She’s Just Being Riley: The Sexual Politics of Girl Meets World

Discussing Girl Meets World without reference to its predecessor, 90s TGIF staple Boy Meets World, is an impossible proposition. Yet despite the presence of BMW stars Ben Savage and Danielle Fishel, GMW works hard to establish itself as a separate entity. This separation lacks subtlety but excels in efficiency; in the first minute of the pilot, BMW protagonist Cory explicitly instructs his daughter, Riley, to turn “his” world into “her” world, and off she goes.

Discussing Girl Meets World without reference to its predecessor, 90s TGIF staple Boy Meets World, is an impossible proposition. Yet despite the presence of BMW stars Ben Savage and Danielle Fishel, GMW works hard to establish itself as a separate entity. This separation lacks subtlety but excels in efficiency; in the first minute of the pilot, BMW protagonist Cory explicitly instructs his daughter, Riley, to turn “his” world into “her” world, and off she goes.

The choice to target the same child and tween demographic that BMW once attracted, rather than the nostalgic millennial audience, is a smart and unsurprising choice for the Disney Channel. The swapping out of “boy” for “girl,” however, is a far greater change than the generational shift, and it is gender that truly separates the spin-off from its parent program. Unfortunately, from a feminist perspective, the execution of these gendered differences leaves much to be desired.

In BMW, protagonist Cory was the straitlaced, middle-class kid from a nuclear family; his best friend, Shawn, was the cocky daredevil from the trailer park. That dichotomy is replicated here in Riley and BFF Maya, but it’s not just Maya’s AC/DC t-shirt and refusal to do homework that mark her rebellion–it’s her sexuality. While Riley is barely starting to experiment with lip gloss, “cool” adult women in the subway remind Maya about the importance of walking provocatively. While Maya is willing to seduce a strange boy on the train as a game, Riley is left terrified and babbling when she trips and falls into the same boy’s lap.

In BMW, protagonist Cory was the straitlaced, middle-class kid from a nuclear family; his best friend, Shawn, was the cocky daredevil from the trailer park. That dichotomy is replicated here in Riley and BFF Maya, but it’s not just Maya’s AC/DC t-shirt and refusal to do homework that mark her rebellion–it’s her sexuality. While Riley is barely starting to experiment with lip gloss, “cool” adult women in the subway remind Maya about the importance of walking provocatively. While Maya is willing to seduce a strange boy on the train as a game, Riley is left terrified and babbling when she trips and falls into the same boy’s lap.

The contrasts come up again and again in this middle school virgin/whore morality play, a theme made explicit when class nerd Farkle walks into the cafeteria with a slice each of angel food and devil’s food cake. And while Maya is never specifically reprimanded for the sexualized aspects of her behavior, the moral of the pilot is that Riley should “be herself” and keep her best friend out of trouble, not try to become her. The girl from the wrong side of the tracks is allowed to be the “whore” in need of saving, but Cory and Topanga’s baby girl must remain pure.

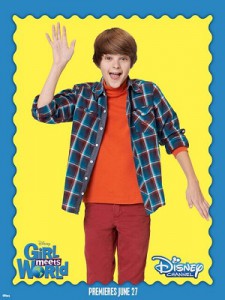

Aside from the virgin/whore themes, Farkle is the show’s biggest problem. His BMW counterpart was Minkus, the obnoxiously nerdy thorn in Cory and Shawn’s sides. But because Minkus was a boy on a heteronormative TV show, his annoying behavior toward the protagonists never veered into sexual territory. If Farkle’s archetype had been gender-flipped the same way Riley’s and Maya’s were, perhaps the character could have worked. Instead, viewers are treated to a character whose defining characteristic is his repeated and unproblematized sexual harassment of the main characters.

Aside from the virgin/whore themes, Farkle is the show’s biggest problem. His BMW counterpart was Minkus, the obnoxiously nerdy thorn in Cory and Shawn’s sides. But because Minkus was a boy on a heteronormative TV show, his annoying behavior toward the protagonists never veered into sexual territory. If Farkle’s archetype had been gender-flipped the same way Riley’s and Maya’s were, perhaps the character could have worked. Instead, viewers are treated to a character whose defining characteristic is his repeated and unproblematized sexual harassment of the main characters.

Then there’s the third problem: Cory himself, whose reaction to Riley’s interaction with boys is not so much paternal as paternalistic. When Riley is interested in a boy, Cory physically carries that boy out of the room. Yet when Farkle literally takes over Cory’s history class to rhapsodize on his “love” for both Riley and Maya, an affection the girls visibly do not share, Cory lets it proceed without complaint. As the parental and academic voice of reason and the primary nostalgic connection to the previous show (Topanga, sadly, has almost nothing to do in this pilot), Cory’s behavior is unconscionable; in just 22 minutes, he manages to deny his daughter sexual agency in two completely different ways.

BMW always had romantic elements; the characters who would become Riley’s parents first kissed in the fourth episode of season one. Yet the romance was never as all-encompassing in the pre-high school seasons as it is in GMW’s pilot, and it wasn’t confused with sexual harassment or the paternalistic determination of acceptable female sexual expression. In fact, one of BMW’s most triumphant episodes is season four’s “Chick Like Me,” in which Shawn and Cory pose as women and learn hard lessons about the kind of harassment women and girls deal with daily.

BMW always had romantic elements; the characters who would become Riley’s parents first kissed in the fourth episode of season one. Yet the romance was never as all-encompassing in the pre-high school seasons as it is in GMW’s pilot, and it wasn’t confused with sexual harassment or the paternalistic determination of acceptable female sexual expression. In fact, one of BMW’s most triumphant episodes is season four’s “Chick Like Me,” in which Shawn and Cory pose as women and learn hard lessons about the kind of harassment women and girls deal with daily.

The change, however, is not surprising. BMW premiered at a time when “girl shows” were few and far between; most American children’s programming circa 1993 featured a male protagonist or a mixed-gender ensemble. The few girl-centric live-action shows that did exist, like Clarissa Explains it All, were in many ways feminist reactions against these boy-centric narratives. But in the two decades since, Disney and Nickelodeon have produced a slew of sitcoms with tween girl protagonists, creating the mold into which GMW is expected to fit itself.

This balancing of genders in children’s programming is a welcome step forward, but there are crevices of that mold that would be better left unfilled – like the prominent use of sexual harassment as humor in shows like Hannah Montana and iCarly. Though these problematic themes are by no means new (Steve Urkel from Family Matters and Roger from Sister, Sister existed contemporaneously with BMW), they have become codified elements of the tween girl sitcom as it exists today, and GMW is following that code.

Many of the elements that made BMW so charming are still present in GMW: tweens figuring out their place in the world, devoted best friends with opposite personalities, and the thematic tying together of school lessons and life lessons. I applaud the creators for bringing those tropes into an explicitly female space. But Girl Meets World is also burdened by the normalized sexism found in girls’ programming of the past two decades, and that may prove to be its creative and political downfall.