Mediating the Past: Mad Men’s Sophisticated Weekly Get Together

**This is the first in our new series: Mediating the Past, which focuses on how the past is produced, constructed, distributed, branded and received through various media.

About six months before Mad Men’s very first episode takes place, Hugh Hefner debuted a syndicated television program entitled Playboy’s Penthouse. It was an early example of intra-corporate cross-media promotion, in which—to invoke the era’s term of art and Hefner’s actual words—the “foremost exponent of sick humor.” Lenny Bruce, explained “I would never satirize the obvious,” before wondering aloud, on the program, who would advertise on such a program. Bruce concluded his ad-libbed ruminations by gibing Hefner directly: “I’m glad you’ve got some guts…you’re not interested in the people that don’t have any money.”

Maybe it was the mise-en-scène, but I recalled this line again during the extended swinging penthouse party sequence in Mad Men‘s fifth season premiere episode (of an apparently contractually finalized seven). Back with new episodes after 17 months, the media saturation leading up to its return has had me thinking that Mad Men and the cable channel AMC on which it is shown have “got some guts” in rather the way Bruce meant.

Maybe it was the mise-en-scène, but I recalled this line again during the extended swinging penthouse party sequence in Mad Men‘s fifth season premiere episode (of an apparently contractually finalized seven). Back with new episodes after 17 months, the media saturation leading up to its return has had me thinking that Mad Men and the cable channel AMC on which it is shown have “got some guts” in rather the way Bruce meant.

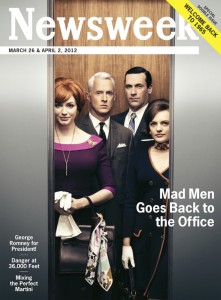

For a couple months now, middlebrow America has been utterly awash in Mad Men. The New York Times ran so many profiles, interviews, style pieces, analyses, reflections, recaps, think-pieces, reviews, political tie-ins, beverage tie-ins, and other pieces, that another media reporter, Joe Flint (@JBflint), tweeted after the season premiere ratings were revealed: “Mad Men draws 3.5 million viewers. I didn’t know NYT’s staff was that big.” The Washington Post meanwhile actually ran a piece on the number of Mad Men pieces it ran leading up to the season premiere: 22 including that piece itself! Newsweek contrived a special retro issue timed to correspond with the new season’s premiere. The New Yorker offers online readers weekly episode synopses, as does Slate, Salon and Esquire (which also lists “all things Mad Men” on its site, and sprinkles its hard copy pages with regular think pieces about the show it has suggested “is the greatest piece of sustained television ever made“). Even nominally non-commercial public service network National Public Radio ran stories about Mad Men on “Fresh Air,” “Morning Edition,” “Weekend Edition,” “All Things Considered,” it’s online food blog, and “Fresh Air” again! For certain media consumers, Mad Men has been impossible to ignore. Have you been hailed by Mad Men? (hint: you’re halfway through another piece about it).

For a couple months now, middlebrow America has been utterly awash in Mad Men. The New York Times ran so many profiles, interviews, style pieces, analyses, reflections, recaps, think-pieces, reviews, political tie-ins, beverage tie-ins, and other pieces, that another media reporter, Joe Flint (@JBflint), tweeted after the season premiere ratings were revealed: “Mad Men draws 3.5 million viewers. I didn’t know NYT’s staff was that big.” The Washington Post meanwhile actually ran a piece on the number of Mad Men pieces it ran leading up to the season premiere: 22 including that piece itself! Newsweek contrived a special retro issue timed to correspond with the new season’s premiere. The New Yorker offers online readers weekly episode synopses, as does Slate, Salon and Esquire (which also lists “all things Mad Men” on its site, and sprinkles its hard copy pages with regular think pieces about the show it has suggested “is the greatest piece of sustained television ever made“). Even nominally non-commercial public service network National Public Radio ran stories about Mad Men on “Fresh Air,” “Morning Edition,” “Weekend Edition,” “All Things Considered,” it’s online food blog, and “Fresh Air” again! For certain media consumers, Mad Men has been impossible to ignore. Have you been hailed by Mad Men? (hint: you’re halfway through another piece about it).

