You Can Patent That?

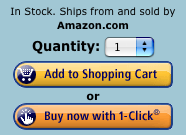

In a mad rush of last minute shopping for my Mom’s birthday, I recently bought her Tina Fey’s book Bossypants from Amazon. (I think it was the spoof-review from Trees – “Totally worth it.” – that sealed the sale). Since Amazon has my credit card and address info on file, I ordered the gift in one click. Considering everything we can do with technology today, this particular feat hardly seems worthy of discussion in a forum as esteemed as Antenna. But if you’ve ever clicked once to buy, you’ve taken part in an activity that has implications across the North American technology sectors for how consumers interact with the books, music, and movies they love on their digital devices.

In a mad rush of last minute shopping for my Mom’s birthday, I recently bought her Tina Fey’s book Bossypants from Amazon. (I think it was the spoof-review from Trees – “Totally worth it.” – that sealed the sale). Since Amazon has my credit card and address info on file, I ordered the gift in one click. Considering everything we can do with technology today, this particular feat hardly seems worthy of discussion in a forum as esteemed as Antenna. But if you’ve ever clicked once to buy, you’ve taken part in an activity that has implications across the North American technology sectors for how consumers interact with the books, music, and movies they love on their digital devices.

In the U.S., Amazon has had a patent on this one-click purchasing system since the late 90s. It’s called “Method And System For Placing A Purchase Order Via A Communications Network”. It’s a special class of patent known as a “business method patent”, since it covers a particular way of doing business. Most patents cover specific gadgets, like a new broom or a better mousetrap. Patent-holders get a 20-year right to prevent others from making a similar invention and profiting from it. Business method patents grant ownership over technologies and the ways those technologies are put to use.

Relatively rare before the 1990s, the U.S. patent office started handing out business method patents more regularly with the rise of computers and online retail services. There are now patents on methods of running online auctions, the use of electronic shopping carts and even the selling of audio and video downloads over the Internet. Since the mid-90s, applications for business method patents in the U.S. have skyrocketed from hundreds to tens of thousands per year.

Here where I am in Canada, we haven’t experienced the same surge, mostly because the wording of our Patent Act seemingly excludes business methods. But that may be changing. Amazon’s quest to patent the one-click system here is currently at the Federal Court of Appeal, after 13 years of rejections, appeals, and reversals.

Business method patents are troubling because they grant a monopoly not just over a particular technology but ultimately over ways of doing – over ways of interacting with technology. They allow patent holders to stake a claim in what is, in essence, human behaviour. (Apple, for example, has patents covering certain gestures for interacting with their touch-sensitive gizmos).

The absurdity of business method patents is highlighted by Amazon’s use of their 1-click patent in the U.S. In 1998, the company used their 1-click patent to sue rival Barnes & Noble, alleging the “Express Lane” feature on B&N’s website was infringement. B&N had to alter their site so that purchases involved two clicks instead of one. Amazon essentially argued that its patent on a specific use of web browser “cookie” technology also gave it control over an entire method of buying digital stuff.

Business method patents create a blanket of legal hurdles and licensing fees that smother inventors’ ability to innovate. For example, a recent study by James Bessen and Michael Meurer suggests there are upwards of 4,319 patents an entrepreneur could be violating just by selling merchandise online. This patent “thicket” makes developing new gadgets and software more expensive – costs that consumers experience in the form of higher prices.

As more e-commerce moves to mobile phones and other portable devices, these platforms will face a similar land run. In fact, a recent investigative report on This American Life and NPR (“When Patents Attack!) showed how business method and software patents are increasingly causing headaches for big and small tech companies alike. Companies without actual products (non-practicing entities in biz-speak) are amassing huge portfolios of patents and using them to attack actual developers and hardware makers, trying to force them to pay stifling licensing fees.

Companies like Lodsys (one of the shell companies This American Life affiliates with Intellectual Ventures). Earlier this summer, the company sent out infringement notices to half a dozen developers who make applications for Apple’s iPods and iPhones. These are small developers – makers of calculator apps and twitter clients – who allow users to buy upgrades to their programs from within the applications themselves. Lodsys, a company that doesn’t make any competing apps, claims it has a patent on in-app purchasing. They are demanding a licensing fee of 0.575% for all U.S. sales of the apps until their patent expires. While Google, RIM, or Apple have the legal and financial resources to deal with such demands, smaller developers often don’t.

So next time you click once to buy, ask yourself whether the process is so unique and novel that Amazon should have a 20-year monopoly to it. The basic properties of the Internet (e.g. many-to-many communication, hyperlinks, etc.) opened up new ways for users and companies to interact. These qualities are just as responsible for new ways of doing business as any specific business method. If patents are supposed to spur innovation by sharing discoveries while also protecting inventors’ ability to profit from their ideas, we need to ask whether they are meeting this goal, or whether they simply act as quiet quests for control over information and cultural practices.