The Deanna Durbin Cult

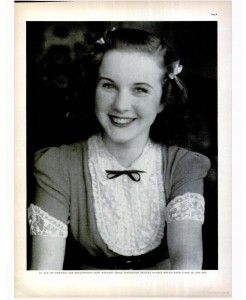

On April 30th, the Deanna Durbin Society released a news report informing the world that retired actress, former child star, and classical Hollywood darling Deanna Durbin had died, age 91, in a small village in France, where she had been living with her family since 1949. Fans and prominent film buff mavens, such as Tim Lucas, quickly distributed the news on social media, and, with a day delay or so, mainstream media outlets followed (especially those in Canada – Durbin was from Winnipeg). As the Internet Movie Database and multiple obituaries point out, Durbin was best known as a star of operetta films in the 1940s. She was first signed by MGM in 1936, and appeared with Judy Garland in the adorable short Every Sunday (Felix Feist, 1936). In the film, Durbin and Garland sing a duet, a sort of duel between two takes on the same tune: Garland’s jazzy style versus Durbin’s more classically schooled interpretation.

On April 30th, the Deanna Durbin Society released a news report informing the world that retired actress, former child star, and classical Hollywood darling Deanna Durbin had died, age 91, in a small village in France, where she had been living with her family since 1949. Fans and prominent film buff mavens, such as Tim Lucas, quickly distributed the news on social media, and, with a day delay or so, mainstream media outlets followed (especially those in Canada – Durbin was from Winnipeg). As the Internet Movie Database and multiple obituaries point out, Durbin was best known as a star of operetta films in the 1940s. She was first signed by MGM in 1936, and appeared with Judy Garland in the adorable short Every Sunday (Felix Feist, 1936). In the film, Durbin and Garland sing a duet, a sort of duel between two takes on the same tune: Garland’s jazzy style versus Durbin’s more classically schooled interpretation.

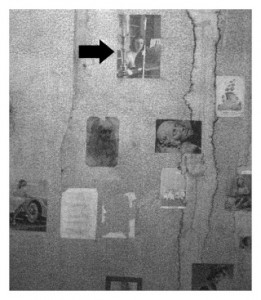

The distinction is one that would permeate Durbin’s screen image: always the ‘ideal daughter’, never any rawness of nerve, unresolved hurt, or riskiness. It certainly worked. By the early 1940s Durbin was one of the industry’s most popular and best-paid actresses, second only to Bette Davis. She made 21 feature films between 1936 and 1948. The public loved her operetta films, musical romances full of sweetness and smiles, such as the highly successful Three Smart Girls (directed by her mentor, Henry Koster, 1936) and Mad About Music (Norman Taurog, 1938). Rarely did she step outside that mold (she did once with the noirish Lady on a Train, directed by her future third husband, Charles David, once a production manager for Jean Renoir). Durbin’s success made her a worldwide celebrity. She was the favourite actress of Anne Frank (who had a picture of Deanna on her wall), and Winston Churchill’s, and Benito Mussolini’s. Then, at the age of 27, and much to everyone’s astonishment, Durbin quit the business, and retired into reclusive anonymity. Why? She said she never enjoyed movies and fame, and just wanted to be “nobody”.

Aside from the nostalgia it triggers for a kind of film industry that is long gone, that maybe never was as imagined, and that most people alive today only know from the most unreliable of sources – the movies and their publicity machines – the figure of Durbin is fascinating today because of how it embodies a sensibility within stardom: that of the cult of the child star. A few years ago, I discovered a book in my department’s office kitchen, abandoned in a delicately placed cardboard box, tucked away amidst ditched textbooks (like a baby orphan on a church’s steps). The book was called Hollywood’s Children: An Inside Account of the Child Star Era. It is a bitter confessional, yet also surprisingly socio-historical, memoir written by Diane Serra Cary, a child star in the 1920s, known as Baby Peggy, one of several children catapulted into stardom in the golden period of classical Hollywood cinema. Hollywood’s Children offers a rare insight into the industry of child stars, and Baby Peggy’s intimate knowledge of the trade gave her a front-row seat to the lives of Mickey Rooney, Jackie Coogan, Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, and Deanna Durbin.

At the time when I found Hollywood’s Children I was researching Hollywood star fandom for a book on cult cinema. I was struck by the intensity and ambivalence of child star cults. Child and teen actors have always been a point of fascination for film audiences. They are universally adored, yet at the same time there is a sense they are out of place, their physical and mental wellbeing endangered by the machinery of Hollywood. Conflicts between perceptions of child labor (exploitative, slave-labor, exhausting) and perceptions associated with children (pure, naïve, innocent, playful, cute, asexual, impulsive) put child acting outside of normality and open debates that pitch a poor defenseless youth against an evil, faceless corporation. Such debates have saturated the reputations of Garland, Natalie Wood, Margaret O’Brien, and many other child actors – including Deanna Durbin – and they have fuelled cult reputations in which admiration for acting is precariously negotiated against concerns about labor conditions. Put in that context, Durbin’s yearning to be “nobody” acquires added meaning: she already felt she was “no-body” in Hollywood, so in a sense she abandoned being nobody.

