“Hollywood Goes to Harlem”: Radio’s Creation of an African-American Film Star

Eddie Anderson quickly became so identified with “Rochester” that he adopted it as his stage name.

Post by Kathy Fuller-Seeley

University of Texas at Austin

Seventy-five years ago, history was made in Harlem when the first elaborate Hollywood film premiere was held in the cultural capital of Black America. Paramount touted “Hollywood goes to Harlem!” as the studio sponsored twin world premieres of the film Buck Benny Rides Again—one at its flagship Paramount Theater in Manhattan (breaking all previous box office records), and the other held on the night before, on April 23, 1940, at the Loew’s Victoria Theater, a 2,400 seat picture palace located on 125th Street in Harlem, adjacent to the Apollo. Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, Jack Benny’s co-star in everything but actual billing, was given the “hail the conquering hero” treatment—an estimated 150,000 people lined the streets as Anderson and dignitaries paraded to the theater. Jack Benny, radio cast members, film director Mark Sandrich and Benny’s comic nemesis Fred Allen all appeared on stage to praise him. Anderson was honored with receptions at the Savoy Ballroom and the Theresa Hotel, and lauded by the nation’s black press.

Anderson’s role in the film as Jack’s valet “Rochester” carried over from radio, featuring witty retorts to the Boss’s egotistical vanities, croaked out in his distinctive, raspy voice. The role positioned him as one of the most prominent African-American performers of the era, despite—and because of—racial attitudes of the day.

Buck Benny was among the highest grossing movies of the year at the American box office in 1940. Throughout the nation, movie theaters billed the film on marquees as co-starring Benny and “Rochester.” In many theaters, especially African-American theaters in the South and across the nation, the billing put “Rochester’s” name first above the title. Anderson and Benny were named to the Schomburg Center Honor Roll for Race Relations for their public efforts to foster interracial understanding. This moment before World War II further raised the consciousness of a young generation of African-Americans to fight for civil rights, while racist white backlash coalesced to further limit black entertainers in American popular media. Anderson’s success caused him to be hailed as being a harbinger of a “new day” in interracial amity and new possibilities for black artistic, social, and economic achievement.

Recent commemorations of the 75th anniversaries of the release of several of classical Hollywood’s most iconic films include an exhibit at the University of Texas’s Ransom Center Archives on “The Making of Gone with the Wind.” Inescapable in discussion of GWTW’s impact is analysis of the shameful prohibitions in Atlanta, the South, and much of the nation against honoring the performance of actress Hattie McDaniel, who won an Oscar as Best Supporting Actress for her role as Mammy. Depictions of black characters in the novel and film were the subject of continuing sharp criticism in the black community. Complicating the story of racism, racial attitudes and restrictive limits on representations of African-Americans in film and popular entertainment media in this era, however, is Anderson’s radio-fueled stardom. A middle-aged dancer, singer, and comic who’d forged a regional career in West Coast vaudeville and mostly un-credited servant roles in Hollywood films, Anderson rocketed to stardom due to his role on Jack Benny’s Jell-O program, one of the top-rated comedy-variety programs on radio. It took the “inter-media” mixture of the two rival entertainment forms of film and broadcasting, along with the input of different decision makers (NBC, sponsor Jell-O, show creator and star Benny, Paramount director Mark Sandrich) to create this interstitial space to foster Anderson’s fame.

Anderson’s “Rochester” role in his first years on Jack Benny’s radio program (1937-1938) had contained heavy doses of minstrel stereotypes—stealing, dice-playing, superstitions—but from the beginning the denigratory characteristics were counterbalanced by the character’s quick wit and irreverence for Benny’s authority, accentuated by his inimitable voice and the wonderful timing of his pert retorts and disgruntled, disbelieving “Come now!” Rochester critiqued Benny’s every order and decision, with an informality of interracial interaction unusual in radio or film depictions of the day. The radio show writers gave Rochester all the punchlines in his interactions with Benny. His lively bumptiousness raised his character above other, more stereotypical black characters. Rochester could appeal to a wide variety of listeners, as Mel Ely suggests of Amos n Andy. He always remained a loyal servant and had to follow Benny’s orders, so he was palatable to those listeners most resistant to social change. Yet, in a small way, Rochester spoke truth to power, and he was portrayed by an actual African-American actor, so he gained sympathy and affection among many black listeners.

