Comic-Con: The Fan Convention as Industry Space, Part 2

After a hectic five days in San Diego, I’ve experienced far more than I could ever recount here. Besides, exhaustive coverage of Comic-Con content is available all over the Internet. As I outlined in my previous post, my interests center on the industry presence at Comic-Con. With that in mind, this post focuses on one particular space, Hall H, in order to examine how the industry exerts its significant and formative power at Comic-Con as part and parcel of exclusive opportunities and rewards for fans.

Hall H is a cavernous, airplane hanger-like room at the east end of the convention center. Seating up to 6500 attendees, the room hosts panels dedicated to promoting Hollywood films, particularly blockbuster tentpoles and franchises. This year, the list of star-studded sneak previews included Ender’s Game, The Amazing Spiderman 2, Godzilla, Hunger Games: Catching Fire, X-Men: Days of Future Past, the Thor and Captain America sequels, and surprise announcements from Warner Brothers and Marvel and about the immanent team up of Superman and Batman and the title (and villain) of the next Avengers film.

Hall H is a cavernous, airplane hanger-like room at the east end of the convention center. Seating up to 6500 attendees, the room hosts panels dedicated to promoting Hollywood films, particularly blockbuster tentpoles and franchises. This year, the list of star-studded sneak previews included Ender’s Game, The Amazing Spiderman 2, Godzilla, Hunger Games: Catching Fire, X-Men: Days of Future Past, the Thor and Captain America sequels, and surprise announcements from Warner Brothers and Marvel and about the immanent team up of Superman and Batman and the title (and villain) of the next Avengers film.

The process of gaining access to the massive hall is daunting. Every year, an increasing number of attendees line up overnight. I spent Friday and Saturday in the hall and arrived between 4:30 and 5am on both days. I waited in line over five hours before the room was loaded (a process taking roughly an hour), and once admitted, I managed to find a seat towards the back of the room.

The line itself demonstrates the significant power and draw of industry promotion at Comic-Con as the spectacle (and labor) of attendees waiting in line produces an increased sense of value around studios’ promotional content. Contextualized as exclusive to Comic-Con, these advertising paratexts are distinguished from the more mundane, mediated promotion we encounter in our daily lives. The line helps to construct this distinction by providing visible evidence of attendees’ belief that this content is worth waiting for (on both days I sat in Hall H, attendees participating in Q&A sessions professed to the panelists that the wait had been well worth it). In order to participate in these kinds of exclusive opportunities, attendees must consent not only to the significant wait, but also to the maintenance of order and regulations–first, in the line, then, within the Hall. The process of queuing, then, transforms attendees into docile bodies, who wait patiently and compliantly for the panels in the hall.

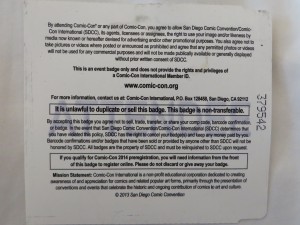

Two co-existing rules inform Comic-Con’s Hall H (and overall) experience, both of which are printed directly on the Comic-Con badge . First, attendees must consent to being photographed or recorded at any time and to give “Comic-Con, its agents, licensees, or assignees” the right to use their likeness for “promotional purposes.” Second, attendees must agree not to photograph or record any prohibited material and must obtain Comic-Con’s consent for the commercial use of “permitted” photographs and recordings. I learned about both of these rules firsthand when I recorded the introduction to the Warner Brothers and Legendary Pictures panel on Saturday.

The first half of this video demonstrates the interesting phrasing of piracy warnings in Hall H. Fans can record and disseminate everything but the studio’s footage. This rule works to preserve the proprietary property of the studios, while suggesting that attendees should see their experiences as similarly proprietary, an exclusive reward for their own effort and commitment after a long night in line. Optimally, attendees will “promote” their experiences in the same way that the industry promotes their products, by carefully controlling the dissemination of information. The studios, in retaining control of their footage, also get to decide where and how it will be unveiled online, which sometimes happens simultaneously or shortly after it is screened in Hall H. Effectively, the exclusive atmosphere of Hall H, both in terms of the restrictions around filming and sharing of content, and the excitement associated with being among the first to see and the first to know, makes Comic-Con attendees into an unpaid promotional army, enthusiastically reproducing their exclusive experiences for a larger collection of consumers online and on social networks.

Though it is difficult to see in the darkened room, the second half of this video captures the moment when two large curtains drop to reveal 180 degrees of screens, a Hall H technological spectacular first introduced by Warner Brothers in 2012. The video ends when a member of security approaches behind my seat and tells me not to record anything on the screens. This is, of course, absurd, as the content on the screen in that moment is a widely disseminated and familiar corporate logo. Whether this warning reflects an accurate enforcement of the regulations or an overzealous member of security, it demonstrates just how little control one has as a member of the Hall H audience. Either comply, or be ejected.

Later, during a panel for 20th Century Fox, the moderator excitedly informed the audience that we were all going to be photographed by a company called Crowdzilla, and that the photograph would be so detailed that we would be able to locate and tag ourselves on the X-Men Facebook page. Alongside the troubling and invasive implications of the Crowdzilla technology, this stunt invites the audience’s implicit consent to be photographed for promotional purposes (the first rule listed on the Comic-Con badge). Framed as a fun, novel, and innocuous addition to the Hall H experience, this stunt further exploits the spectacle of the Comic-Con crowd as a vehicle for marketing purposes. This example demonstrates a dual function of Comic-Con: on the surface, the event operates as a location for studios to market to a core audience of fans, but in the process, these same fans become part of a larger marketing paratext.

