Monty Python’s Life of Brian, British Local Censorship, and the “Pythonesque”

Post by Kate Egan, Aberystwyth University, UK

This is the sixth installment in the ongoing “From Nottingham and Beyond” series, with contributions from faculty and alumni of the University of Nottingham’s Department of Culture, Film and Media. This week’s contributor, Kate Egan, completed her PhD in the department in 2005.

This is the sixth installment in the ongoing “From Nottingham and Beyond” series, with contributions from faculty and alumni of the University of Nottingham’s Department of Culture, Film and Media. This week’s contributor, Kate Egan, completed her PhD in the department in 2005.

In the last five years, there has been a new burst of research activity around British film censorship (Barber 2011; Kimber 2011; Kramer 2011; Simkin 2011; Lamberti 2012). Much of this work has benefitted, in terms of primary source material, from the recent opening up of the British Board of Film Classification’s files from the last century. This post illustrates what can be learned about the – to date – under-explored area of British local censorship through consultation of British film-related archives (the BBFC archive, as well as local newspaper resources at the British Library). I will focus here on the British local censorship history of a film, Monty Python’s Life of Brian (Terry Jones, 1979), that has been consistently lauded, by critics and audiences, as one of the best comedies of all time, but which was given extensive –possibly unprecedented – levels of coverage in the local British press in late 1979 and early 1980.

In August 1979, the BBFC decided to grant Life of Brian an AA certificate (suitable for age fourteen and over) without cuts, a decision made after the BBFC had obtained legal advice on whether the film might be legally blasphemous. This issue was of particular concern after the British publication Gay News was prosecuted for blasphemous libel in 1976, but the BBFC had received reassurance that Life of Brian was not blasphemous in a legal sense. Indeed, in a BBFC bulletin sent to local councils throughout Britain in early 1980, the BBFC defended and explained its decision in relation to the social role and license of comedy, noting that the film’s potential to induce “a degree of irreverent scepticism in its audience” was “surely permissible in a democratic society.”

According to documents in the BBFC archives, however, by mid-1980, eleven councils had banned Life of Brian from their constituencies, 28 had altered the film’s certificate from an AA to an X Certificate, and 62 had screened the film but eventually decided to uphold the BBFC’s AA certificate. Consequently, and as Sian Barber has illustrated in Censoring the 1970s (2011), this flurry of local activity, controversy and debate around Life of Brian led to the film becoming an illuminating test case for the effectiveness of local film censorship in the UK at the end of the 1970s.

Over the last five years, after consulting newspaper clippings in the Life of Brian file in the BBFC archives I’ve been searching for further local newspaper articles, news reports, editorials and readers’ letters from areas of the UK where the film was banned or considered for banning. This post draws on issues that have emerged from this initial research, relating to debates in five local newspapers in particular:

- The Harrogate Advertiser, which covered the process and reactions to the banning of the film unseen by Harrogate Council’s Film Selection Sub-Committee in November 1979;

- The South Wales Evening Post, which covered the banning of the film by Swansea City Council in February 1980;

- The Dudley Herald, which covered the process whereby the town’s Environmental Health committee watched the film and then upgraded it from an AA to an X certificate in February 1980 (ultimately leading it to be banned in Dudley, as the film’s distributor, CIC, refused to allow the film to be screened in localities where a change to the original BBFC certificate was requested);

- The Exeter Express and Echo, which covered the process whereby the film was viewed by the city council in March 1980, but then kept its certificate at an AA;

- The Thanet Times, which covered the process whereby the film (in Thanet and Margate in Kent) was first banned unseen by the council in December 1979, before having its AA certificate reinstated in February 1980.

