Negotiating Authorship: Showrunners on Twitter VI

To this point, my analysis of showrunners on Twitter has focused on exceptional circumstances defined by controversy or conflict. They have also focused on showrunners—Harmon, Sutter, Lawrence, Lindelof—who have translated their professional identities into tens or hundreds of thousands of followers, gaining fame—or infamy—for their social media presence.

To this point, my analysis of showrunners on Twitter has focused on exceptional circumstances defined by controversy or conflict. They have also focused on showrunners—Harmon, Sutter, Lawrence, Lindelof—who have translated their professional identities into tens or hundreds of thousands of followers, gaining fame—or infamy—for their social media presence.

However, while these showrunners and others like them have cultivated active and expansive social media profiles, the work of framing professional identity through Twitter is not reserved for the famous or infamous. While we can—and should—think of this in terms of below-the-line laborers, I also want to use this as an opportunity to explore the varied jobs under the “showrunner” umbrella. Although this title has become associated with those who create and subsequently shape the creative vision of a television series, showrunner also applies to the producers hired to “run” a show alongside its initial creator, laborers who are often less commonly associated with the rise of “showrunner” discourse within the industry.

Popular discourses on TV authorship have focused on figures like Matthew Weiner or Vince Gilligan who are decidedly “TV authors” in their control over the visions of their respective series. However, in the instance that the creator of a series lacks the experience, aptitude, or time necessary to fill the role of showrunner, more experienced writer/producers are brought in to shepherd the ship. While their labor is far from invisible, these showrunners are nonetheless unable to access certain authorship positions given that they are executing someone else’s vision, most often brought on after the pilot stage; similarly, those who created a series but are not serving the role of showrunner have limited access to discourses of authorship as the series moves forward. In the former case, although the rise of showrunner discourse has traditionally been associated with questions of authorship, here we see the day-to-day role of a showrunner imagined primarily through management, despite the fact that management involves considerable creative input; in the latter case, although creators maintain access to narratives of vision and creativity, they must also navigate the labor of those running the show day-to-day.

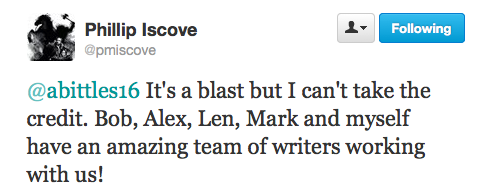

This reality reframes Twitter as a space where the respective roles of creators and “post-pilot showrunners” are negotiated. Fox’s Sleepy Hollow is the first credit for co-creator Phillip Iscove, who remains a supervising producer alongside showrunner Mark Goffman (The West Wing, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip). Both are on Twitter, and both engage and interact with fans from a position of authorship by answering questions or offering teases of future episodes. However, both consistently avoid claiming sole authorship over the series: in these similar tweets sent to fans, they each emphasize the collaborative nature of the series’ development, with neither having full access to the sole-authored television ideal we imagine when evoking terms like creator or showrunner.

Their careful deference to the other’s labor—and the labor of mega-producers Bob Orci, Alex Kurtzman, and Len Weisman—is a necessary trait when working in a situation like this one. John Wirth has become known for playing a part in such situations, recently stepping in as the post-pilot showrunner for Fox’s Terminator: Sarah Connor Chronicles and NBC’s The Cape. In a recent conversation, Wirth spoke of his experience working alongside creator Josh Friedman on Terminator: Sarah Connor Chronicles, and said “my job on that show was to help him make [his vision] happen, and fight all the studio battles and network battles on his behalf to promote his vision of the show.” At the same time, of course, Wirth was simultaneously contributing to his own professional identity, which this past year led AMC to hire Wirth to take over as showrunner on western Hell on Wheels for its third season.

Wirth’s experience on Hell on Wheels reinforces the need to consider the production culture surrounding showrunners on a case-by-case basis. While similar to Wirth’s past experience given that he is taking over a series created by someone else, the situation is unique in the complete absence of the original creators: Wirth is replacing the departing showrunner who previously worked alongside creators Joe and Tony Gayton, whose own contract on the series was not renewed after season two. As a result, although Wirth may not have created the series, he is not tied to someone else’s vision, and has access to sole authorship of its narrative direction moving forward in its recently completed third and upcoming fourth seasons.

An image Wirth shared from the set of Hell on Wheels, featuring series script supervisor Sabrina Paradis.

Wirth is not among the more active showrunners on Twitter, but it has nonetheless become a space—along with interviews like the one I conducted—where he can make these claims to authorship. He interacts with fans, tweets photos taken on the set in Calgary, Alberta, offers teases regarding his plans for the upcoming fourth season, and livetweeted Saturday night broadcasts of the series, all practices that are common among showrunners who have always been the sole creative vision behind a series. While these tweets serve a purpose as promotion for the series and as community-building exercises for the show’s fans, they also give Wirth to ability to separate his labor from discourses of management toward discourses of vision and creativity, a task that becomes easier without the need to defer to others’ labor.

As we head further into a period where showrunners engaging in self-disclosures through Twitter has become a common practice within the television industry, those self-disclosures are inevitably intersecting with parallel realities of the television industry. In the case of Iscove, Goffman, and Wirth, we are seeing existing, nuanced discourses of authorship functioning within the industry being reframed through social media practices not necessarily designed to communicate said nuance (unless we count the limited affordances of the biography section on Twitter, highlighted in the above image), requiring specific negotiation and investigation that will remain throughout the runs of their respective series.