Welch, Beyoncé, and Lana Del Rey have taken up her cause. Together, they remind us of the hope in a powerfully insistent voice. They remind us that some voices are forever silent. And, most importantly, they remind us that our voices – and media soundtracks – can be important feminist tools as we “beat on, boats against the current.”

Thanks, Amanda. This is a discussion of the sonic implications of gender in the soundtrack and hopefully the film that I hope to delve into myself. I’m curious about how the film’s sound(track) is used to distort intersections of contemporary race and gender politics with history and historical narratives. I think it makes history circular instead of linear. This is a dope opener!

~Regina

Thanks for your comment, Regina. I, too, am interested to see how the film shakes out, particularly in terms of race and the soundtrack. I think you make a great point about circular history — cool idea!

Thanks for this, Amanda. I’m curious what you think about the seeming Daisy-centrism of the soundtrack. Certainly there’s something powerful about gathering female vocalists like Beyoncé, Florence Welch, and Lana Del Rey (along with Emeli Sandé, Sia, Fergie, Coco O., and Romy Croft from the xx) for this project. I especially think that Welch’s contribution provides a powerful critique of the subjugation of women at this particular historical moment. And it will be interesting to see how these songs could be activated as feminist commentary within the film and alongside it as a paratext.

But one thing that troubles me about the soundtrack (and really the entire film adaptation, as I’ve been able to glean from the trailers and press discourse) is the thematic privileging of the central romance and the doomed fabulousness of Daisy Buchanan over the book’s scathing critique of class, materialism, and proscribed gender roles. Importantly, Fitzgerald’s critique extends beyond Daisy and creeps into the lives of characters like Myrtle Wilson. It also affects Jordan Baker (aside: my favorite character). So I’m wondering two things. One, when we say “women,” do we mean “Daisy”? Two, can we extend the contributions from this confluence of female pop vocalists to address the subjectivities of the book and film’s central *and* supporting female characters?

Thanks for your comment, Alyx — you make SUCH a great point!

I focused on Daisy here (in part to keep to a reasonable word count), but Myrtle and Jordan have been weighing on my mind as I wait for tomorrow’s midnight showing. Though it is unfortunate, I suspect that most of Fitzgerald’s social commentary will be discarded, which is what draws me to the Daisy-centric (great term!) soundtrack as a small way of reclaiming the text’s potential. I am wondering if maybe the film will use some of its soundtrack women in ways that enhance the supporting characters more — we don’t see much of the other women in trailers, but we also don’t hear nearly all of the soundtrack women in what’s been released so far. Perhaps the soundtrack will give Luhrmann a way of adding depth to these female characters, even if he can’t give them as much screen time.

Sadly, I too anticipate that this adaptation will have shaved away most of the narrative’s complexity in favor of the Daisy/Gatsby story — in fairness, the book as a whole is a really intricate story to tell in two to three hours. Not that it’s any consolation. . .