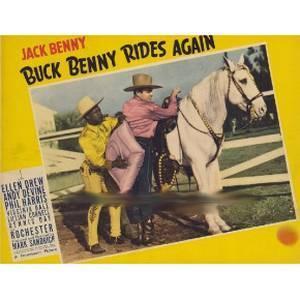

Lobby card for “Buck Benny Rides Again” (1940).

Paramount had sought to translate Jack Benny’s radio popularity into film success for several years, but it was the creative ideas of Mark Sandrich that finally brought success. During the production of his first Benny movie, Man About Town (1939) Sandrich increasingly expanded Anderson’s small role to showcase the strong comic chemistry between Jack and Rochester. Its June 1939 premiere in Benny’s hometown, Waukegan, IL, drew 100,000 spectators to parades and radio broadcasts, and reviewers unanimously praised Anderson for “stealing the film” from Benny. While high-brow critics ranted that both these films were uncinematic, no more than filmed radio broadcasts, the public delighted in seeing the popular characters interact on screen.

The success of Eddie Anderson’s co-starred films with Jack Benny fueled optimistic hopes in the black press that prejudiced racial attitudes could be softening in the white South. Rochester was hopefully opening a wedge to destroy the old myths that racist Southern whites refused to watch black performers, the myths to which film and radio producers so stubbornly clung. The Pittsburgh Courier lauded Anderson as a “goodwill ambassador” bringing a message of respectability and equality to whites in Hollywood and across the nation.

Eddie Anderson was perfectly positioned in 1940, through a stardom that merged radio and film, to represent that optimistic hope that perhaps race relations and opportunities for blacks were improving. The hurtful representations of blacks in the mass media of the past could finally be put aside, The California Eagle optimistically argued in an editorial:

…two years ago American became conscious of a new thought in Negro comedy. It was really a revolution, [emphasis mine] for Jack Benny’s impudent butler-valet-chauffer, “Rochester Van Jones” said all the things which a fifty year tradition of the stage proclaimed that American audiences will not accept from a black man. Time and again, “Rochester” outwitted his employer, and the nation’s radio audiences rocked with mirth. Finally, “Rochester’ appeared with ‘Mistah Benny” in a motion picture – a picture in which he consumed just as footage as the star. The nation’s movie audiences rocked with mirth. So, it may well be that “Rochester” has given colored entertainers a new day and a new dignity on screen and radio.

The Radio Preservation Task Force’s efforts to expand our access to the riches of radio’s history will enable us to better understand the medium’s impact on a wide range of topics in American cultural history, even a forgotten film premiere in Harlem 75 years ago.

Melvin Ely, Adventures of Amos n Andy: A Social History of an American Phenomenon (1991).

Michele Hilmes, Hollywood and Broadcasting: From Radio to Cable (1999).

Michele Hilmes, Radio Voices: American Broadcasting 1922-1952 (1997).

“Rochester: A New Day,” California Eagle (April 24, 1941) p. 8.

“Schomburg Citations of 1940 Cover Wide Field,” Chicago Defender (Feb 15, 1941) p. 12.

“’Buck Benny Rides Again’ will have premiere at Victoria,” New Amsterdam News (April 13, 1940) p. 21.

“Harlem Agog over First World Premiere: ‘Rochester’ to be Seen in Stellar Role; NBC to broadcast affair over chain,” Atlanta Daily World (April 22 1940) p. 2.

“Harlem’s Reception for Rochester at Film Premiere Tue, will top all previous ones,” New Amsterdam News (April 20 1940) p. 20.

“New Yorkers all set for Rochester’s Film Premiere,” Chicago Defender (April 20, 1940) p. 20.