While this media surge contributed to this season’s premiere becoming Mad Men’s highest rated episode ever, ratings are not really the point (it still had 5.5 million fewer viewers than AMC’s The Walking Dead finale had the week before). Mad Men brings other kinds of value to AMC: the wealthiest viewers on cable, industry prestige (AMC Networks promotes itself with Mad Men’s four consecutive Emmys and three Golden Globes), and overwhelming (and overwhelmingly positive) media coverage. Mad Men, in other words, sustains AMC’s brand, providing a specific and prestigious visibility that extends beyond those who actually watch. Visibility like this matters for attracting more viewers, for setting ad rates, for attracting “quality” program producers, but also, crucially for a cable channel, for negotiating with MSOs and setting carriage fees. (It also helps Lionsgate continue to “monetize” Mad Men beyond AMC).

Branding for AMC is all the more important as it transitions within a changing television industry. Begun in 1984 to monetize vaults of otherwise unseen old movies, this is no longer seen as the most profitable way to use a library of films much less a branded cable channel. As AMC sought to expand its revenue (beyond cable carriage fees) by introducing commercials, it began to alter its programming to attract audiences of the type (younger, richer) and size (bigger) advertisers would pay for. In an era when old movie libraries are now more profitably being licensed to Netflix, Amazon, and iTunes, however, AMC has had to accelerate its rebranding efforts around a significant transformation (which is why “AMC” no longer stands for “American Movie Classics”) without the loss of its most valuable asset, a predominately male audience achieved through non-sports programming. This audience came to AMC for the Three Stooges marathons and old Westerns. They’ve been asked to stay for Mad Men.

Branding for AMC is all the more important as it transitions within a changing television industry. Begun in 1984 to monetize vaults of otherwise unseen old movies, this is no longer seen as the most profitable way to use a library of films much less a branded cable channel. As AMC sought to expand its revenue (beyond cable carriage fees) by introducing commercials, it began to alter its programming to attract audiences of the type (younger, richer) and size (bigger) advertisers would pay for. In an era when old movie libraries are now more profitably being licensed to Netflix, Amazon, and iTunes, however, AMC has had to accelerate its rebranding efforts around a significant transformation (which is why “AMC” no longer stands for “American Movie Classics”) without the loss of its most valuable asset, a predominately male audience achieved through non-sports programming. This audience came to AMC for the Three Stooges marathons and old Westerns. They’ve been asked to stay for Mad Men.

Actually, not even so much for Mad Men, but for what Mad Men says about AMC, what its presence reflects about the channel. Set in the milieu of mid-century advertising, it is itself functioning as an advertisement for a channel once associated with mid-century movies and now deriving increasing revenue from advertisements. Offering viewers the opportunity to feel simultaneously nostalgic for and superior to a version of an earlier era, Mad Men actually achieves something close to what Hugh Hefner only aspired to for his 1959 program, a “sophisticated weekly get together of the people we dig and who dig us.” If “sophisticated” once again means straight white sex, smoking, booze, and terse conversation, Mad Men at least presents it in ways that feel comparatively and flatteringly grown up for television today. Rather than zombie walkers and fidelity to a comic book, Mad Men offers well-dressed Manhattanite drinkers and fidelity to the style of an era. Middlebrow media has not been voluntarily filled with stories on the characters’ inner lives, much less the fashion, style, and recipes of the higher-rated The Walking Dead. HBO’s hits Game of Thrones and Boardwalk Empire (never mind Mad Men‘s other timeslot competition The Good Wife) have not had their own tabs on The New Yorker website. But Mad Men has. It was born to help rebrand AMC. It lives on to embody and advertise that new brand’s meaning. In this capacity it is meant for viewers, sure, but it is almost perfectly suited to attract and flatter the imaginations of advertisers, reporters, and the mediasphere more generally. The show’s value is not entirely dependent upon its immediate ratings. This is a point lost on would-be imitators like ABC’s Pan Am and NBC’s Hefner-endorsed The Playboy Club, but it is critical to making a show set in the past point to the future of television. It has got some guts.

