Why Superhero Movies Suck, Part II

A still-unimpeachable authority offers the rest of his surely irrefutable hypothesis.[1]

Post by Mark Gallagher, University of Nottingham

This post continues the ongoing “From Nottingham and Beyond” series, with contributions from faculty and alumni of the University of Nottingham’s Department of Culture, Film and Media. This week’s contributor, Mark Gallagher, is an Associate Professor in the department. Today’s entry is the second installment in a two-part post, and resumes with the third point in a five-point diatribe. Part One of this two-part post appears here.

Avengers: Age of Ultron opens with a battle scene that recalls a comic-book splash page. But don’t be fooled.

3. As a magnet for fandom, superhero movies violate the implicit contract between producers and consumers. At the risk of bowing to nostalgia, I point to the letters pages of 1970s Marvel comics for their evidence of fan engagement and for editors’ own discursive efforts at artistic legitimation.

On one side, consider the hair-splitting response of one 1973 letter-writer to Marvel’s horror-fantasy series Creatures on the Loose, a fan distressed with the company’s depiction of obscure pulp-lit creation Thongor of Lemuria. (You know, THAT Thongor of Lemuria.) “Thongor just does not sound like the Thongor I know and love,” writes the aggrieved reader, Brian Earl Brown, before lavishing praise on the (soon-to-be-cancelled) series.

Fandom is of course about returns on investments of time in the form of (sub)cultural capital. Brown’s implied engagements with neo-pulp novelist Lin Carter‘s 1960s Thongor stories licenses him to judge the adaptation’s fidelity, and to weigh in subtly on transmedia style considerations (by noting the difficulty of adapting Carter’s “deceptively simple and lucid style”). Still, as purveyors of fantasy adventure, pulp fiction and comic books appear complementary textual forms, and both in the realm of low culture, hence the letter-writer’s concern with fidelity rather than legitimation.

Soon enough, though, readers and editors did take to the front lines (or at least comics’ letters pages) to argue for comics’ place in the landscape of art. Consider in this respect Marvel editors’ own sympathetic response (also in Creatures on the Loose, in early 1974) to another reader’s losing battle to legitimate his favored leisure form.

Addressing the letter-writer’s experiences of being “ridiculed, scorned, pitied” and more, Marvel’s editors note not only that “college courses in the literature of comics are springing up all over the country” but also, prophetically, that “filmmakers are studying the techniques” of then-prominent comics artists. Uh-oh.

Fast-forward 40 years, to the present. With the question of artistic legitimacy either resolved or simply abandoned—either way, think pieces about the merits of “graphic novels” appear less commonplace in the current climate than in the 1980s and 1990s heyday of Art Spiegelman‘s Maus (1991) and Joe Sacco‘s initial dispatches from war-ravaged Central Europe—mainstream comic books and their cinematic offshoots may now lack the fundamental transgressiveness that lent them vitality in the 1960s and beyond. Thanks to longstanding distribution practices, comics remain a fundamentally niche product. Recent digital-distribution initiatives notwithstanding, for the past thirty years in the U.S., serial comics have been sold only in specialty comic-book stores, limiting their readership to those people who set foot in such stores. Yet by serving up this niche commodity in adapted form to all four key quadrants of the filmgoing population, rights-holders Disney and Time Warner deplete the subcultural capital of their properties and their readerships.

4. Superhero movies relocate film-industry resources from more original material and siphon talent from richer projects. Many people involved in superhero films’ production are doing the best work they ever will, which is a compliment or insult depending on one’s judgment of the finished product.[2] Others—particularly actors given the visible evidence of their work—appear to be squandering their considerable talents. Mark Ruffalo may use his Avengers paychecks to bankroll his political activism and to appear in films that make greater demands of his craft, but his normally prolific output slows to a trickle in the Avengers films release years of 2012 and 2015.

Elizabeth Olsen delivered an impressive debut performance in Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011) but as the Avengers’ Scarlet Witch spends much of Age of Ultron frozen in a “I am casting a spell” pose (as she memorably demonstrated on a Daily Show appearance preceding the film’s release).

Scarlett Johansson has enjoyed a succession of compelling roles, but any bipedal runway model could just as well play her Black Widow character in the Iron Man and Avengers series given the role’s limited requirements. (#1: Look good in body-hugging outfit. #2: Talk sassy.) Is the sprawling Avengers franchise the price we pay to get Under the Skin (2013)? I hope not (but note to studios: please do give us another Under the Skin, even if you wouldn’t fund the first one).

