Sifting Through the Trash: Guided Spectatorship at the Maury Show

I’m a sucker for “Trash TV.” I love watching out of control teens berate their parents on Jerry Springer. Seeing Steve Wilkos yell at the guests on his own new show fills me with even greater joy. Heck, even the commercials for getting out of debt and going back to school—strategically placed in the mid-morning television hours for potential slackers—gives me a rise. But more than any show of the “trash” genre, I love Maury—a show hosted by TV personality Maury Povich that has been running on the air (in one iteration or another) for nearly twenty years.

I’m a sucker for “Trash TV.” I love watching out of control teens berate their parents on Jerry Springer. Seeing Steve Wilkos yell at the guests on his own new show fills me with even greater joy. Heck, even the commercials for getting out of debt and going back to school—strategically placed in the mid-morning television hours for potential slackers—gives me a rise. But more than any show of the “trash” genre, I love Maury—a show hosted by TV personality Maury Povich that has been running on the air (in one iteration or another) for nearly twenty years.

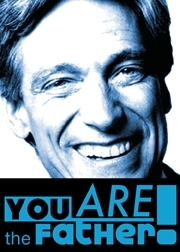

For as long as I’ve been watching Maury, I could never pinpoint what was so appealing about revealing the identity of a promiscuous woman’s “baby daddy,” or the truth as to whether or not some creepy-looking truck driver was lying about an affair with a male co-worker. Something about the show’s dynamics brought me back to the couch time and time again. So one day, like any intellectually curious researcher with too much time on his hands, I went looking for answers directly from the source.

On March 5th, 2010, the missus and I drove up to Stamford, Connecticut, in order to participate as audience members of the Maury show. Our episode, “Sexy Secret Fantasies Revealed and Fulfilled,” first aired on March 25th, 2010, and featured copious “hot bods” and lame stories from scantily-clad guests. In retrospect, the most memorable part of being an audience member was learning how the show achieves such a consistently united, cacophonous reaction from its audience: through coaching from the production crew.

Before filming began, Maury’s energetic producer got the crowd roaring with a brief lecture on how to get on TV: “If [a guest makes] a corny joke, laugh TEN TIMES HARDER than usual,” he boomed. “Exaggerate your reactions; make them bigger than real life—ham it up, people!” After explaining how to “properly respond” to typical situations encountered on the show, he got the audience to practice cheering vivaciously by promising free T-Shirts to the most vocal participants. When someone didn’t participate enthusiastically enough, he would playfully single them out; fellow audience members were instructed to boo such deviants, and they kindly obliged. It was clear to me that the Maury crew was tacitly facilitating and crafting a very specific behavioral response from the audience—seemingly outside of the participants’ own realm of awareness.

The producer, adopting the role of the authority within the audience’s hierarchy, establishes a play frame with the audience in which they become pre-conditioned to adhere to the show’s directions and prerogatives. Appeals are made to the audience through intrinsic rewards, and nonconformity is punished via directed crowd jeering—this is tolerated because of the play frame that serves to suspend the full force of reality. By allowing the show’s producer to guide their actions, the audience members partake in an interactive scene that may actually contest or override their own constructed boundaries of political correctness with regards to race, the social organization of class, conception and fidelity, or ethnic and cultural stereotypes. At the producer and editors’ instruction, the audience’s outward expression of emotion is meant to be received as the “right” viewpoint, while the guests are either sympathetic figures or antagonists, depending on the contextual storyline.

In essence, the audience underscores and champions the desired editorial angle of the show’s episode. The viewers at home are meant to psychologically connect with this ethos by rhetorically strategizing an imagined position of moral or cultural superiority over the episode’s villains. Thus, the Maury show’s real power comes from rhetorically granting permission for fans to explore contentious or taboo subject matters in an open forum. On the set of Maury (or at home watching along), it is acceptable to poke fun at “white trash rednecks” or mock black men that fathered numerous children with six different women—on this show, guests’ actions can be critiqued by tapping into the unspoken prejudices of its audience members. The viewers’ internal anxiety over political correctness becomes neutralized as the audience subjugates the guests’ behaviors or actions while reinforcing their superior position.

With these observations and analyses in mind, should I be ashamed to admit that I enjoy watching the Maury show? Should you? I don’t think so.

I am a folklorist, and one that is particularly interested in how people express themselves through subversive material in an effort to circumvent societal restrictions on decorum. As much as I would like to say otherwise, I subscribe to the adage that everyone has their own prejudices within them and that these perspectives have been shaped and acquired throughout their lives. The “Trash TV” genre allows its viewers—some of whom may be underprivileged given the aforementioned commercials’ targeted demographic—to come away with a greater sense of normalcy and superiority through the misfortunes and buffoonery of guests whose personas fall below their threshold of respectability. While feeling “better than” someone else isn’t typically a socially-sanctioned practice, it is clear that the Maury show’s antagonists are portrayed as lowlifes that deserve to be seen as beneath us. Viewers are led to walk away from an episode entertained, but also with a greater sense that their own lives are not as bad as “those people” on the screen; the feeling is subconsciously reinforced every time that the show is watched. As that point of internal satisfaction is reached, the mission of the show’s producer is fully accomplished.

How’s that for a final thought?

Trevor, your fascinating piece made me think of another example, not far from “Trash TV”: WWF/WWE’s Monday Night RAW in its original format on USA. When the show initially went on the air in early 1993, it was broadcast live from the ramshackle Manhattan Center in NYC. The place was a “toilet bowl,” as the announcer Gene Okerlund once called it, and the aim of the show was to give wrestling a “live” feel. The crowd was small, the venue intimate, the announce crew included the comedian Rob Bartlett, and the fans were treated to scantily clad “Raw girls” who sauntered around the ring before matches holding signs that read, “We like it Raw,” and such.

Spectatorial guiding seemed much less complex– wrestling almost always goes for the simplest emotions and for the biggest and easiest “pop”– although no real research has been done.

Still, in the long shots that tended to lead into the broadcast, one could see, tucked into the corner of the frame now and then, a stage manager of sorts twirling a towel around, and pumping his hands to get the crowd “revved up” as the broadcast began. The raucous nature of the crowd– and the often creative, even off-color, chants it would slip into– made this one of the wildest atmospheres ever for a mainstream wrestling show. Here, too, I suspect, the audience was encouraged to “neutralize” its inhibitions, and to indulge in the spectacle.

I doubt that the producers were looking to propose a moral stance to the audience, however. Nonetheless, the conditions, apparently cued by the producers, encouraged overblown responses to misogynist, gutter-level attractions between and sometimes even during the matches.

This was a far cry from the “quality” broadcast (relatively speaking) that was WWF’s SATURDAY NIGHT’S MAIN EVENT on NBC.

Perhaps slightly off-subject as an example, but I thought I’d share it.

Hi, Colin! Thanks for sharing your insights and experience! I definitely see the correlations that you mention, and as a fan of “old-school” wrestling myself, I agree that the suspension of inhibitions has likely been a major part of the fun for spectators. Have you checked out the book “Wrestling to Rasslin’: Ancient Sport to American Spectacle” by Morton and O’Brien, or “Professional Wrestling: Sport and Spectacle” by Sharon Mazer? You might enjoy those academic treatments on the rhetoric of performance through the lens of pro wrestling.