Our Intractable Ideological Moment: Surnow, The History Channel, and the Kennedys

For me, the dilemma began in 1991. I was teaching an “Introduction to Political Science” class at the time, and one evening I boldly proclaimed that what the new talk radio media phenomenon, Rush Limbaugh, was saying was a load of crap. I simply assumed that anyone attending college would, of course, recognize that Limbaugh’s spurious claims, ad hominem invective, and dubious social and political analysis would be obvious to any sentient human being. I was taken aback, though, when a round-faced young man on the front row from somewhere in rural Alabama earnestly and honestly proclaimed that I was wrong—Rush Limbaugh was not lying; he spoke the truth, I was told.

For me, the dilemma began in 1991. I was teaching an “Introduction to Political Science” class at the time, and one evening I boldly proclaimed that what the new talk radio media phenomenon, Rush Limbaugh, was saying was a load of crap. I simply assumed that anyone attending college would, of course, recognize that Limbaugh’s spurious claims, ad hominem invective, and dubious social and political analysis would be obvious to any sentient human being. I was taken aback, though, when a round-faced young man on the front row from somewhere in rural Alabama earnestly and honestly proclaimed that I was wrong—Rush Limbaugh was not lying; he spoke the truth, I was told.

Ever since that moment, I have wrestled with what I see as the fundamental issue that defines our political moment in time—the seemingly irreconcilable epistemology of liberals and conservatives. That is to say, conservatives have mobilized a full scale assault on our previously shared ways of knowing and what counts for truth. For at least two decades (if not longer) they have routinely promulgated a myth of an untrustworthy and dangerous “liberal media,” as well as “liberal elites” that supposedly dominate much of society. That has grown in recent years into a full-throated screed against any sector of society that doesn’t adhere to the orthodoxy of right-wing conservativism. While this line finds obvious currency in the rhetoric of media populists such as Sean Hannity, Glenn Beck, Bill O’Reilly, and Limbaugh, it is now much more pervasive through all segments of the Republican Party and conservative establishment, including politicians such as Sarah Palin, Michelle Bachmann, Eric Cantor, and others. Furthermore, it is now routinely a rallying cry for all ilk of ill-informed grassroots groups, including that amorphous yet dangerous grassroots populist uprising known as the Tea Baggers.

As I have argued elsewhere, what lies at the center of these attacks is an epistemological challenge to how society arrives at its truth claims. From the ridiculousness of Conservapedia (the right-wing’s answer to the supposedly liberal and anti-Christian Wikipedia) to the patently offensive assault on knowledge and history that is Glenn Beck’s “documentaries” linking Fascism and Hitler to Communism and Stalin (and by association, the great American Socialist Barack Obama), the far right is making headway in their promulgation that the old ways of arriving at knowledge are not to be trusted (a point parodied, of course, when Stephen Colbert noted that “reality has a well-known liberal bias”).

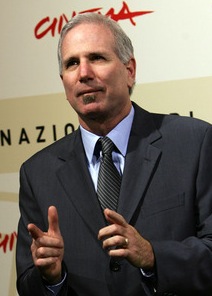

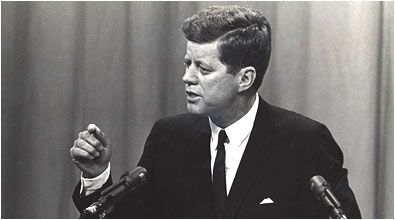

The latest flair-up in this epistemological challenge can be seen through Joel Surnow and The History Channel’s upcoming documentary on the Kennedys. Press accounts report that left-wing documentarian Robert Greenwald (Brave New Films) is spearheading a campaign to thwart what he and former Kennedy staffers see as a tawdry and malicious hatchet job on the Kennedy family. The best the press can do in trying to measure such disputes is point to a previous docudrama, The Reagans, to suggest a historical corollary. The Reagans suggested that Ronnie was “insensitive to AIDS victims, and that Nancy Reagan was shown as being reliant on a personal astrologer” (which history also suggests was true in both accounts). Surnow can, of course, assert that the Kennedys were womanizers (which is also historically accurate, however that is defined), and offer a fictionalized account that can display that in all its soap-operatic glory.

