You Ever Hear of a Girl Detective?: Negotiating Gender and Authority in Candy Matson

The view from Telegraph Hill in San Francisco, where the character of Candy Matson lived in Candy Matson, YUkon 2-8209. Photo: Christoph Radtke

Post by Catherine Martin, Boston University

I recently spent some time going through the American Radio Archive’s Monty Masters collection to gather information for my dissertation on women in radio and television crime dramas. As I reviewed scripts for Masters’ female PI series, Candy Matson, YUkon 2-8209, I was struck by the number of edits relating to place and street names: more than any other radio series I’ve encountered, Candy’s writers appear to have been dedicated to getting San Francisco’s geography right. Of course, this might have simply been a product of the series’ production environment. Candy Matson, which ran on NBC’s West Coast network from June 1949 to May 1951, was broadcast from San Francisco in a period when most West Coast radio production was consolidating in Los Angeles. The locally popular series frequently emphasizes its regional affiliations, with Candy (voiced by Natalie Parks Masters) traveling up and down the West Coast and solving crimes from Los Angeles to Puget Sound (where she almost dies in a sabotaged seaplane). At home in her city of San Francisco, she surveys the urban space from the bay window of her Telegraph Hill penthouse and zips between neighborhoods in her flashy convertible. However, it is more likely that such attention to urban detail was meant to establish and strengthen Candy’s precarious authority as a radio private eye who also happened to be a woman.

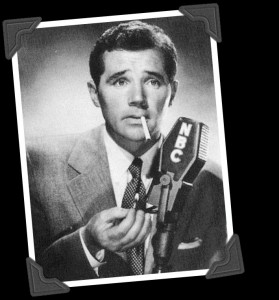

Howard Duff, who played private detective Sam Spade in The Radio Adventures of Sam Spade.

Candy Matson is not the only radio detective series concerned with emphasizing the detective’s intimate knowledge of the city. I’ve previously argued that The Adventures of Sam Spade (1946-1951, ABC/CBS/NBC) used Sam’s knowledge of San Francisco to assert his authority to interpret the urban space for increasingly suburban post-war radio audiences [1]. His conversational style of narration encourages audiences to see the city through his eyes, and his attention to detail asserts the intimacy of his urban knowledge and contributes to the urban atmosphere that pervades radio private eye series. Candy also navigates the city with ease, driving herself from place to place in a convertible, like a true Californian. From her penthouse on Telegraph Hill, she heads down the hill to visit her friend and sidekick Rembrandt Watson, downtown to call on Inspector Ray Mallard at San Francisco’s Hall of Justice, or across any of the city’s numerous bridges to explore the broader Bay Area. Significantly, Candy maintains a sense of control and power by insisting on driving herself, commenting that “I feel much better when I’m driving,” especially when traveling with strange men on cases because “there are a lot of forward passes that fall incomplete when a lady is driving” [2]. Candy even drives when she travels with trusted male friends like Watson or Mallard, showing off her knowledge of shortcuts, scenic routes, and obscure swimming holes along the Sacramento River, and cementing her claims to the special knowledge about people and places that makes the private eye an urban expert.

Candy’s claims to this urban (and suburban) expertise are especially important given her position as a female private eye in post-World War II America. As scholars like Jessica Weiss (2000) and Wini Breines (1992) have pointed out, postwar popular culture was filled with mixed messages about women’s roles and abilities, simultaneously promising them that they enjoyed equality with men and pushing them to find ultimate fulfillment in the more traditionally feminine roles of wife and mother. While she was not the first lady detective on radio, Candy is certainly among the most hardboiled, a genre more typically associated with working class male detectives and readers. Creator Monty Masters originally wrote the role of Candy for himself, but cast his wife, Natalie Masters, when his mother-in-law suggested making the detective female. While the character remained daring and take-charge as a woman, the writers also worked to emphasize Candy’s femininity. Jack French (2002) reports that Masters changed the original audition script to emphasize a romance between Candy and Mallard, which continues throughout the series and culminates in their engagement and Candy’s retirement in the final episode, “Candy’s Last Case.” In addition to the romance that ties her safely to one man – unlike her male counterparts, who often enjoy multiple flirtations per episode – the announcer’s opening narrations emphasize Candy’s femininity and even undercut her independence, especially in early episodes. One such introduction goes:

“Like a little whodunit without too much gore? This is for you then. And here’s another thing—we’ve got a gal for a detective—not a guy with all muscle and no brain. She’s cute, too. Oh, and I’ll let you in on a little secret. She thinks she solves all the cases she works on. But she doesn’t—not quite. There happens to be a guy named Inspector Ray Mallard who pulls our gal out of tight spots.” [3]

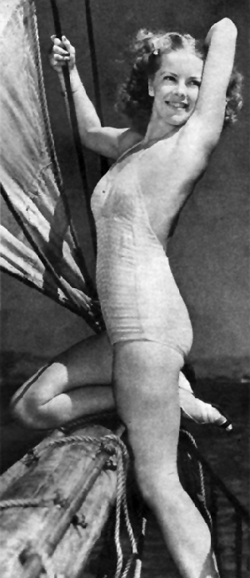

Others emphasize her blonde hair and compare her curves and “scenic effects” to Highway 101 [4]. Candy also frequently emphasizes her love for shopping.

Natalie Parks Masters, who played the female private investigator Candy Matson.

These contradictory emphases on Candy’s detective abilities and feminine appearance and dependence highlight her difficult position as a female PI who must struggle to be taken seriously, both by her clients and radio audiences at home. While she ultimately avoids the fate of so many female investigators on film, whom Philippa Gates (2011) argues went from enjoying progressive representations in the 1930s to becoming figures “of parody, passivity, or – by the 1950s – questionable sanity,” Candy has to continually prove that she is both a competent investigator and a normal woman – that she can still maintain feminine graces while taking on jobs that occasionally result in her getting knocked unconscious by a gunsel. The end result is unique and intriguing: a private eye program that presents ugly urban crimes without the seemingly requisite world-weary narrator. But despite this lack of the customary hardboiled gravitas, Candy continually resists categorization as a lightweight. She may be a former model, but she knows her city better than anyone and she insists on maintaining the power to navigate it. While she never managed to attract a commercial sponsor or make it to NBC’s national network, her popularity with West Coast audiences indicates that more than a few people were interested in stories about women working in atypical professions.

—

[1] Catherine Martin, “Re-Imagining the City: Contained Criminality in The Radio Adventures of Sam Spade.” Delivered at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference, Boston, MA, March 25, 2012.

[2] Candy Matson, YUkon 2-8209, July 21, 1949

[3] Candy Matson, YUkon 2-8209, July 14, 1949.

[4] Candy Matson, YUkon 2-8209, August 4, 1949.

“Gunsel” does not mean what you might think. And while SF might’ve had a few around, they’d be unlikely to show up in a radio drama produced in the early postwar years. (Hammett is using it in the correct sense when he has Sam Spade referring to Wilmer as a gunsel in “The Maltese Falcon,” but it is commonly misunderstood.)

Hi Roberta,

“Gunsel” actually did manage to sneak in every now and then. In this case, I was just using the term as shorthand for “a criminal/criminal lackey with a gun,” but it also pops up in series like “The Adventures of Sam Spade” – I’m guessing to play up the hardboiled atmosphere. I was just reading over the script for “Sam and the Corporation Murders” (one of the early ABC episodes) yesterday and Sam calls a pair of murderers “a couple of cheap gunsels.”

Thanks for reading!

Catherine