Tweets of Anarchy: Showrunners on Twitter

While there have always been strong personalities behind-the-scenes in television, including recent examples such as David Milch and Aaron Sorkin, until recently there were very few outlets in which the general public could directly bear witness to the character of television showrunners; stories were written about their personalities and how they influenced the creative process of their respective series, but it was predominantly second hand information. Outside of award show acceptance speeches, occasional interviews, DVD commentaries, or (in Sorkin’s case) run-ins with the law, the television showrunner was a largely private figure during the day-to-day airing of their series.

While there have always been strong personalities behind-the-scenes in television, including recent examples such as David Milch and Aaron Sorkin, until recently there were very few outlets in which the general public could directly bear witness to the character of television showrunners; stories were written about their personalities and how they influenced the creative process of their respective series, but it was predominantly second hand information. Outside of award show acceptance speeches, occasional interviews, DVD commentaries, or (in Sorkin’s case) run-ins with the law, the television showrunner was a largely private figure during the day-to-day airing of their series.

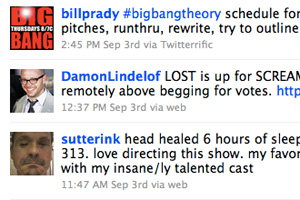

However, showrunners are now becoming active participants in conversations surrounding their shows, both formally (Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse’s Lost podcasts) and informally (Louis C.K.’s decision to wade into comment threads of Louie reviews); combined with their more prominent role in DVD bonus features and the proliferation of television journalism online, showrunners are becoming veritable celebrities among viewers of television. This is perhaps no more apparent than on Twitter, where showrunners (including Lindelof, Cuse, ,C.K., and numerous others) gain tens of thousands of followers who desire to know more about who is behind their favourite series.

In many ways, Twitter is a fantastic opportunity for showrunners. The Big Bang Theory’s Bill Prady has been using his Twitter feed to remind viewers that the show is moving to Thursday night, while Community’s Dan Harmon has been using his Twitter feed to help bolster the show’s viewers against the insurrection of Prady’s series to their timeslot (the two even collaborated on matching avatars, each featuring “THU 8/7c,” to build hype for their impending battle). With this sort of behaviour, often done in conjunction with answering fan questions or offering insights into the production of the series, showrunners directly facilitate fan community.

However, as most showrunners have discovered, Twitter can be a double-edged sword. While Bones’ Hart Hanson is an active participant on Twitter in promoting his series, he also bears the brunt of the attack when fans become frustrated with the series (in particular the drawn out romantic tension between its leads). And while Lindelof and Cuse were showered with praise when Lost hit its high notes, they were inundated with frustration following the divisive series finale.

By putting their reputations on the line – and online – showrunners open the door to potential rewards (viewer loyalty, new viewers, professional transparency), but as they also face definite risk. There is perhaps no better example of this risk/reward principle than Sons of Anarchy’s Kurt Sutter, who one would likely classify as television’s renegade showrunner. Giving voice to every showrunner’s id, Sutter uses Twitter and his personal blog to criticize the television industry and his critics through a mix of cogent analysis and four-letter words; where other showrunners avoid calling out the Emmy Awards when their show is ignored, or resist responding to critics who write negative reviews, Sutter has made a conscious decision to present his own perspective without any sort of filter.

The question, at this point, is whether or not his “larger than life” personality has become larger than the show itself. While his notoriety has been a source of promotion for the series, which has only grown in popularity since he began blogging and tweeting in earnest, there is a risk that his actions could overpower the series’ narrative; the Los Angeles Times, for example, chose to profile Sutter rather than his series ahead of its third season premiere.

Some would argue this is actually valuable: the brash masculinity of Sutter’s online persona is heavily echoed within the series itself, meaning that the association could be seen as an effective (and novel) way to market the series. However, if Sutter’s extra-curricular activity becomes a primary association for potential viewers – which is happening more as his Twitter feed and blog posts are extending beyond social media to a more general audience (as the L.A. Times profile and mainstream coverage of his criticism suggest) – it is possible that the series’ subtleties, which include strong female characters, could be obfuscated. What fans could read as refreshing honesty could be read as outright arrogance by others, and while Sutter would likely argue that those put off would be unlikely to watch the show in the first place there remains the potential for lines to blur between the series and its creator.

For the most part, of course, these kinds of issues will largely remain confined within a small subsection of the viewing public – Sutter has 12,000 followers on Twitter, compared to Sons of Anarchy’s 4.1 Million viewers. However, the active participation made possible by Twitter and other forms of social media has changed the dynamics of audience/showrunner relationships, and as showrunners like Sutter test the boundaries of this new dialogue we learn more about where this relationship may be headed in the future.

Editors’ Note: a reminder that we like to keep comments civil and constructive here at Antenna. Those comments that seek to insult or vent, or that don’t materially contribute to the discussion, will be withheld.