Some actors—Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen in the X-Men films (2000-2014), and Robert Redford in last year’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier—have benefitted from scripting that allows them to, in a word, act. Perhaps no one loses if Jessica Alba’s work in the 2000s Fantastic Four films (2005, 2007) prevented her from making Into the Blue 2, but certainly many people with talents in front of and behind the camera turn down other film projects in favor of the high visibility (and possible residuals) of tentpole superhero films. (Sure, I know too the scientists who could be developing the next Internet are instead hard at work on iPhone fart-simulation apps, but still.) Even those whose performance styles suit the material well can be ill-served. The Iron Man role, for example, limits Robert Downey Jr. to vocal and facial performance in support of his body double or CGI avatar’s screen image. He’s skilled at both but is capable of much more.

5. Superhero movies pollute film discourse. Like Donald Trump’s Presidential candidacy, superhero movies appear a harmless diversion but actually refocus the cultural conversation in unproductive ways. As dreadful acronyms such as “MCU” and “Phase 3” (the latter meaning, “we’re determined to run this thing into the ground”) infiltrate entertainment discourse and popular consciousness, one might reasonably assume that superhero films represent some kind of high-water mark of contemporary cinema.

Many other high-calorie multiplex products occupy comparatively less intellectual real estate—the Transformers series (2007-2014), for example, does not excite viewers and commentators in the way recent superhero adaptations have done. To me, more than anything, a film such as The Avengers looks expensive. As a vehicle for directorial artistry, or acting talent, or narrative complexity—or for more expressly technical categories such as impressive cinematography, sound design and visual effects—it’s pretty unmemorable. Like most other Hollywood superhero films, its contribution to film economics is substantial, its contribution to film art is negligible, and its contribution to film culture is dare I say dispiriting.[3]

Make what you will of this lament from an aging white male who finds his cherished Rosebud replaced with a 160-horsepower Ski-Doo. And credit superhero films with managing to make even fare such as this summer’s Jurassic World—the “why not another one?” sequel to a calculated-blockbuster franchise that sprang to movie life in full bloat over two decades ago—appear fresh and original. But perhaps the violation I feel is instead resentment at receiving studio superhero behemoths at the wrong moment. After all, I thought Watchmen (2009) was one of the year’s best films—if the year was 1989. And Quentin Tarantino’s remarks in a New York magazine interview last month ring at least partly true for me:

I wish I didn’t have to wait until my 50s for this to be the dominant genre. Back in the ’80s, when movies sucked—I saw more movies then than I’d ever seen in my life, and the Hollywood bottom-line product was the worst it had been since the ’50s—that would have been a great time.

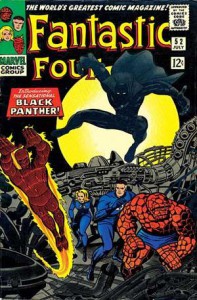

Still, this year, even de facto industry cheerleaders show signs of unrest. Media outlets trumpeting spotty opening-weekend performances for recent releases such as Ant-Man and Fantastic Four (both 2015) appear to exhibit exhaustion with the superhero phenomenon, and perhaps for oversized tentpole releases generally. As for me, I’ll start looking elsewhere for costumed characters onscreen, whether it’s the pleasingly ridiculous tussling models of Taylor Swift videos (de facto superheroines all, but sullying no previous creations), or better yet, the delirious art mutants who parade through Ryan Trecartin’s outlandish chamber dramas. Just keep me thousands of miles away from that Black Panther movie, because I like that character just fine in two dimensions, on yellowing newsprint.

[1] Preview of corrective coming attractions: for an international, and more level-headed, take on this trend in contemporary cinema, join us on September 24, when Nandana Bose contributes to this column with her analysis of recent Bollywood superhero films. For other recent, thoughtful takes on superhero films, head over to Deletion for its current “episode” on sci-fi blockbusters, and particularly to the entries from Liam Burke and Sean Cubitt.

[2] In this respect, I have only praise for the giant canvas afforded Sam Raimi for three Spider-Man films (2002-2007) and for Anthony and Joe Russo’s helming of Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) as a 70s-style conspiracy thriller.

[3] Consult the comments section of this link for raves about The Avengers‘ rumored $260 million budget, which for many fans translates into sure-fire “epic” quality.

You are such a great author. I can see your point clearly! Thanks for sharing this lovely article. By the way, what about super hero tv series, you know like The Flash from DC Comics? Will be lovely if you have review about that as well. Thank you!

Thanks for the comment, Desy. Regarding TV series, I chose not to cover those since my post was quite long already. Also, others at Antenna have done thoughtful reviews and analyses of series such as The Flash and Daredevil .

A number of thoughtful scholars weigh in on The Flash here:

/2014/10/09/fall-premieres-2014-the-cw/

And I’d recommend two posts from earlier this year on Daredevil as well, from Piers Britton and John Vanderhoef:

/2015/05/01/marvel-wired-daredevil-and-visual-branding-in-the-mcu/

/2015/04/21/devilish-partners-daredevil-netflix-and-exclusive-original-programming/