The Cosmopolitan City and the Carnivalesque in Arcade Fire’s Reflektor Campaign

On August 1, a mysterious Instagram account initiated the ambitious multi-media, multi-platform promotional campaign for Arcade Fire’s new single and album of the same name, Reflektor. Additionally, the campaign incorporated a Saturday Night Live performance, YouTube clips, an NBC late-night special, Here Comes the Night Time, reminiscent of community public access television (an aesthetic taken up and inserted back into popular culture by the likes of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!), and a low-quality album stream leaked intentionally by the band. Undoubtedly, the campaign reflects an increasingly mobile and interconnected listening and viewing experience of popular culture, for which its key components of excess and ubiquity were integral to its effectiveness (for more on this, see R. Colin Tait’s thorough account of the ubiquity and virality of The Beastie Boys’ “Fight for Your Right Revisited“). Early in the Reflektor campaign, a series of Instagram photos hinted at the significance of “9 PM 9/9.” The date and time in question ended up being the first of a series of “secret” shows by the band, billed not as Arcade Fire but instead as The Reflektors. These hyped events with costumed guests would significantly anchor much of the campaign as it unfolded and intensified, highlighting the persistent significance and centrality of local sites of production in popular music-making and promotion.

On August 1, a mysterious Instagram account initiated the ambitious multi-media, multi-platform promotional campaign for Arcade Fire’s new single and album of the same name, Reflektor. Additionally, the campaign incorporated a Saturday Night Live performance, YouTube clips, an NBC late-night special, Here Comes the Night Time, reminiscent of community public access television (an aesthetic taken up and inserted back into popular culture by the likes of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!), and a low-quality album stream leaked intentionally by the band. Undoubtedly, the campaign reflects an increasingly mobile and interconnected listening and viewing experience of popular culture, for which its key components of excess and ubiquity were integral to its effectiveness (for more on this, see R. Colin Tait’s thorough account of the ubiquity and virality of The Beastie Boys’ “Fight for Your Right Revisited“). Early in the Reflektor campaign, a series of Instagram photos hinted at the significance of “9 PM 9/9.” The date and time in question ended up being the first of a series of “secret” shows by the band, billed not as Arcade Fire but instead as The Reflektors. These hyped events with costumed guests would significantly anchor much of the campaign as it unfolded and intensified, highlighting the persistent significance and centrality of local sites of production in popular music-making and promotion.

The parameters of the campaign suggest that it is no longer enough to simply promote one’s music through the channels offered and preferred by big industry players (i.e. Arcade Fire’s aforementioned NBC special that starred celebrities like Bono and James Franco and the SNL performance), nor to only draw upon avenues in line (philosophically and practically) with more independent means for circulating and promoting music. We are in the midst of a messy, conflicted, yet exciting moment when new promotional practices are being tested against big industry methods for producing, circulating, and performing music. And thus we get the conflation of an unknown band, The Reflektors, and the Grammy award-winning Arcade Fire.

Arcade Fire’s Reflektor campaign overwhelms all channels of communication and ensures a presence on multiple platforms through which today’s music fan interacts with music on a daily basis, both in-person or locally and online. But the campaign also emphasizes local sites of production and exhibition in popular music-making. And more importantly, the campaign has been centered on cosmopolitan cities with rich and diverse cultural and musical histories, namely Montreal and New York. The cosmopolitan city is reflected in both the campaign and the band’s current musical sound and style, and it is the new location in a series of Arcade Fire albums that foreground place – a Montreal borough on Funeral, a church-turned-studio on Neon Bible, and, of course, the alienating Houston suburbs on Suburbs.

While other cities have been integrated into the campaign, Montreal and New York have been particularly central, each doubling as a significant site of production for the band.

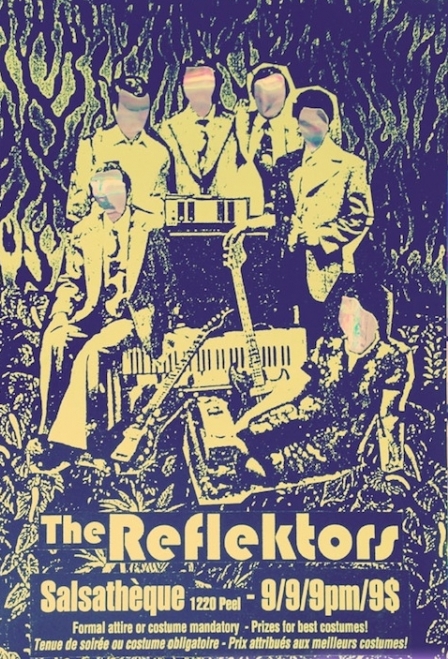

A poster for Arcade Fire’s “not-so-secret” secret show as The Reflektors at Salsatheque in Montreal.