Great post; in some ways, this is nothing new (J. Michael Straczynski was extraordinarily active on USENET during Babylon 5’s writing and production and airing, back in the mid-1990s). What seems to be new to me are the ways that it’s gone mainstream (ten years ago, would people like Sutter have ever considered interacting with fans online? Maybe, but it’s a more socially accepted soapbox nowadays) as well as how it now seems to be a coordinated tactic for some shows (the BBC’s Sherlock aired in late July this past year; shockingly, all three producers happened to get Twitter accounts in the week or two before it transmitted).

One thing to note — it’s a small subsection (Sutter’s 12,000) that follow some of the figures on Twitter. But, being a more public venue than USENET ever was, all it takes is one crazy statement to drive many, many more readers to the tweet. That 12,000 only reflects the people who are already on Twitter, not the people who follow a link to an individual tweet.

Sean, you nicely point out the crux of this situation: it’s not that showrunners are just now becoming interested in interacting with fans, but rather that the outlet exists where it is both more socially acceptable and more widely accessible.

I’m also especially interested in how these tweets are disseminated (as my link to TV Guide indicates). Outside of the context of Twitter, most tweets lack, well, context, and so it will be interesting to see how this coverage evolves as more showrunners turn to Twitter.

Great post. I’ve been amazed at how my perception of a person from Twitter affects how I think of their creative product.

If I hear one more time that Sutter has “refreshing honesty” my head’s going to explode. It’s not refreshing or honest to be an asshole for effect. And it’s certainly not refreshing or honest to, for example, complain on twitter about something your actor said to a journalist before speaking with the actor, and then complain that journalists picked up on his complaining. I hadn’t watched the show before following him, and would never watch it now (and have since unfollowed.)

I’ve also had to unfollow showrunners of shows I love, like Dan Harmon, when their twitter personas started to grate – it made me worry it would affect my enjoyment of the show. On the other hand, I follow writers of shows I don’t watch much of because they’re entertaining, funny, and insightful, and it does make me root for their shows even if I’m not an avid watcher.

Following Dan Harmon has only made me love Community more (my obsession with the show’s deconstruction of the traditional sitcom had already bordered on the insane). Every day I want to both hug and slap him- I assume that’s what he’s going for. And he made me think even more about pooping than I already did, something I would have hardly thought possible.

Following Hart Hanson has only weirded me out, because who knew there were people so obsessed with Bones? And all those people at this moment are saying, “Who knew there were people so obsessed with Community?”

I’m on the same page, Kelly – Harmon personifies Community’s “Id” for me, and his online presence gives me insight into the show’s sense of subversion.

Also, Harmon’s scatological and confrontational Twitter presence is coupled with interviews (like this one with Alan Sepinwall) which keep any single comment or persona from becoming “definitive.” The same goes, personally speaking, for Kurt Sutter, so it is something that we all approach on an individual level (which is why I resist making the argument in the piece that this is definitively influencing viewers).

However, as Diane’s comment shows, that potential is certainly there.

This is a great article. And I think it’s great to have a comment section under it, and I am getting even more important information from the comments than I am from the article itself. Diane, above, for instance, contributes information about her point of view that I find edifying and refreshingly positive.

This is what I mean, actually. I’m a viewer who said I love your show, but as usual you felt the need to respond sarcastically to the negative than the positive. Do you care MORE that I didn’t find your tweets entertaining than that I think your show’s entertaining? You’re talented and make one of the best shows on TV. So you have one less Twitter follower. I unfollowed so you wouldn’t have one less viewer. This is kind of the point of the article – your comments here and on Twitter affect how I view the show, and I don’t want that to happen.

Actually, if you think about it, your response to my response to your comment goes to support the point I’m making in my response to your comment more than your comment supports the point of the article, and at least half as much as your tweets about your response to my response to your comment on the article about my tweets support the point of the show itself. At least that’s MY opinion.

Now *this* was funny.

Nice post, raising an issue we can definitely talk more about at Flow about critic/fan/creator interplay.

Dan’s comment raises a related issue – what happens on a blog when showrunners show up? The Louis CK examples have been in reaction to positive commentary (and I’ve found his comments really engaging and edifying), but sometimes creators show up to rebut a critic. When this happened to me, with Tim Kring on a post I wrote excoriating Heroes, I felt obliged to hedge my criticism and backpedal a bit. In part, this is because I didn’t want to alienate a potential industry source for my research, but also as a writer, I know how much it can hurt when people harshly criticize my work. Now I always write criticism with the awareness that creators might stumble-upon or even comment on what I have to say. Is this a good thing?

And for the record, I love Community and think Dan’s Twitter feed is streets ahead of other showrunners.

I think that you raise a number of interesting points here, Jason.