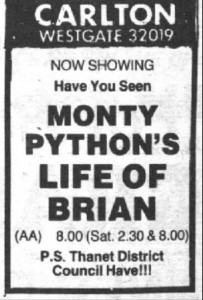

What comes through clearly when exploring these press debates is that the local controversies around the film could be seen – drawing on Annette Kuhn’s arguments in Cinema, Censorship and Sexuality (1988) – to have a number of productive consequences. Indeed, the local censorship fuss around the Life of Brian issue was hugely beneficial in generating heightened publicity for the film. Feeding into this was the fact that local people in areas where the film had been banned, or where it was likely to be banned, were organizing hired bus trips to adjacent areas where the film was being screened.  After the film was passed for screening in Exeter, for instance, the Exeter Express and Echo noted that screenings of the film in one Exeter cinema were attracting full houses every night and that the film was likely to run for fifteen weeks or more. The cinema’s manager attributed the crowds to the publicity the film had received and the consequent busloads of people coming to Exeter screenings from East Devon and Plymouth, where the film had been banned (April 24, 1980, p. 17). This also led, according to the Harrogate Advertiser, to the film being promoted in some areas as “the film that’s banned in Harrogate” (December 1, 1979, p. 3). In cinemas in the Thanet district, the film was promoted, after the initial council ban was overturned, with the slogan “Have you seen Monty Python’s Life of Brian – Thanet District Council Have!” (Thanet Times, June 17, 1980, p. 10).

After the film was passed for screening in Exeter, for instance, the Exeter Express and Echo noted that screenings of the film in one Exeter cinema were attracting full houses every night and that the film was likely to run for fifteen weeks or more. The cinema’s manager attributed the crowds to the publicity the film had received and the consequent busloads of people coming to Exeter screenings from East Devon and Plymouth, where the film had been banned (April 24, 1980, p. 17). This also led, according to the Harrogate Advertiser, to the film being promoted in some areas as “the film that’s banned in Harrogate” (December 1, 1979, p. 3). In cinemas in the Thanet district, the film was promoted, after the initial council ban was overturned, with the slogan “Have you seen Monty Python’s Life of Brian – Thanet District Council Have!” (Thanet Times, June 17, 1980, p. 10).

The local furor over Life of Brian had other kinds of productive consequences. It is evident, on analyzing local newspaper reports across the first half of 1980, that, while the initial debate related to the film’s potential to be seen as blasphemous or to offend those in the local community with strongly held religious convictions, ultimately the split between those who wanted to ban the film and those who opposed a ban was characterized, in the local press, as a split between the old and out-of-touch and the young and cine-literate. Consequently, the decision to ban Life of Brian unseen in areas such as Harrogate was deemed – by the local newspaper, certain councillors, and those writing to the newspaper to protest – as illustrating the outmoded, bureaucratic, archaic values of the council members who had the power to make such judgements on local public morals, values and taste relating to the cinema.

