Self-Important Spectacle: The 2013 Emmy Awards

When Stephen Colbert accepted his first of two awards on behalf of his team at The Colbert Report, which took home the Emmy for Writing for a Variety Series before ending compatriot Jon Stewart’s 10-year run in the Outstanding Variety Series category, he said he believed the Emmys were great this year. It was a joke because he was implying the Emmys were only great because he won; it was a successful joke because the Emmy ceremony had been, to that point, an unmitigated trainwreck of a production.

When Stephen Colbert accepted his first of two awards on behalf of his team at The Colbert Report, which took home the Emmy for Writing for a Variety Series before ending compatriot Jon Stewart’s 10-year run in the Outstanding Variety Series category, he said he believed the Emmys were great this year. It was a joke because he was implying the Emmys were only great because he won; it was a successful joke because the Emmy ceremony had been, to that point, an unmitigated trainwreck of a production.

The Emmys began late due to a mess of a football game, where the New York Jets managed to sneak out a victory after setting team records for penalties and penalty yards. It was an omen for the night to come, where any objective referee would have penalized Ken Ehrlich and his production team on countless occasions. From the moment the ceremony began with an aimless sequence where the Emmy production team proved their ability to edit footage from various television shows together into fake conversations between television characters, it was clear that this was an evening set to celebrate television in the most misguided of ways.

It was unfortunate for the show’s producers there was no clear narrative that emerged out of the night’s winners: the Netflix ascension never materialized, Breaking Bad expanded its trophy case with wins for the show and Anna Gunn but didn’t dominate as it could have, and Modern Family went unrepresented in acting categories for the first time but nonetheless won the one that matters, Outstanding Comedy Series. It means the telecast itself becomes the narrative, and a rather unpleasant one at that.

There were the special eulogies for individuals who had passed on, which drew controversy for selective criteria in advance of the ceremony and criticism from viewers and winners—Modern Family’s Steven Levitan—for giving the evening a somber tone. There was the choice to maintain the audio feed in the theater for the In Memoriam segment itself, enabling the always tacky “Applause Meter” to judge the level of celebrity on display. There was the nonsensical appearance of Elton John to perform a new song that “reminds him” of Liberace only to attempt to justify his appearance given his nonexistent relationship to television. There was the excruciating opening segment that transitioned from the aforementioned pre-taped sequence to a lazy Saturday Night Live monologue where a parade of previous Emmy hosts were wasted right up until the point Tina Fey and Amy Poehler momentarily wrestled the show from its imminent doom.

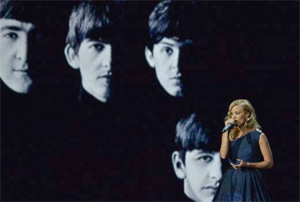

And yet it was the look back in television history to the year 1963 that best encapsulates the broadcast’s problems. Combining a superfluous performance of The Beatles’ “Yesterday” from Carrie Underwood with a Don Cheadle-delivered retelling of a tumultuous year in our history, it sought to position television at the forefront of culture. It was television that helped the nation heal about JFK’s death, gave Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” resonance, made The Beatles the phenomenon they would become, and—in an awful segue—continues to serve as the launching pad for musical acts like Underwood. Anyone with an understanding of history—yet alone media scholars—would have scrawled all over their script, which fails to cite sources to support any of these overly simplistic claims.

In addition to this problem, however, it was also a sequence that implicitly argued the Emmys exist not simply to acknowledge the best in television, but also to reaffirm to us that television is an important part of society, and that—according to Television Academy chairman Bruce Rosenblum during his annual spiel—the Academy is there 365 days a year to help make this “golden age of television” a reality. This rhetoric was also evident in the sequence where Diahann Carroll read a prepared statement about her impact as the first African American actress nominated for an Emmy, turning over the microphone to Scandal’s Kerry Washington; it was the Emmys touting their progressivism, a noble gesture that does not change the dramatic underrepresentation of men and women of color both at the Emmys and on TV in general, and does not magically transform the Television Academy into the Peabody Awards overnight.

