Call of Parental Duty: Advertising’s New Constructions of Video-Gaming Fathers

Post by Anthony Smith, University of Salford

This post continues the ongoing “From Nottingham and Beyond” series, with contributions from faculty and alumni of the University of Nottingham’s Department of Culture, Film and Media. This week’s contributor is Anthony Smith, who completed his PhD in the department in 2013.

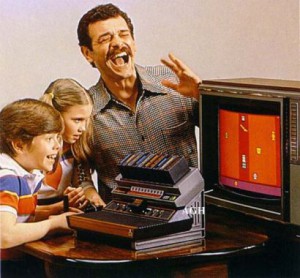

Advertisers’ use of family life as a means to market video games and hardware is by no means a new phenomenon. Hugely successful home consoles such as the Atari 2600 (launched in 1977) and the Nintendo Wii (launched in 2006), for example, were each promoted in part on the basis of the familial unity each system encourages. Television commercial spots for these platforms promised fun gaming experiences that children, their parents and their grandparents could enjoy together in living rooms (see videos below).

With this post, however, I identify how advertisers have begun to construct via their campaigns an alternate, more ambiguous relationship between video gaming and family life. Whereas advertisers have previously depicted gaming as a unifying force for the family (or, as I detail below, an activity entirely unrelated to family), recent UK ad campaigns for the Sony PS4 video game console and for Virgin Media’s broadband service suggest that video gaming might in fact be an imperfect fit for the family. In particular, each campaign establishes the father figure who is required to balance familial responsibilities with a video-gaming pastime that excludes other family members.

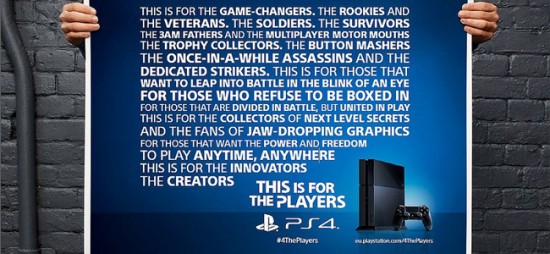

In the case of the PS4’s marketing, the discursive construction of this figure–who we might term “gamer dad”–emerged as part of Sony PlayStation Europe’s promotional campaign for the device’s launch in 2013, central to which was the assurance that this system “is for the players.” This marketing tactic helped Sony appeal to dedicated video-game players–a group that largely comprises the “early-adopter” market for home consoles, simultaneously positioning the PS4 against the rival Microsoft console (Xbox One, also launched 2013), which in contrast was initially promoted on the basis of its Skype and voice-activated TV-viewing capabilities. Sony’s poster and TV ad campaign further articulated who it envisaged these “players” to be: the PS4 serves, among others, the “rookies and the veterans. The soldiers. The survivors. The 3 am fathers and the multiplayer motor mouths. The trophy collectors. […] The once-in-a-while assassins” and “Fans of jaw-dropping graphics.”

“The players” that Sony’s marketing discursively constructs via these labels largely conform to an enduring stereotype of the “hardcore” gamer; that is, a player who is abrasively competitive (trophy-collecting, motormouth, multiplaying), prioritizes hardware that delivers strong technical performances (“jaw-dropping graphics”), and who favors games that feature fictional killing as a game-world objective (“once-in-a-while assassins”) and–more specifically–games concerning military warfare fictions (“The rookies and the veterans. The soldiers”), such as those of the Call of Duty and Battlefield first-person-shooter (FPS) series.

The marketing of console hardware more generally typically presents this “hardcore” gamer type as an adult male who, apparently without family, has free reign of the living room television (as is the case with the Aaron Paul-starring Xbox One commercial below).

Sony’s “3 am fathers” label, however, presents an unusual version of this type. The “3 am father,” the label implies, is required to pursue his gaming hobby in the morning’s early hours due to the prioritization within the day and evening of his familial and parental role, outside of which his hobby must exist. The label’s further implication is that the “3 am father” plays games that are incompatible with family life, such as violence-depicting FPS games, hence the need for their confinement to the twilight hours.

A Virgin Media commercial spot designed to promote its broadband service similarly constructs the image of a father figure who imperfectly incorporates the playing of “hardcore” video games into a familial context. The ad depicts “Nick,” an anthropomorphized seal on a living room couch, playing a militaristic FPS (Nick is a Navy Seal, apparently). The ad’s voiceover claims Virgin Media’s “superfast fiber broadband […] lets [Nick] download new games quicker,” which is, the voice-over informs, an essential feature for Nick “because every second counts when you’re not being a dad.” The ad subsequently reinforces this point, as the return of Nick’s wife and daughter to the home results in the interruption of his gaming session (see video below).

In line with the “3 am fathers” label, the Virgin Media ad suggests that a chief characteristic of “gamer dad” is the manner in which he must awkwardly situate his “hardcore” gaming hobby around his family’s requirements.

The advertising construct of “gamer dad” has the potential to be considered in relation to wider debates regarding media representations of video-game players, and more specifically players of “hardcore” games. In particular, “gamer dad” can be connected to the more general process within media culture of gendering “hardcore” gaming as a primarily male pursuit. A further component of Sony’s “This is for the players” promotional campaign, a video in which various men and women self-identify the types of players they are (see below), emphasizes this point.

The video at least to some extent avoids gendering tendencies, as it features, for example, a young woman self-identifying as an enthusiast of the FPS series Killzone. However, the apparent characteristics of the video’s one self-identifying mother are largely in opposition to those of the “3 am father,” suggesting that, for parents at least, conventional gender stereotyping continues with regard to representations of “hardcore” video-game players. “I’m a mum who plays with her son,” the woman says to the camera while holding up a placard stating her preference for Skylanders, a child-targeted game series. By suggesting that carrying out parental activities (such as playing Skylanders alongside a son) is the primary and legitimate means by which mothers achieve pleasure, Sony’s promotional campaign aligns mums with the “good mother” stereotype, of which feminists have been highly critical. Thus, while, advertisers make clear that the likes of Nick the Navy Seal and “the 3 am fathers” enjoy and are suited to game-world soldiering and assassinating (as long as such escapades are appropriately cordoned off from family life), they neglect to suggest also that mothers might desire–or can legitimately undertake–such recreational activities.