In addition to demonstrating how studios interpellate Comic-Con attendees as unpaid promotional laborers, the lines, the piracy warning, my experience with security, and the Crowdzilla stunt also suggest a deeper, ideological power imbalance in the relationship between media industries and attendees at Comic-Con. If a corporation’s logo operates as a of signifier of its identity (however problematic that identity may be), in Hall H, these kinds of identities are protected and privileged, while individual attendees must hand those same rights over to studios and Comic-Con organizers. The pleasures of consuming paratexts at Comic-Con are the pretense through which studios assemble a crowd that functions more usefully as a group of indistinct “fans” than as discreet individuals. In this way, my experiences in Hall H suggest a troubling hierarchy underpinning Hollywood’s presence at Comic-Con, a hierarchy that, as the Veronica Mars Kickstarter campaign suggests, extends to the relationship between media industries and fans more generally. Instead of simply playing the role of media consumers, this audience is incorporated into a hierarchy of industry production and promotion, geared towards meeting the studio’s marketing goals. The configuration of Hall H, with studio representatives elevated and isolated on a stage before a crowd of 6500 attendees, manifests these hierarchies in real space, rendering them highly material, and by extension, visible for five days a year.

Thank you so much for writing about your experience at SDCC! I was there as well and found it an equally fascinating moment of industry self-representation. I didn’t make it into Hall H, but spent some time in Ballroom 20, which also required hours in line.

I agree with many of the conclusions you draw here regarding the industry’s engagement and solicitation of fan’s investment/labor, but I think there’s also another side to this. Fans rework these experiences and encounters with the industry—in other words, I think fans have some agency in these moments. Being in Hall H or camping out for it is not only about gaining excess to exclusive content, but is also a way to engage with fellow fans in line or to demonstrate that you are really serious about attending SDCC. The industry might have very specific goals for their fan engagement, but fans have their own goals and contexts for Hall H/SDCC that may or may not align with industry expectations. Speaking for my own decision to stand in line for hours to attend the Agents of SHIELD panel on Friday, I found the prospect of experiencing this panel in the company of 4,500 like-minded fans as significant as having access to the screening of the pilot.

I realize that Antenna’s word limit often means sacrificing additional ideas, so if you have/had any thoughts on how fans negotiate the positions assigned to them by the industry at SDCC, please share them in a comment.

Thanks, Melanie, for your excellent questions and insights. Indeed, there is a lot more to say about the agency and experiences of fans at conventions. In fact, Antenna has some scholars doing great work on that right now in their series of articles on LeakyCon in Portland, which seems to be a space occupied and significantly shaped by the kind of fan practices and experiences you’re describing.

What I’m suggesting through my analysis of Comic-Con, as a space heavily shaped and informed by the industry, is a critical compliment (I hope!) to those kinds of conversations about relationships in and between fandoms and the agency of individual fans. That is to say, although Comic-Con is experienced in many different ways (some of which work against the grain of industry expectations) by a vast array of individuals, the publicity machine that is also at work there isn’t necessarily invested in making those same distinctions. As coverage of the event moves through the Internet and mainstream media outlets, it is much less about the specificity of the fan experience and much more about how that experience functions in relation to the presence of the industry. Take, for example, the Agents of SHIELD panel: The value of your experience there was shaped by being surrounded by 4500 likeminded fans, but those 4500 bodies signify something very different for ABC, who might see that audience as a kind of tool for measuring responses to the pilot or creating more publicity for the show. In some ways, the material reality (the lines, the confusion, the differing investments) of fans and industry converging in spaces like Ballroom 20 and Hall H, or Comic-Con as a whole, gets collected and managed by the dominant discourse that emerges from the event, which is both a literal marketing discourse (coming from the industry itself) and a publicity discourse (coming from media coverage).

Another important distinction needs to be made, which is that the agency of fans isn’t automatically a good thing and the industry presence isn’t always bad. Take for example, the “Women Who Kick Ass” panel, planted smack dab in the middle of a day of massive promotion (WB’s Superman/Batman announcement in the morning and Marvel’s Avengers 2 teaser at the end of the day). On this panel, Michelle Q, Danai Gurira, Tatiana Maslany, Michelle Rodriguez, and Katee Sackhoff discussed with incredible rigor, candor, and critical thought, the state of women in the industry, their depiction in the media, and distinguished between these issues and specific problems facing women of color. In concluding, they called for fans and industry (particularly women) to be proactive in demanding and producing more and better representations. I think this represented the best and most positive of possibilities for the relationship between the industry and fans I’ve seen at Comic-Con to date. But throughout this entire panel, the lines at the bathroom and concession stand were long, people walked around the room, and the man sitting next to me speculated that the panel was strategically positioned midday in order to clear out Hall H between Warner Brothers and Marvel, so that more people could enter the room. At the end of the hour, a particularly unpleasant man a few rows up suggested an alternate title for the panel, calling out “Women Who Talk To Much.” I think this experience speaks to the danger of painting either the industry or fans with overly broad strokes (and harkens back to some of the gendered discontent about Twilight at Comic-Con). I totally agree that it would be inaccurate to suggest that everyone in that room has the same investments, positive or negative, and a lot more work needs to be done in order to understand how these investments converge and diverge. But I also think it demonstrates just how powerful and structured the expectations about Hall H have become, that a panel that diverged from pure promotion and aimed at productive discourse was the “break” between the “real” content: industry marketing.

Hopefully that (somewhat long-winded) answer addresses some of your questions… and I especially hope it raises more, as I think the issues you bring up are part of a really important conversation for scholars of fan and industry studies alike.