The Emmys are at their worst when they feel as though they are about the Emmys. As someone who has over time accumulated a wealth of knowledge about the Emmy Awards as an institution, I reveled in Ellen Burstyn joking about the screen time for her previous nomination and often found Ken Ehrlich’s broadcast fascinating in its tone deafness, but its ultimate failure is both undeniable and unfortunate when I consider the worthy—if, yes, also wealthy—winners whose personal and professional triumphs were overshadowed by the spectacle or lack thereof around them.

The most frustrating detail was in the special choreography segment featured in the broadcast’s final hour. For most viewers, the routine inspired by nominated series was representative of the hokey, misguided production numbers elsewhere in the broadcast. However, for me it was a rare case of one of the Creative Arts categories—consigned to a previous ceremony, which this year aired as a tape-delayed, edited two hours on FXX—being elevated to the main stage, with the choreographers—many of whom I respect based on their work on reality stalwart So You Think You Can Dance—nominated for their work in television being given an expansive platform for their work and an acknowledgment of their labor.

Whereas FXX’s broadcast only acknowledged nominees for guest acting awards, and aired only small portions of winners’ already short speeches, for a brief moment the Academy recognized the work of choreographers at the Emmys itself; it was unfortunate that what surrounded it so diminished the meaning of the performance. It was a broadcast that prioritized promotable musical acts at the expense of time for television professionals to accept their awards, so busy performing the “importance of television” that it forgot what—or who—actually makes television, if that was something the Academy even knew in the first place.

Myles,

In the interest of conversation, do you care to take a crack at explaining why I should invest in the Emmy Awards at all? I am absolutely interested in your consideration of the Academy industrially, and I do appreciate critique of the ceremony as a TV program (trying to earn eyeballs and advertising dollars). But there has long been a central dilemma in that awards based on the viewing of one episode undermine the superlative, “outstanding SERIES.” I found myself pretty horrified by what some call “shockers” and others might call “significant flaws with process.” What do argue is the larger role of the Emmy Awards within the study of television, and how high are the stakes for all looking for a vehicle to encourage innovative and/or excellent work?

Thanks for your thoughtful comments (and for writing them so quickly–I was up when it went live, and I was deeply impressed.)

This is, as you acknowledge, a larger question.

To take a brief crack at it, however, the Emmys have historically functioned as a space of legitimation, a function that we can obviously deconstruct and which is undoubtedly undermined by the process’ incapacity to judge television as an ongoing medium (with showy individual episodes beating out season-long performances). Looking to the Emmys as the arbiter of quality and taste is just as empty as looking at anyone or anything as the arbiter of quality and taste—such an arbiter does not and should not exist.

That being said, what interests me about the Emmys—and which to me gives them value—is the ways in which the industry seeks equal measures of validation of and distance from Emmy glory. The broadcast networks rely on the Emmys broadcast as a way to draw viewers and gain promotional attention for their own series when it’s their turn, while lamenting they have to provide free promotion for cable channels; the cable channels dismiss the importance of broadcast television but rely on the exposure from the Emmys to build subscriptions or encourage viewership. The Emmys have been at the center of the rise of cable, the rise of premium cable, the so-called “death of the broadcast networks,” and now the rise of Netflix, and over time have made numerous adjustments to the voting process and the voting rules in response to changes happening around them. In the end, however, they remain largely the same, just as television as a form has essentially endured despite such a tumultuous recent history.

What makes the Emmys interesting to me is that they’re not a reflection, but rather an active participant in these discourses of both television legitimation and the so-called “future of television,” a prism through which we can gain insight into how the industry understands—or doesn’t understand—these changes. The same goes for every awards show, whether the Grammys or the Oscars, but the television landscape changes so much more often that the Emmys offers a particularly rich case study for these industrial ebbs and flows. Rather than ascribe them importance over what television is good or bad, for me studying the Emmys acknowledges their participation in industrial discourses that seek to lay claim over those values.

I don’t know if this means we should invest in who does or does not win Emmy Awards—I often find myself doing this, but only because I watch a lot of TV and like to see performers I admire being rewarded. However, I do think we should invest in contextualizing the Emmys in an industrial context, even if we accept the facile nature of the exercise as it is positioned by the Academy in instances like this broadcast.