LeakyCon Portland: Where the Fangirls Are

Last year, I briefly attended the third LeakyCon in Chicago in order to see A Very Potter Senior Year, the one-time-only live performance of the third and final Harry Potter musical parody by the Starkid theatrical troupe. The wait was long, and I found myself in an extended conversation with two con attendees, both 16-year-old girls. They had just come from one of several Young Adult literature panels at the con, which they described in rapturous and articulate detail, and they also insisted that I start watching the web series The Lizzie Bennett Diaries, also represented at the con. Upon sighting a few of the actors who play Warblers on Glee in our Starkid queue, they then launched into a discussion about their concerns regarding Glee’s representation of a transgender character and what they felt was its continued overall “heteronormativity.” Immediately following this conversation, during what proved to be a nearly five-hour-long show, we laughed and wept alongside the actors and the other 3,000 largely female fans.

I was impressed by the tremendous sense of community I felt at LeakyCon, as well as the seamless and untroubled combination of intellectual and emotional engagement with popular culture. I persuaded two fellow scholars, Louisa Stein and Lindsay Giggey, to join me in attending the next LeakyCon in its entirety. The following series of articles represents our analysis of some (by no means all) of the cultural work of LeakyCon Portland 2013. Looking back, my first encounter foreshadowed much of what marked LeakyCon strongly for us this year as well: the convergence of multiple fandoms and platforms, blurred lines between celebrity/performer and participant/audience, aspirational forms of egalitarian community based around shared fandom and continual individual validation (“you/we are awesome!), and a safe space for adolescent identity exploration and self-expression, especially for girls and queer youth.

LeakyCon began in 2009 as a Harry Potter fan convention that sought to combine academic analysis with celebratory fan activity. As organizers explained, what started as two discreet categories soon took on aspects of each other. As the HP franchise ended, organizers expanded the conference to include other texts and fandoms that their attendees were invested in, enlarging the scope of the con while retaining HP as the “mothership” fandom.