Cult followings of (former) child and teen actors are often deeply involved in identity-affirmation. Such involvements are combined with anxieties over the cultural appropriation of visual representations of child actors. In her study of the gay cult of Garland, Janet Staiger details the similarities between public perceptions of Garland’s adult “nervous exhaustion”, “intensity,” “insecurity,” and “elf-like androgyny,” and contemporaneous views of gays in American culture. She proposes that this similarity might be one of the reasons for the prominent queer cult appeal of Garland, articulated through organizations for gay liberation such as the Radical Faeries. Only few followings are as outspoken as Garland’s, and Durbin’s fans have been, overall, located too much in the middle of the mainstream to qualify as a ‘pure cult.’ That said, within the mass cult existed a hardcore cult. Around Durbin arose an incredibly well-organized and collectible-heavy cult following, administrated by the Deanna Durbin Society. Some of the fandom for Durbin distinguished itself through its appetite for dolls (we’d call them figurines today) of cute, doll-like Deanna – a twist not out of place in a satiric comedy.

Cult followings of (former) child and teen actors are often deeply involved in identity-affirmation. Such involvements are combined with anxieties over the cultural appropriation of visual representations of child actors. In her study of the gay cult of Garland, Janet Staiger details the similarities between public perceptions of Garland’s adult “nervous exhaustion”, “intensity,” “insecurity,” and “elf-like androgyny,” and contemporaneous views of gays in American culture. She proposes that this similarity might be one of the reasons for the prominent queer cult appeal of Garland, articulated through organizations for gay liberation such as the Radical Faeries. Only few followings are as outspoken as Garland’s, and Durbin’s fans have been, overall, located too much in the middle of the mainstream to qualify as a ‘pure cult.’ That said, within the mass cult existed a hardcore cult. Around Durbin arose an incredibly well-organized and collectible-heavy cult following, administrated by the Deanna Durbin Society. Some of the fandom for Durbin distinguished itself through its appetite for dolls (we’d call them figurines today) of cute, doll-like Deanna – a twist not out of place in a satiric comedy.

More even than the fandom for Shirley Temple, which remained ‘modest,’ or for Judy Garland, which developed, a little later, into something ‘unwieldy,’ Durbin’s fans were the model of the perfectly disciplined film cult: immersive, cohesive, self-sustained, introspective, and above all loyal (it is instructive to see parallels with television fandom today, as it is described by Katherine Larsen and Lynn Zubernis in Fandom at the Crossroads. After Deanna herself dropped out, the fandom remained, it even fortified (as cults tend to do in the absence of new materials). To this day it is active as ever – it is in my eyes no coincidence that news of Durbin’s passing arrived through fandom channels first. (For a glimpse into Durbin’s fan following, see Deanna Durbin Devotees – make sure to scroll down to Benito Mussolini’s open letter to the star!)

We can only speculate on what identity-affirming role Durbin’s image on the wall in Het Achterhuis played for Anne Frank. Yet I feel encouraged to see it as slightly more than merely a signal of popular mainstream culture’s pin-ups penetrating the most secretive of girl’s rooms but instead – perhaps –something with somewhat of a personal significance, something that establishes an intimate and unlikely contact between the most public and the most private realms of understanding reality that form the core of a cult following, something predicated on a simmering of meaning encapsulated in the triangulation between Deanna’s, and our, ‘reclusiveness,’ ‘doll-ness,’ ‘farewell,’ and ‘nobody.’

We can only speculate on what identity-affirming role Durbin’s image on the wall in Het Achterhuis played for Anne Frank. Yet I feel encouraged to see it as slightly more than merely a signal of popular mainstream culture’s pin-ups penetrating the most secretive of girl’s rooms but instead – perhaps –something with somewhat of a personal significance, something that establishes an intimate and unlikely contact between the most public and the most private realms of understanding reality that form the core of a cult following, something predicated on a simmering of meaning encapsulated in the triangulation between Deanna’s, and our, ‘reclusiveness,’ ‘doll-ness,’ ‘farewell,’ and ‘nobody.’

Thank you so much for your post, I find this topic fascinating! It is interesting how fandom spurred the resurgence of Deanna’s star text in mainstream media after her death, and I wonder what that says about the function of cult fandoms. I am going to check out the Deanna Durbin Devotees, but I can only imagine that many members must not have been alive during the height of Deanna’s stardom, and so I am curious what you think her star text symbolizes for these fans? Thanks again!