Reimagining Passions, Pleasures and Bad Lady Texts

Post by Kristen Warner, University of Alabama

A benefit of studying so-called bad feminine media objects is that the debates around poetics and quality are vacated leaving us to look at it however we would like. And while some are in the business of (rightly) reclaiming the beauty of the bad text, there’s something almost liberating about letting it be, immersing one’s self in that which seemingly disqualifies it from study. In the case of the category Elana Levine borders around “Passions” in her edited collection Cupcakes, Pinterest and Ladyporn: Feminized Popular Culture in the Early Twenty-First Century, the contributors all honed in on examining the pleasures women experience and navigate through commodified texts targeted to them. Levine’s instinct in putting these pieces in conversation with one another was spot-on in the realization that although all of the contributors analyzed different pieces of feminist media, the connecting tether among them was how they all explored how women used these texts to negotiate their own identities and desires in this post-feminist era.

Imagining that an affective response like pleasure that is not purely founded in celebration of a television show or a book series targeted to them but also in the joy that comes from critiquing those very texts is an act rarely allowed women in twenty-first century media. Our hot takes and think pieces easily reduce nuanced conversation down to simplistic binaries of “if this is good or bad for women” with the notion of a woman liking bad things as revolutionary.

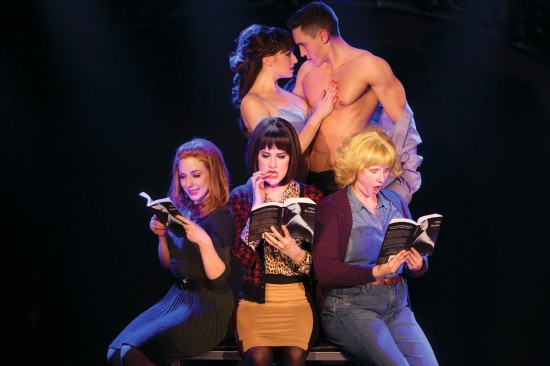

But what if women—all kinds of women—have been enjoying the bad all along? And what if, as posited by Melissa Click in her “Fifty Shades of Postfeminism: Contextualizing Readers’ Reflections on the Erotic Romance Series” chapter, the pleasure for women readers of this book franchise emerge after using this text to think through their own behaviors if allowed to imagine themselves as the heroines of this story?

I submit that the goal of the “Passions” category is to answer that very question. Jillian Baez’s “Television for All Women? Watching Lifetime’s Devious Maids,” maintains that depending on if the female viewer is Latina or white, the question of who they imagine themselves to be in the series generates a bifurcated set of pleasures. I like how Baez notes that, “while most female fans are watching Devious Maids as a source of feminine pleasure derived from its similarities to the generic qualities of Desperate Housewives, Latina fans view the series for its Latina cast and storylines that humanize female domestic workers.” Thus the joy for Latina audiences comes from these characters’ specificity as domestics who are also allowed these fantastical moments of power that transgress the servitude so many Latina women must navigate in their own lives.

Similarly, the piece I wrote, “ABC’s Scandal and Black Women’s Fandom,” takes up the question answering how black women identify with a black character also blurred between the stuff of fantasy and the bodily reality of a black woman enshrined in the spirit of colorblindness. The answer I explored was that through a process of gap-filling online labor from discursively making her hair a frequent topic of discussion to rewriting dialogue in the register of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and writing fanfiction around her being the object of desire between two powerful white men, black women fans are able to cultivate a more dimensional and culturally representative version of Olivia Pope.

The final point I make in the chapter ties to the work Erin A. Meyers writes in “Women, Gossip, and Celebrity Online: Celebrity Gossip Blogs as Feminized Popular Culture.” I end the chapter with a small discussion on a “real person” ship within the Scandal fandom—the Terrys (a portmanteau of the two leads Kerry Washington and Tony Goldwyn) and how while the desire around this couple is not wholly based in the need for them to be true but rather in how it helps some black female viewers to strategize ways to keep Washington at the center of the fandom. This coupling, largely the stuff of gossip, tethers to one of Meyers’ central tenets of the importance of gossip as communication: “Gossip is not simply the pursuit of truth. It is a process of narrativizing and judging the contrast between the public and private celebrity image as markers of larger social ideologies, particularly around gender, race, sexuality, and class. While such talk is not inherently resistant to dominant norms, the fact that it offers a space where women’s concerns are negotiated and made meaningful makes it, and celebrity culture, important sites of cultural analysis.” The pleasures of what it might mean for Goldwyn, a name that’s a part of Hollywood history to be coupled with Washington, a type that represents the best of black womanhood are more than can be expressed in this piece.

What’s more, Meyers’ article ties us back to Click’s contribution in that both describe the pleasures that accompany the ways women look at female celebrities in the same ways they may look at Anastasia Steele: models for who they may simultaneously want to be and also reject.

Women’s passion told through the lens of women’s pleasure is still in its infancy as an object of research. But I think the pieces here serve as a wonderful start in the study.