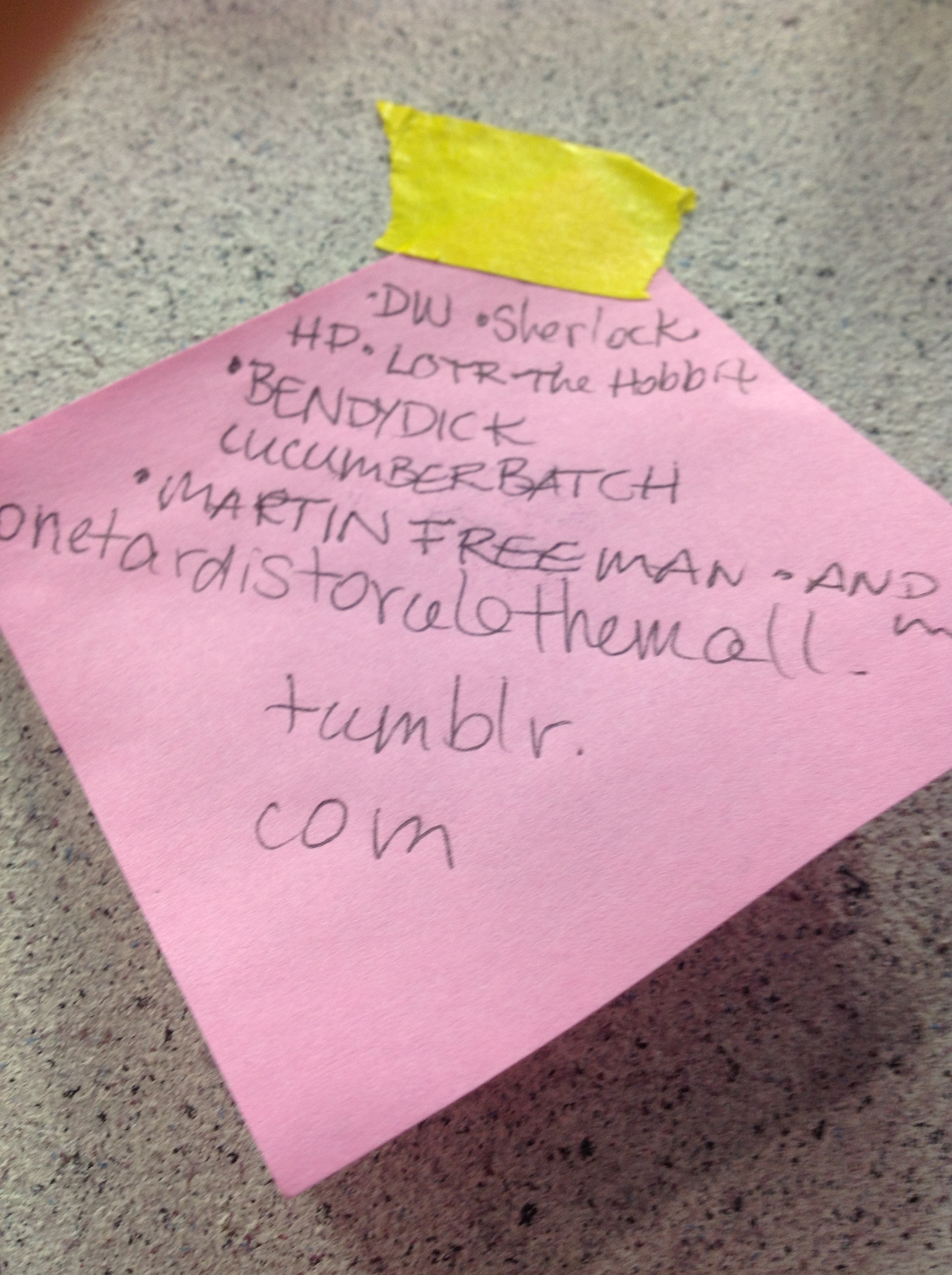

Not surprisingly, social media has been integral to LeakyCon’s success and growth (this summer offers two cons for the first time, one with 5,000 attendees in Portland and the first international con in London, August 8-11, long soldout at 1500; attendees largely buy tickets months in advance — tickets are expensive-$160/350- but all-inclusive). LeakyCon and Tumblr exploded in the fan community at the same time, and Tumblr has become the primary forum of its attendees, who maintain virtual community with each other away from the conference. Attendees indicated their multiple fandoms with tags on their badges, wristbands, and by posting their Tumblr sites and affiliations on a shared wall. Indeed, one could argue that LeakyCon is a much-valued supplement to online community for those who are able to attend, but the shared physical space gives them an opportunity to enjoy the kinds of collective social activities – singing, dancing, chatting in the endless queues – that they cannot do online and that they do not have the opportunity to do in their RL’s (“Real Lives”).

Not surprisingly, social media has been integral to LeakyCon’s success and growth (this summer offers two cons for the first time, one with 5,000 attendees in Portland and the first international con in London, August 8-11, long soldout at 1500; attendees largely buy tickets months in advance — tickets are expensive-$160/350- but all-inclusive). LeakyCon and Tumblr exploded in the fan community at the same time, and Tumblr has become the primary forum of its attendees, who maintain virtual community with each other away from the conference. Attendees indicated their multiple fandoms with tags on their badges, wristbands, and by posting their Tumblr sites and affiliations on a shared wall. Indeed, one could argue that LeakyCon is a much-valued supplement to online community for those who are able to attend, but the shared physical space gives them an opportunity to enjoy the kinds of collective social activities – singing, dancing, chatting in the endless queues – that they cannot do online and that they do not have the opportunity to do in their RL’s (“Real Lives”).

Because LeakyCon started as a conference promoting young adult fiction, its attendees are primarily teens and young adults (although some enthusiastic parents accompanied their children). Being among them, we were constantly struck by the sense, at once, of collectivity and change; this was a generation not concerned about trying to fix themselves within a single frame or role, but a group of people who were celebrating the fluidity and multiplicity of identities, pleasures, and roles that LeakyCon made possible for them to express. Their investment in multiple fandoms reflected their rejection of stable social positioning in other ways as well; they gleefully blurred the lines between gender and sexual norms, teen and twenty-year old “best friends,” high and low cultural tastes and products, and being public and private school kids, in the same way that they embraced being performers and audience members, intellectuals and fans, and Whovians and Starkids. “My two friends and I, “ one 15-year-old reported to me, “we cover the spectrum.” I wasn’t sure what constituted “the spectrum,” but I was struck by how matter-of-fact she was about it. LeakyCon is, in so many ways, a fluid, queer space, and that’s what the fans value about it. Fandom unites them, but it has also clearly permitted them to bridge other social divides that would have otherwise been much more difficult for them, especially as the nerdy, bookish adolescents many LeakyCon fans also claim proudly to be.

The LeakyCon opening ceremonies was a perfect illustration of the multiplicity, social blurring, and queer space the con offers its attendees. Stars became fans by dressing as favorite characters: this year’s con brought together characters (and several actors) from Disney, Star Wars, Glee, The Hunger Games, Lord the Rings, Buffy, Dr. Who, and Sherlock as well as Harry Potter. These multiple fandoms represented the overlapping opportunities for fan identification, desire, and pleasure offered at LeakyCon, and the performance concluded with a remarkable affirmation of fandom’s queer space led by Rent star and author Anthony Rapp, who parodied his B’way role in a Leaky version of “La Vie Boheme.” This number depicts LeakyCon as home to a multifandom culture that celebrates all things geeky, fannish, and creative.

To writing fiction…fanfiction

A world without restriction

A prediction my friends.

We’ll be geeky through and through. – LeakyCon, 2013.

For more on LeakyCon 2013, read:

– Part two (“On Wearing Two Badges“)

– Part three (“Fans and Stars and Starkids“)

– Part four (“From LGBT to GSM: Gender and Sexual Identity among LeakyCon’s Queer Youth“)

– Part five (“Inspiring Fans at LeakyCon Portland“)

– Part six (“Redefining the Performance of Masculinity“)

– Part seven (“Embracing Fan Creativity in Transmedia Storytelling“)

Rereading this now, with some more distance from the con, I found myself struck by the way congoers negotiate the differences between community online and off–trying to assert online culture in an offline space. The most clear example is certainly the wall-of-tumblr, but I’m also thinking of the refrain of meetups where people shouted out pairings or fanfic as a way of communicating these various elements of not only what they like/their fluid identities (thinking ahead to your later post) but of where they participate online and what their online experience is. At the time I was a little thrown by the lack of substantial engagement in those meetups, but I think I’m coming to realize that wasn’t the point; maybe the point was more to signal ongoing substantial engagement that’s already happening online? Like it didn’t actually need to be recreated at LeakyCon, just acknowledged and built upon?