This branding issues and media blitz is also key to Mad Men’s broadcast in the UK.

The satellite broadcaster BSkyB significantly outbid the BBC’s high brow digital channel BBC4 after 4 seasons in a deal thought to be worth over £5million. Mad Men (and shots of Joan’s behind in the two-way mirror) was a key part of the promotion of Sky’s new Sky Atlantic channel whose brand identity was built around an exclusive deal to show HBO programming, as well as Mad Men, even though the deal for the 5th season had still not been made between Weiner and AMC. Sky Atlantic is part of Sky’s bid to court the upmarket audience – often stubborn Sky refuseniks – with Quality television.

However many felt that Sky had overbid for MM, with estimates that it outbid BBC4 by x3 (there is a long history of antagonism between the BBC and part-Newscorp-owned Sky). The show’s BBC4 broadcasts averaged only 350,000 viewers, despite massive broadsheet coverage. Running up to S5’s UK debut, there was blanket coverage in the UK broadsheets and magazines. However, its premiere got 98,000 viewers, dropping to 47,000 by its 3rd episode – in comparison, Game of Thrones got more than 500,000 viewers. There was much joking on twitter – mirroring your NYT comment – that there was a MM article for every one of its Sky viewers. Sky claim that the premiere’s ratings is commensurate with MM s4 ratings in Sky homes, but surely the aim was to _increase_ viewers and subscribers.

Sky sought to utilise the brand of Mad Men, along with HBO (I would think many Brits assume MM comes from HBO) to shift the identity of the company amongst upmarket demographics away from sports, movies and Murdoch. No doubt downloads and repeats will increase that rating point and the cache of having Mad Men is strong. But it seems that they underestimated the size of the venn diagram crossover between Mad Men fans and broadsheet Murdoch-hating Sky refuseniks. I wonder how far up the illegal streaming/download charts Mad Men will rise as a result.

A very interesting piece about Mad Men and AMC! This has got me thinking about the other programs on AMC and how they are marketed. As a current Graduate Student in a Critical Media Studies program, most of my cohort is quite familiar with the AMC programs. We’re not exactly the middlebrow that media has been targeting with the wash of Mad Men articles, but we were informed of the return of the show more so by word-of-mouth and internet research (but can’t deny the ad campaigns as well). The same can be said for Breaking Bad and The Walking Dead, which often come up in our class discussions along with Mad Men. However, the point I’d like to make is that these serialized dramas on the premium (HBO, Showtime) and cable networks seem, to me, to be based more on the word-of-mouth advertising that could be classified as an evolution the “water cooler” show, because of the way that we are watching these revolutionary series.

Most of AMC’s, and some of the premium networks’, serialized programs exist online in one form or another, typically in a form where monetary payment is required (i.e. Netflix or HBO Go). Seriality is nothing new in the televisual medium, but it is particularly important with the advent of streaming because with the demographic (my demographic) that AMC is trying to address, being “in” on these “quality” programs is often part of being accepted into certain cliques or social circles, such as the work place or school. AMC has very cleverly planted their shows on these streaming services so that the tech-savvy demographic who are not “in” on these series can catch up and fit in with the crowd. Even after 4 seasons have aired, this is allowing tons of new viewers the chance to catch up on tens of hours of programming. ABC’s Lost unfortunately (or not? Think about the DVD sales…) was not able to capitalize on the streaming services, but it is interesting to think about how much bigger of a phenomenon that could have been if it had Netflix and Hulu to support it in its earlier seasons. I would be curious to see how much the number of viewers for the AMC series increased after they were all put on Netflix.