Men Who Write About Men Who Hate Women

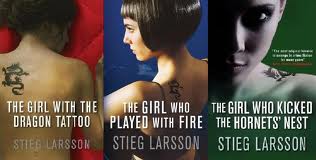

Whether the term “feminist” is being used humorously in an SNL monologue, idealistically by the heroine of a teen comedy series, or strategically by a former half-term governor seeking to mobilize supporters, mainstream discussions of gender and empowerment always catch my attention. Feminism has made headlines this summer as part of the story surrounding Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy, which has functioned as a gift that keeps on giving to the publishing industry. Powell’s is reportedly selling 1500 copies of the books each week (with clerks referring to them as “The Girl Who’s Paying Our Salaries for the Next Few Months”) and the trilogy has significantly driven e-book sales. The Swedish film adaptations of the first two books have performed well in art-house theaters in the United States, and David Fincher’s version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is scheduled for release in 2011. Debates about feminism in the trilogy emerged much earlier in blogs, but have recently circulated more widely in the popular press, fueled in part by a compulsion to find a story in the continuing success of the series.

Whether the term “feminist” is being used humorously in an SNL monologue, idealistically by the heroine of a teen comedy series, or strategically by a former half-term governor seeking to mobilize supporters, mainstream discussions of gender and empowerment always catch my attention. Feminism has made headlines this summer as part of the story surrounding Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy, which has functioned as a gift that keeps on giving to the publishing industry. Powell’s is reportedly selling 1500 copies of the books each week (with clerks referring to them as “The Girl Who’s Paying Our Salaries for the Next Few Months”) and the trilogy has significantly driven e-book sales. The Swedish film adaptations of the first two books have performed well in art-house theaters in the United States, and David Fincher’s version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is scheduled for release in 2011. Debates about feminism in the trilogy emerged much earlier in blogs, but have recently circulated more widely in the popular press, fueled in part by a compulsion to find a story in the continuing success of the series.

Larsson, who died in 2004, was a progressive feminist journalist who created a detailed storyworld in which crimes of sex trafficking, rape, and domestic abuse are acknowledged and exposed, and men who perpetrate violence  against women are made to suffer. Reviewers consistently interpret Lisbeth Salander, a chain-smoking, kick-boxing, bisexual hacker who is one of the trilogy’s two main characters, as feminist, while ignoring the other lead, journalist Mikael Blomqvist, presumably because he is male (part of a long tradition of equating feminism with women). The trilogy’s first book was published in Sweden under the title Men Who Hate Women, which Larsson insisted upon, apparently because it was significant to his vision. The marketable Girl Who … titles originated with the publication of the trilogy in the UK, introducing a meaningful shift from “women” to “girl.” (“Feminism” is apparently not such a loaded word in Sweden, a country where feminists still routinely protest pay inequities and feminist-influenced state policies have reshaped cultural attitudes about work and family.)

against women are made to suffer. Reviewers consistently interpret Lisbeth Salander, a chain-smoking, kick-boxing, bisexual hacker who is one of the trilogy’s two main characters, as feminist, while ignoring the other lead, journalist Mikael Blomqvist, presumably because he is male (part of a long tradition of equating feminism with women). The trilogy’s first book was published in Sweden under the title Men Who Hate Women, which Larsson insisted upon, apparently because it was significant to his vision. The marketable Girl Who … titles originated with the publication of the trilogy in the UK, introducing a meaningful shift from “women” to “girl.” (“Feminism” is apparently not such a loaded word in Sweden, a country where feminists still routinely protest pay inequities and feminist-influenced state policies have reshaped cultural attitudes about work and family.)

The major questions raised about feminism in the franchise are basically summarized by Missy Schwartz in an article for Entertainment Weekly that owes an unacknowledged debt to multiple bloggers. She claims that Larsson both repudiates and exploits violence against women, and uses as an example a “female character” who is “choked to death with a sanitary napkin down her throat.” Even though I had just read the books and seen the first film when this article was published in June, Google had to help me figure out what Schwartz was referring to: a female victim of a male serial killer who used Old Testament biblical passages as fuel for his misogyny. The victim is not a “character” as such; the details of her murder are discovered by the protagonists in the course of their investigation and the circumstances of her death add to their understanding of the criminal they seek. The serial killer’s crimes, supposedly based in religious zeal (referenced more extensively, but in a way that similarly overemphasizes the role these events play in the overall narrative, here), add one more layer to Larsson’s social critique, which extends to psychiatry, law enforcement, and the justice system.

The complaint that the trilogy cannot be feminist because of the way it depicts violence against women is a common one; it perhaps implies that in order to be “feminist” the storyworld would not acknowledge the realities of gendered brutality, and seems to miss the point that violence against women is presented as a direct result of institutionalized patriarchy. In Dragon Tattoo, Larsson offers statistics related to male violence against women in Sweden at regular intervals; many bloggers who critique the violence in the films openly confess that they have not read the books, which raises the issue of how the story and its characters shift from one medium to the other.

Schwartz also contends that Salander’s breast augmen tation, which the character has undergone in the second book, but not in the second film, is anti-feminist. Although she rarely exhibits any understanding of how she might be viewed by other people (readers and viewers frequently interpret Salander as a high-functioning autistic), this criticism suggests that she purchased “solid, round breasts of medium size” (Girl Who Played with Fire 17) in order to become a sex object, an idea that runs counter to every other aspect of her behavior and personality. The claim that feminism is at odds with plastic surgery is also dated, ignoring the feminist school of thought advocating individual empowerment through the construction of identity.

tation, which the character has undergone in the second book, but not in the second film, is anti-feminist. Although she rarely exhibits any understanding of how she might be viewed by other people (readers and viewers frequently interpret Salander as a high-functioning autistic), this criticism suggests that she purchased “solid, round breasts of medium size” (Girl Who Played with Fire 17) in order to become a sex object, an idea that runs counter to every other aspect of her behavior and personality. The claim that feminism is at odds with plastic surgery is also dated, ignoring the feminist school of thought advocating individual empowerment through the construction of identity.

Issues of translation (from books to films, from Swedish to English and more than thirty other languages) complicate the questions raised about Larsson’s gender politics, but the discussion should draw our attention to the general lack of consensus on “feminism” as a theoretical concept, a practice, and a political ideology. In the United States, the phrase “post-gender” is gaining traction, and “feminism” is often referenced as a dirty word. Lisbeth Salander is not an “every woman” character (she does, after all, use a cell phone to dig her way out after being shot several times and buried alive) and the feminist appeal of Larsson’s storyworld is not solely due to his invincible heroine. His crime fictions resonate because he views social problems through the lens of gender and offers tough, intelligent protagonists (female and male) who fight to change the status quo.