#SCMS14: Klout & The ‘Influence’ Economy

Last week I attended my first SCMS Conference and had a wonderful time meeting fellow scholars and witnessing the future of our discipline. While I had several conversations with people in panels, lobbies, and various establishments across Seattle, I quickly realized there was a second conversation occurring on the Twitter backchannel centered around #SCMS14. A standard feature of many academic conferences, the official conference hashtag provides a secondary site for scholarly engagement and discussion as well as another method for networking, only this time through digital media. My recent research interests have begun to focus on the ways people present and promote themselves on social media like Twitter, and #SCMS14 provides a unique vantage for the increasing role our social media identities play in our professional lives. The idea of not just having a social media presence but an influential one as being crucial to one’s career is still a young concept, but one worth further exploration.

Last week I attended my first SCMS Conference and had a wonderful time meeting fellow scholars and witnessing the future of our discipline. While I had several conversations with people in panels, lobbies, and various establishments across Seattle, I quickly realized there was a second conversation occurring on the Twitter backchannel centered around #SCMS14. A standard feature of many academic conferences, the official conference hashtag provides a secondary site for scholarly engagement and discussion as well as another method for networking, only this time through digital media. My recent research interests have begun to focus on the ways people present and promote themselves on social media like Twitter, and #SCMS14 provides a unique vantage for the increasing role our social media identities play in our professional lives. The idea of not just having a social media presence but an influential one as being crucial to one’s career is still a young concept, but one worth further exploration.

For proof of the perceived importance of such a concept as digital social influence, one need look no further than Klout. The website/app uses analytics drawn from a user’s various social media profiles (like Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.) to award the user a “Klout Score,” a numerical value between 1-100 that supposedly ranks one’s online social ‘influence.’ The Klout Score is based on multiple variables that can be summarized into three categories: True Reach, Amplification Probability, and Network. True Reach relates to the number of people your posts are reaching and how ‘engaged’ that audience is with your posts. Amplification is based on the type of engagement: how likely a post will be “Liked,” reposted, or replied to. Finally, the Network score looks at how influential your engaged audience is and boosts or lowers your score depending. In other words, you have to have influential friends if you want to be influential yourself!

Such metrics sound important to any business or company operating a social media account, and make no doubt that Klout offers business-appropriate analytic tools as well. But the concept of quantifying something as ephemeral and personal as ‘influence’ seems like more of digital media’s ‘softwarization’ of our everyday lives. Klout can be seen as yet another example of what David Berry refers to as lifestreaming, the growing use of self-monitoring technologies leading to a more “quantified self.” By quantifying something as fleeting (yet important) as online influence, several real-world behaviors are at stake.

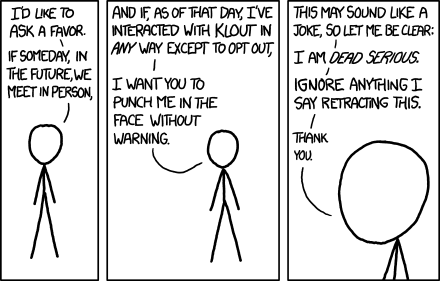

If you’ve read this far and are wondering, “Who the hell would want or care about a Klout Score,” you aren’t the only one. Articles and online comics have already begun questioning the idea of a quantifiable metric for social influence and what purpose it serves other than to somehow feed a narcissistic ego. But the allure of big data might sway some companies, as being able to prove social influence could be seen as a big help in getting a job in any blogging, marketing, or online publishing field. And none of this yet looks at Klout’s own business model, which sees businesses like McDonald’s, Sony, Red Bull, Revlon, Chevy, and more offering Perks to users with high enough Klout scores in relevant social categories. The attainment of Perks doesn’t require the earner to promote the product, but the hope is that such corporate goodwill influences the user to spread the good word of the folks at (Insert Company Here).

If you’ve read this far and are wondering, “Who the hell would want or care about a Klout Score,” you aren’t the only one. Articles and online comics have already begun questioning the idea of a quantifiable metric for social influence and what purpose it serves other than to somehow feed a narcissistic ego. But the allure of big data might sway some companies, as being able to prove social influence could be seen as a big help in getting a job in any blogging, marketing, or online publishing field. And none of this yet looks at Klout’s own business model, which sees businesses like McDonald’s, Sony, Red Bull, Revlon, Chevy, and more offering Perks to users with high enough Klout scores in relevant social categories. The attainment of Perks doesn’t require the earner to promote the product, but the hope is that such corporate goodwill influences the user to spread the good word of the folks at (Insert Company Here).

In other words, now everyone can become a celebrity! Just as stars are given free clothes, cars, and more simply because they are frequently seen, now everyone can get that treatment if they have enough (‘important’) people following them and engaging with them on a frequent basis. By attempting to establish an ‘influence’ economy, Klout begins to blur the line between celebrity and the everyday, where celebrity isn’t a separated social class but a process one can work towards. Being ‘Internet Famous’ is no longer seen as a lower status to ‘real-life’ fame. The two are blurring together, making it less likely to be one without the other.

This all brings us back to all us academics following and contributing to #SCMS14. I returned home from Seattle expecting my engagement during the conference would drastically boost my Klout Score from my middling 50 (I swear it’s for research!), but alas, I was denied. Now I’m not blaming all of you folks for not being influential enough to make my engagements with you count for more. What I am proposing is that we spend more time reflecting on the purpose behind and impact of our online social engagements. We might not be interested in becoming ‘Internet Famous’ or growing our Klout Score to earn some great Perks from Samsung, but we ought to be concerned about how our actions are being perceived and the type of personas we are crafting. Relatedly, we also need to be mindful and cautious of quantifying ourselves when the prospect is becoming so easy. If there is anywhere we should be thinking qualitatively, it is in our social interactions. My fear is the more we spend time putting ourselves onto digital platforms, the more we seem interested in putting digital platforms onto ourselves.

Note: Talk about timing! The day this post was saved to go live, Klout was purchased by Lithium for $200 million. Make of this what you will, but this only adds support to the idea of quantifiable online influence.