What we are left with, though, is competing truth claims—a He Said, She Said of political history and, ultimately, historical truth. But what conservatives realize is that at this moment in time, truth is up for grabs, and popular culture is as good a realm as any (if not better than most) for making historically revisionist claims to alter history toward their preferred readings. With a distrust of elites, a delegitimized news media, a populist-paranoic rise in anti-intellectualism, and a hyper-ideological political culture, what constitutes historical truth (and even contemporary reality) is and will be hotly contested in the foreseeable future. It is a contestation that will be played out repeatedly and with much gusto across media platforms, formats, and genres. When such conflict is derived from a profound difference in our (no longer) shared ways of knowing, I am unsure how society arrives at the “common good.” In sum, if the conflict really is epistemological, I am worried it is going to get worse before it gets better–and frankly, that scares the piss out of me.

It’s convenient for me that you should publish this just before my Media and Cultural Theory class gets to postmodernism next week, Jeff, since it’s a trenchant reminder of the costs of erasing ideas of truth or of the solidity of fact. In the wake of post-structuralism and postmodernism, both of which came largely from the left, many of us convinced ourselves that a key difference between right and left was that the right insisted on a singular truth, one right answer, etc. Yet the rise of the Bush/Cheney “truth is what I say it is” complex has perhaps reminded us of how deeply invested the left is (and needs to be) at least in now insisting that truth is not completely malleable. While Jason kicked off a discussion of the ills of “post-” and other prefixes a week ago here at Antenna, perhaps Bush and Cheney, Rush and Sarah have dragged us into an era of “neo-postmodernism,” in which those of us who once argued “there is no such thing as truth” are now realizing the Pandora’s Box that was opened when conservative politicians picked up the idea and ran with it?

As my use of the word “us” above should suggest, there seems a pedagogic issue here too, and it’s one I wrestle with: can we continue to deconstruct truth in our classrooms if this is the endpoint?

Good point. The “there is no such thing as truth” reading always seemed far-fetched to me, while “truth is contingent” made more sense. The irony comes, though, in that we all emphasized power as the key ingredient in that contingency. Certainly Cheney/Bush and their lapdog branches of government had that sort of power. Where does that power reside now (the hegemony that is old systems of capital, patriarchy, elites intellectually exploiting stupid people, structured inequality, racist thinking, etc.)? Probably so, but shows how powerful such things can be outside of the “who holds power through electoral processes.”

I think the moment that this lightbulb went off for me was when Ron Suskind quoted the White House source as saying “we create our own reality,” while mocking the “reality-based community” associated with liberalism. Even then, Kerry and Democrats were painted as intellectual elites rather than people who could act upon the world. I think Jeffrey is right to distinguish between the idea that “truth is relative” and the idea that “truth is contingent.” But I’m not sure how to make the move to resolve the polarization of the “truth” about history.

I use the Suskind article as one of two contemporary examples to explore Baudrilliard and postmodernism in my cultural theory class. The other is Wall Street and the way that market value is constituted by discourse rather than the reverse.

The longer quote from the Suskind source (rumored to be Turd Blossum Rove himself) is instructive: ”We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

While it might seem that the quote draws inspiration from postmodernism (an empire of signs, perhaps?), I think it’s more straight-up imperialism & propaganda – keep repeating the same lines over again and eventual you (and everyone else) will believe them.

I never read Howard Kurtz’s 2001 book “The Fortune Tellers,” but I remember it being about CNBC, the financial news channels and their role in the bubble of the late-1990s. Interesting picture in the NYTimes two days ago–the Royal Bank of Scotland’s new gigantic American trading floor: notice the TV screens on the columns. Ahhhh–grand delusion.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/18/business/18rbs.html?scp=1&sq=royal%20bank%20of%20scotland&st=cse

Jason, that’s probably a better reading of the quotation (and I’ve heard that Rove was the source, as well).

[…] to be made by conservative activist Joel Surnow (best known for his work on the TV show 24), but Jeffrey Jones has an interesting read of the debate over the documentary and how it comments on the contemporary […]

[…] In other cases, it can lead to the cynical manipulation of historical memory that Jeffrey Jones has recently discussed in a must-read column for Antenna. Or, as Jim Emerson observes, “Without reality-based […]