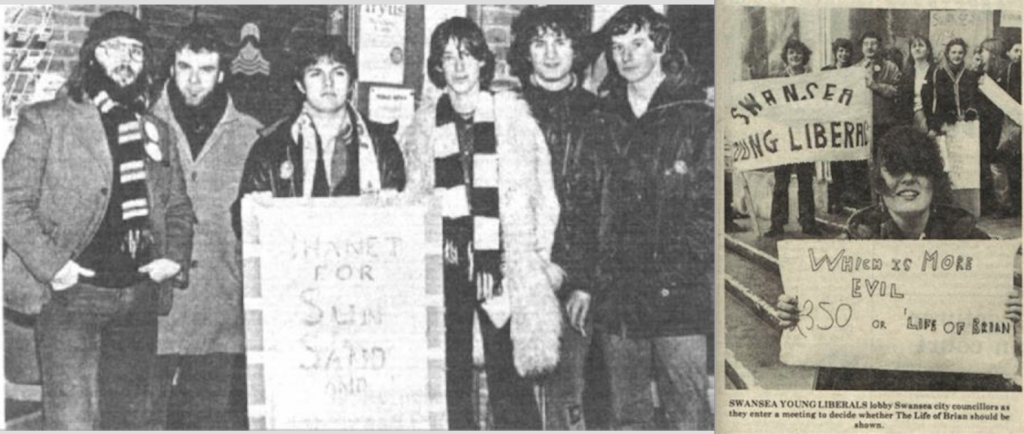

For a letter-writer in Dudley, the council had shown, through its decision, that it was “out of touch with the needs of teenagers” (Dudley Herald, February 22, 1980), while in a Harrogate Advertiser report, a teacher in Harrogate noted that the local ban had aroused resentment among “quite serious and intellectual sixth formers in Harrogate” (March 22, 1980, p. 1). Indeed, what is particularly revealing about this old/young split in the Life of Brian debate was that local young people’s protests against local councils tended to cross religious and political lines. According to the Thanet Times, for instance, the group (pictured below left) protesting against the council ban on the film included the chairmen of, respectively, the local Young Conservative and Young Socialist groups (January 22, 1980, p. 1), while this picture (below right) shows Swansea’s young liberals protesting the Life of Brian ban outside Swansea City Council (February 19, 1980, p. 3). In addition, the Dudley Herald published a letter from a Dudley West Young Conservatives representative, who noted that they had formed their own protest group against the ban, with the name SPAM: Society for the Prevention of the Abolition of Monty.

Also revealing is the way local press reports draw on a form of Pythonesque humor as a resource to highlight the anachronistic, undemocratic or bureaucratic nature of local council decisions. This humor manifests itself in two key ways. Monty Python is frequently used as a reference point to highlight the farcical nature of council decisions. For instance, in response to the news that Dudley Council’s decision to upgrade Life of Brian’s certificate to an X meant that the distributors would bar the film from being shown at all, a Dudley Herald editorial noted that the local saga around the film “had developed into a bigger farce than the film itself” (February 15, 1980, p. 4). The fact that the banning of the film locally had led many to go to see the film in other areas is also frequently related to Pythonesque humor. As one letter-writer noted in the Harrogate Advertiser, “perhaps the Committee could spend a little time conscience-searching and ask themselves how many of the young people who have travelled to other towns to see this film did so because of the excessive publicity given by their inept bungling of the whole issue. Monty Python would be highly amused” (February 23, 1980, p. 3).

A second tactic was to write letters to local newspapers in the Pythonesque satirical mode of, to quote Marcia Landy, a “disgruntled, morally offended patron.”[1] For instance, a letter to the Harrogate Advertiser noted that “I write in praise of our great and good councillors for their splendid and timely action in banning Monty Python’s Life of Brian. Not since the Emperor Nero has such a threat been posed against Christianity as presented by this film, which I have not actually seen. There is no doubt that, were it to be shown in Harrogate, Christian Civilisation as we know it would vanish overnight, old ladies would be sold to white slavers, there would be human sacrifice on the Stray, and blood-crazed mobs of perverted young people would burn our churches to the ground. Only the brave action of our council, which knows what is best for us, has saved our community from universal chaos” (November 24, 1979, p. 12).

In terms of the impact of such tactics, as the local furor around the film began to die down in July 1980, the BBFC sent a letter to all local councils expressing concerns about what the issue had revealed about the UK’s local censorship system. In 1979, the Williams Committee report on Obscenity and Film Censorship had proposed the scrapping of local authority censorship powers in Britain (a news item subsequently debated at length by the local newspapers I’ve consulted). This illustrates the way local protests about ill-informed, out-of-touch councillors, and the use of Pythonesque humor to pinpoint their ineffectiveness and inefficiency, impacted on national conceptions of the local censorship process at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s.

In Marcia Landy’s discussion of Monty Python’s cult status, she notes that Monty Python’s Flying Circus had “used television […] to satirize […] social institutions,” including “the state’s administration of social life,” and that this had occurred at a time, the late 1960s, “of worldwide cultural transformation, opening the door to critical approaches to authority and to gendered, generational, sexual, national and regional identity.”[2] In this sense, the processes and events I’ve outlined illustrate how the Python members themselves – and their role in providing tools for the critique of systems of authority, established thought and their potential hypocrisies – performed a crucial social and political function for protestors of the Life of Brian ban throughout the UK at this time.

[1] Marcia Landy, “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” in David Lavery (ed.), The Essential Cult TV Reader (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010), p. 172.

[2] Ibid., pp. 166-167.

Excellent research and a great piece. It’s odd to imagine now how any Python material was ever censored, especially LIFE OF BRIAN. This scuffle reminds me of JABBERWOCKY’s release in the States. In 1977, Dallas Texas had one of the few local censorship boards left in the US–and they put JABBERWOCKY in a special category that required viewers to be 17 (rather than 13 everywhere else). Not yet 17, I was prepared to burn down City Hall.