Poetry by Radio: Paul Blackburn and WBAI

Post by Lisa Hollenbach

Post by Lisa Hollenbach

In the Special Collections reading room at UC-San Diego, I tune in to Pacifica station WBAI in New York City, circa the spring of 1961. Or, to put it more accurately, I listen to a copy of a tape made by the poet Paul Blackburn, which includes several WBAI broadcasts recorded that spring. Blackburn also produced his own poetry show on the station from 1964-65, and I’m here researching a project about poetry broadcasting on Pacifica Radio. Listening through the layers of mediation that stand in for Blackburn’s own listening ear, I catch an interview with Allen Ginsberg, a broadcast of Blackburn reading translations of medieval Provençal poetry, a Mozart piano concerto, and a BBC production of King Lear. At one point Blackburn reads directly into the tape recorder from Charles Olson’s Maximus Poems before the next recorded broadcast cuts in. During the Mozart, I can hear a typewriter in the background, and suddenly I’m placed in a room with dimensions. I wonder, though there’s no way to know, if he’s working on a poem.

In a recent post for this series, John McMurria asks, “Why Care About Radio Broadcast History in the On-Demand Digital Age?” As a literary scholar interested in radio broadcasting of poetry from the 1950s through the 1970s, this is a question I think about a lot. I often feel as though I’m working on several neglected cultural fronts at once, examining forms long declared dead, including during the period I study—poetry, radio, spoken word recording, the Pacifica Radio network itself. Yet the on-demand digital age is also reviving public interest and an experimental ethos to both recorded poetry performance and to radio’s digital afterlife. Preserving and narrating the cultural history of sound media history has repercussions for how we listen to the past and for creative possibility in the present.

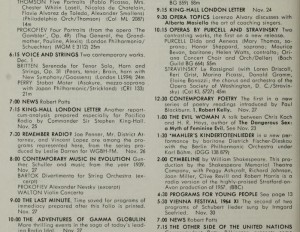

I hear echoes between our own digital moment and the 1960s, when the FM band became a site for experiments in underground and community radio, and when poets experimented with new poetic forms, new approaches to performance, and new media. The listener-sponsored Pacifica Radio network—first broadcasting from KPFA in Berkeley in 1949—was an influential innovator in the FM revolution. WBAI, acquired by Pacifica in 1960, quickly became a countercultural hub for freeform radio, minority perspectives, coverage of the Vietnam War and the antiwar movement, and innovative cultural programing. Poets’ voices and poetry were (and still are) heard constantly on Pacifica’s stations. In the sixties a WBAI listener might catch, for example, Ginsberg on Bob Fass’s Radio Unnameable, or a group reading and discussion by members of the Umbra Poets Workshop.

I hear echoes between our own digital moment and the 1960s, when the FM band became a site for experiments in underground and community radio, and when poets experimented with new poetic forms, new approaches to performance, and new media. The listener-sponsored Pacifica Radio network—first broadcasting from KPFA in Berkeley in 1949—was an influential innovator in the FM revolution. WBAI, acquired by Pacifica in 1960, quickly became a countercultural hub for freeform radio, minority perspectives, coverage of the Vietnam War and the antiwar movement, and innovative cultural programing. Poets’ voices and poetry were (and still are) heard constantly on Pacifica’s stations. In the sixties a WBAI listener might catch, for example, Ginsberg on Bob Fass’s Radio Unnameable, or a group reading and discussion by members of the Umbra Poets Workshop.

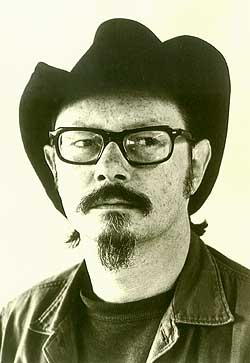

Paul Blackburn (a UW-Madison alumnus) was a fixture of Manhattan’s Lower East Side poetry scene until his early death from cancer in 1971. He co-curated two important reading series at the cafés Le Metro and Les Deux Mégots and helped to establish the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church. He also appeared several times on WBAI for interviews or to give readings before producing his own weekly Contemporary Poetry program. On his program, Blackburn occasionally invited poets into the studio, but he more often broadcast from his extensive tape collection. Blackburn recorded everything. His enormous portable tape recorder followed him to readings; it was also a fixture in his home, where he recorded late-night conversations with friends as well as the radio and his own poetry. A collection of Blackburn’s tapes, including recordings of his radio show, are now held with his papers at UCSD’s Archive for New Poetry.