Montreal, the band’s home, served as the site for the first show by The Reflektors. A review of the “not-so-secret show” at Salsathèque (a salsa club, not so much a rock venue) was described as “the (local) climax of an elaborate viral marketing campaign for their new single ‘Reflektor.’” The show would become the basis of the late-night NBC special, Here Comes the Night Time (the cosmopolitan city doesn’t sleep), as well as for a number of teaser trailers for the album. Reviewer Lorraine Carpenter points to the Haitian influences that have been added to the band’s look and sound. The band and the city of Montreal are both connected to Haiti. Montreal’s Haitian community is the largest in Canada and band member Régine Chassagne, whose parents emigrated from Haiti, has advocated the country’s need for aid following the 2010 earthquake. The sounds of the diasporas are the sounds of the cosmopolitan city.

Next, The Reflektors headed to Brooklyn, New York, to play two back-to-back events that would, amongst other things, carry the campaign into satellite radio through heavy promotion by Sirius XMU. New York is one of the cities where the album was recorded, with production by New York-based James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem (whose synths and drum beats are very much palpable on not just the single “Reflektor” but throughout the whole album). Artists who have been cited in reviews as standout influences on Reflektor (Talking Heads, for one, a comparison made ad nauseum) evoke a New York as heard through the coming together of sounds and styles both distant and local at key moments in the city’s musical history, namely proto-punk in the mid-1960s to mid-1970s (Bowie’s backing vocals on “Reflektor” are key here) and disco (Studio 54) of the late 1970s.

Following the Montreal and Brooklyn shows, The Reflektors continued the series of secret shows in other cities including Los Angeles and Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood, with funds donated to Partners in Health and the neighborhood’s cultural center. Only these subsequent shows were not as integral to the campaign itself.

It is important to consider what it means to evoke the cosmopolitan city through sound. Cultural capital is required for navigating and traversing the global and weaving it through the local and this is a privilege attainable through a successful career. Arcade Fire’s cultural accolades and accomplishments (The Suburbs won the Polaris, the Juno, and the Grammy for best album of 2011) are instrumental in this transition from the suburbs to the cultural and musical diversity evoked by the cosmopolitan city. Trips to Haiti, specifically the Carnival in Jacmel, become components of the campaign.

Also connecting the campaign to the cosmopolitan city is a notion of excess, evidenced by the recurring theme of the carnival and Bakhtin’s notion of the carnivalesque. The campaign saturates a wide range of media outlets just as the city’s carnival overwhelms the senses. A multi-platform, intermedia campaign is a modern carnival steeped in excess; chaos and humor unfolding in reviews, reader comments, internet trolls, tweets, and blog posts. In person at the secret shows, concert-goers were required to be costumed and masked.

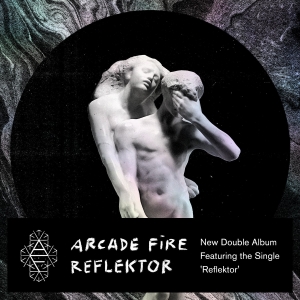

To further drive the point home is the myth of Orpheus that recurs throughout the campaign. Auguste Rodin’s sculpture of Orpheus and Eurydice is the album’s cover, there is a song titled “It’s Never Over (Oh Orpheus),” and the album leak was paired with Black Orpheus, Marcel Camus’ 1959 film that takes place during Brazil’s Carnaval. Many reviews of the album have pointed to the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice as it pertains to the theme of reflection, but what is also of significance is that Orpheus is killed by the mythic agents of the carnivalesque, torn apart by Dionysus’ maenads. And here we can locate an important message that the band communicates through the campaign: to be wary of the ways in which the self is cut and chopped into fragments online and in contemporary culture. Our reflections, of our reflections, of our reflections.

[…] my latest contribution to Antenna on the importance of place – and cosmopolitanism and the carnivalesque – in Arcade […]