Louis C.K.’s comments interest me because they’re not so much responding to the review as they are adding to it: he seemed to be interested in expanding discussion, and further explaining the series’ function and purpose, and decided to interact with the community surrounding the posts rather than emailing the critics (which he certainly could have done, and then waited for the interview to post or the like). It’s not dissimilar from showrunners who would wade into the TWoP forums back in the day, albeit now merged more clearly with secondary textual analysis (which is what makes it really fascinating to me).

I’m equally fascinated, though, by the notion of self-censoring (however subtly) in order to take the “Stumble-upon” factor into account. I recently discovered that a showrunner was reading my largely positive reviews of their series, and my mind immediately went to the one negative review I had written. I don’t regret anything I wrote, but I do think that such knowledge would influence future writing, whether I want it to or not. It’s also something that would be different for those in different positions, raising questions about whose job it is to write negative criticism and what sort of different levels of cultural capital bloggers, fans, critics, scholars and other groups have in such matters.

But, rather than going on, let’s save it for Flow.

I think it was Sepinwall (maybe Poniewozik) who said his only reaction to knowing showrunners/actors/etc are reading his posts is to not be gratuitously mean, but then he wants that to be a goal anyway. I think that’s the best approach, no self-censorship, but hard in practice. I don’t think it changed my House reviews, for example, but I did stop doing Canadian TV reviews. The difference in professionalism between the respective reactions was key though.

And of course it occurred to me that Sutter or Harmon might read my comment here but figured this is audience/critic turf, and it’d be pretty hypocritical of those guys in particular to object to someone expressing an opinion.

It was Sepinwall.

And it was probably just Harmon’s assistant that commented. I mean, how could a showrunner have time to visit blogs and websites…COMMUNITY is filming right now!

I would generally agree with Sepinwall. Learning how many showrunners read my stuff has made me use snark a lot less, which tends to be a goal I have anyway. I try not to go easy on shows – even shows I really like – when they have off episodes, but if I have a criticism, I try to express it as clearly and respectfully as possible. I doubt a showrunner will read it and agree with me so much that he or she changes direction for the show, but I like to imagine he or she can say, “I disagree, but I see where you’re coming from.” That’s the goal, at least.

A bigger problem is this simple fact: Over the course of a show, journalists who cover it are usually also critics who review it, and they’ll meet the show’s principals and creative crew many, many times. It’s not the same thing as an author or director you might interview once or twice (though certainly someone like Roger Ebert has met directors he admires many, many times). The longer Community is on, the more times I’ll talk to its cast and producers, and the less they’ll be abstract people on my TV and the more they’ll be, y’know, human beings I’ve met and talked with several times, even though it’s in a completely professional capacity. I’m not saying this problem is unique to TV coverage – all branches of journalism have a similar question of just where the line is – but it’s certainly one I’ve been contemplating, the more interviews I do.

Todd – important point that this is a problem with all journalism, and thankfully the stakes of getting enamored with insider sources are far lower for TV critics than political or military journalists.

Another facet of this problem which hasn’t seemed to impact the TV crit-osphere (yet?) is the Peter Travers Effect – writing reviews not to offer insight, but to generate pull quotes for press packs & posters. Once Myles and Todd start getting quoted on DVD covers, we can pillory them for selling out…

This is a great article. While I don’t really follow showrunners on twitter, I’ve noticed a very similar phenomenon with comic book creators, who have formed an active and vibrant community in the twittersphere. Comics creators have always been more accessible than a lot of creative types, because of the smaller audience and the number of conventions, signings, and other appearances they rack up, but twitter has really broadened their exposure. It’s hard to be a comic book fan and NOT get to know the creators more personally through twitter (and the seemingly weekly website and podcast interviews they give), and that has, I think, definitely affected the audience relationship.

I wonder, additionally, how the relationships between the creators affects audience reception — within comics, at least, the creators very frequently hold conversations among themselves, and evidence of their friendships beyond the professional boundaries is abundant. Does recognizing constellations of like-minded creators who are likely to communicate and collaborate influence the perception of those people, for the audience? Are people more likely to read Matt Fraction’s work because of his friendships with Warren Ellis and Brian Michael Bendis?

I also agree with those who feel the tension, as critics, between being honest and being nice to creators you’ve gotten to know. I’ve been relatively lucky in that the creators I’ve formed relationships with put out quality work that I don’t have to criticize frequently, but I know there are opinions, even very mild and polite opinions, that I’ve stopped myself from expressing on twitter because I worried it might upset someone I admire.

[…] When he spoke about his interaction with fans (and non-fans) on Twitter, he noted that this was not something he discussed with the network, nor something he thought would “become a thing.” He talked about how it gave him that sense of hope, that there were perhaps people out there who didn’t watch but might watch again, who could help the show pull off a stunning upset and start trending upwards. Ultimately it wasn’t enough the save the series, but I think it created a profile for him as a writer which will serve him quite well in the future, and offered an interesting case study for future showrunners who choose to engage with fans from the beginning (or perhaps even before the beginning) in this fashion (which, if you missed it a few weeks ago, I wrote about a bit for Antenna). […]