Blackburn’s radio program often brought listeners to the cafés where poets like Ted Berrigan, Diane Wakoski, John Wieners, and Ed Sanders performed in front of lively, familiar audiences. In doing so, he introduced listeners both to a literary scene and to the importance of that scene to the poetry itself, as poets read works that named the very friends, cafés, and streets caught on the tapes. With casual introductions and a laissez-faire approach to sound editing, Blackburn projected a style and experimental aesthetic that fit well within WBAI’s overall freeform aesthetic at the time.

Blackburn’s stint as a radio producer was short-lived—an appearance by Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) pushed the station’s limits on obscenity too far—but his tapes also leave a fascinating record of radio listening. These include broadcasts from WBAI as well as other NY stations, documenting his daily life and poetic interests as well as nationally historic events, like John F. Kennedy’s state funeral. Blackburn probably recorded the radio for the same reasons we all used to—to capture for future listening or to share. But his radio listening also played a role in his compositional practice. One tape, for example, records a series of news broadcasts from December 1965 related to the launch and space flight of Gemini 7. Blackburn would draw on these for his poem “Newsclips 2,” which comically picks up on reports of the crew removing their space suits (“what a great idea, a pair / of astronauts / orbiting earth for two full weeks / in their underwear!”). The poet Robert Kelly states that Blackburn “collaborated with the tape recorder” to tune the page to voice and ear, but the voices indexed by his poetry include not only his own poetic voice but the highly mediated voices of radio—like the one that signs off “Newsclips 2”: “Don’t miss it boys and girls, and that’s / all for tonight.”

Blackburn’s stint as a radio producer was short-lived—an appearance by Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) pushed the station’s limits on obscenity too far—but his tapes also leave a fascinating record of radio listening. These include broadcasts from WBAI as well as other NY stations, documenting his daily life and poetic interests as well as nationally historic events, like John F. Kennedy’s state funeral. Blackburn probably recorded the radio for the same reasons we all used to—to capture for future listening or to share. But his radio listening also played a role in his compositional practice. One tape, for example, records a series of news broadcasts from December 1965 related to the launch and space flight of Gemini 7. Blackburn would draw on these for his poem “Newsclips 2,” which comically picks up on reports of the crew removing their space suits (“what a great idea, a pair / of astronauts / orbiting earth for two full weeks / in their underwear!”). The poet Robert Kelly states that Blackburn “collaborated with the tape recorder” to tune the page to voice and ear, but the voices indexed by his poetry include not only his own poetic voice but the highly mediated voices of radio—like the one that signs off “Newsclips 2”: “Don’t miss it boys and girls, and that’s / all for tonight.”

A relatively unknown poet’s brief stint as radio producer for a local noncommercial station is unlikely to make it into any major survey of broadcasting history. Yet I’m interested in Blackburn’s tape collection in part because it documents sonically not only a particular time and place, but how that moment was subjectively heard and engaged by artists. The Radio Preservation Task Force, by attending to “local, regional, noncommercial, and under represented movements in broadcasting history,” has the potential to direct us to unexpected places where radio history can be found, and the unexpected voices and sounds heard on American airwaves.

[…] Hollenbach is a literary scholar interested in poetry broadcasts from the 1950s to the 1970s. In her recent post for Antenna Blog‘s Radio Preservation Task Force series she describes her work as dealing with “several neglected cultural fronts at once, examining […]

[…] She wrote on her experience tuning into a WBAI recording in 1961, ” Listening through the layers of mediation that stand in for Blackburn’s own listening ear, I catch an interview with Allen Ginsberg, a broadcast of Blackburn reading translations of medieval Provençal poetry, a Mozart piano concerto, and a BBC production of King Lear. At one point Blackburn reads directly into the tape recorder from Charles Olson’s Maximus Poems before the next recorded broadcast cuts in. During the Mozart, I can hear a typewriter in the background, and suddenly I’m placed in a room with dimensions. I wonder, though there’s no way to know, if he’s working on a poem.” […]

When poetry was enjoying a real renaissance through readings at coffee houses, lofts and bars. Paul Blackburn brought his tape recorder to virtually every reading he attended (and he attended many) and could usually be found setting up chairs, adjusting the microphone and preparing an introduction for those readings which he organized. The series at Le Métro, Les Deux Magots, Dr. Generosity’s and St. Mark’s Church were all formed out of Blackburn’s generous enthusiasm, and his poetry show on WBAI radio brought the new writing out of the clubs and bars of the lower East Side and made it available to a wider audience. The tapes made of these readings constitute a virtual oral history of artistic activity during an exciting period in New York’s history, and some investigation of the contents of this collection will suggest a variety of scholarly and critical uses of the tapes